Having been seriously under the weather this week with wisdom tooth woes, I haven't been watching many movies, but I have been reading Stuart Kaminsky's Toby Peters mysteries. They're the perfect light reading for summer or sick days, especially for a classic movie fan.

If you aren't familiar with the series, here's an introduction. Toby Peters is a private detective in 1940s LA who specializes in tricky cases for Hollywood stars. While he doesn't claim to be the smartest guy in town, he is known for his ability to keep things under his hat, which makes him a perfect choice for publicity shy celebrities and their studio bosses. Toby has a thoroughly broken nose, a collection of unusual friends, and really rotten luck when it comes to being worked over by the bad guys. He gets occasional grief and assistance from his brother, Phil, a homicide cop, but usually he's trying to dodge the police because every corpse that turns up in his vicinity gets him picked up on suspicion of murder.

The first book, Bullet for a Star, features Errol Flynn, Peter Lorre, Edward G. Robinson, Humphrey Bogart, and a host of other stars. In other books, Toby takes cases for Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Judy Garland, and even Salvador Dali and Eleanor Roosevelt. Kaminsky really did his homework in capturing the personalities of these famous characters, and film fans will especially enjoy the way he works references to classic movies into the plots and dialogue.

Kaminsky died in 2009, but he left behind more than 60 novels. You'll find a lot of the Toby Peters books on Kindle at Amazon, so check them out there, or look for them at your local library!

Friday, August 30, 2013

Monday, August 26, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1944)

Plenty of the later Universal horror movies pack in the monsters, but House of Frankenstein (1944) really outdoes the rest by jamming a whole madhouse of familiar players into its many roles, not only as the headlining creatures but also as supporting characters. The story is so convoluted and episodic that it’s certainly not the chief attraction, but classic horror fans who know their stars will find the parade of performers entertaining in its own way, and Boris Karloff gets a particularly fun role as the devious and obsessive mad doctor whose adventures string together the appearances of Dracula, the Wolf Man, and Frankenstein’s monster. Directed by Erle C. Kenton, House of Frankenstein is by no means the best of the Universal horrors, but taken scene by scene and monster by monster it does provide some unique twists on the usual situations.

Karloff plays aspiring Frankenstein successor Dr. Niemann, who escapes from prison along with his hunchbacked assistant, Daniel (J. Carrol Naish). They hitch a ride from a traveling horror show and then murder its owner, Lampini (George Zucco), so that Niemann can assume his identity. Posing as the showman, Niemann resurrects Count Dracula (John Carradine) as an accomplice in his extensive revenge plot against the men who sent him to prison, but the vampire promptly becomes distracted by attractive female prey (Anne Gwynne). Later, in the ruins of Frankenstein’s castle, Niemann finds the Wolf Man (Lon Chaney, Jr.) and Frankenstein’s creature (Glenn Strange) frozen in ice and revives both of them, but he finds werewolf Larry Talbot harder to control than the other monsters. Daniel, meanwhile, becomes enamored of a pretty gypsy girl (Elena Verdugo) and grows jealous of her attention to Talbot.

While Karloff had originally gained fame playing the lumbering monster, he shows in this film that he can just as easily assume the role of the creator, and his Niemann is a fine example of the wild-eyed devotee of transgressive science. There are references to an earlier experiment in which Niemann transplanted a human brain into a dog, so from the start we know that he might actually be crazier than the original Frankenstein or any of his ill-fated heirs. More importantly, Niemann lies to and takes advantage of the dangerous supernatural beings he encounters; this is a man mad enough to play Dracula for a dupe and plot to make a science experiment out of the Wolf Man’s body and brain. He really only cares about Frankenstein’s creature; the rest of the monsters are just convenient means to his nefarious ends. Inevitably, Niemann’s duplicity catches up with him, but it’s ironically the lowly hunchback, tired of being played for a sucker, who raises the hand of vengeance against the scheming doctor.

The rest of the cast keep things interesting in spite of the disjointed plot. John Carradine has a brief but effective run as Count Dracula; his lean physique prefigures that of Christopher Lee even as he retains the aristocratic manners of Lugosi. Lon Chaney, Jr. makes his usual contribution as doomed Larry Talbot, this time with the added interest of a tragic love affair with the spirited gypsy girl. His role as part of a romantic triangle with the girl and the hunchback puts him into the odd position of playing Captain Phoebus in their version of the Victor Hugo tale, although Larry really does seem to return the gypsy’s affection. J. Carrol Naish proves one of the most inspired additions to the collection with his pathetic, jealous Daniel, who commits most of the murders in the film and yet still commands a degree of sympathy from the audience for his unrequited love. The victims and supporting characters are played by a who’s who of favorite actors, including George Zucco, Sig Ruman, Lionel Atwill, Frank Reicher, and Glenn Strange under all the makeup taking Karloff’s place as the creature.

Like most of the Universal monster pictures, House of Frankenstein kills off all of the creatures by the final scene, but House of Dracula (1945) brings them back to life for another round. For a different sort of horror from director Erle C. Kenton, try Island of Lost Souls (1932). Look for the many faces of Boris Karloff in The Mummy (1932), the Mr. Wong series, and Bedlam (1946). Lon Chaney, Jr. plays the Wolf Man in several Universal films, beginning with The Wolf Man (1941). Versatile character actor J. Carrol Naish turns up in more than 200 film and television roles, but he earned Oscar nominations for Best Supporting Actor in Sahara (1943) and A Medal for Benny (1945). He’s hard to recognize under the makeup and feathers, but you’ll also find him playing Chief Sitting Bull in Annie Get Your Gun (1950).

Karloff plays aspiring Frankenstein successor Dr. Niemann, who escapes from prison along with his hunchbacked assistant, Daniel (J. Carrol Naish). They hitch a ride from a traveling horror show and then murder its owner, Lampini (George Zucco), so that Niemann can assume his identity. Posing as the showman, Niemann resurrects Count Dracula (John Carradine) as an accomplice in his extensive revenge plot against the men who sent him to prison, but the vampire promptly becomes distracted by attractive female prey (Anne Gwynne). Later, in the ruins of Frankenstein’s castle, Niemann finds the Wolf Man (Lon Chaney, Jr.) and Frankenstein’s creature (Glenn Strange) frozen in ice and revives both of them, but he finds werewolf Larry Talbot harder to control than the other monsters. Daniel, meanwhile, becomes enamored of a pretty gypsy girl (Elena Verdugo) and grows jealous of her attention to Talbot.

While Karloff had originally gained fame playing the lumbering monster, he shows in this film that he can just as easily assume the role of the creator, and his Niemann is a fine example of the wild-eyed devotee of transgressive science. There are references to an earlier experiment in which Niemann transplanted a human brain into a dog, so from the start we know that he might actually be crazier than the original Frankenstein or any of his ill-fated heirs. More importantly, Niemann lies to and takes advantage of the dangerous supernatural beings he encounters; this is a man mad enough to play Dracula for a dupe and plot to make a science experiment out of the Wolf Man’s body and brain. He really only cares about Frankenstein’s creature; the rest of the monsters are just convenient means to his nefarious ends. Inevitably, Niemann’s duplicity catches up with him, but it’s ironically the lowly hunchback, tired of being played for a sucker, who raises the hand of vengeance against the scheming doctor.

The rest of the cast keep things interesting in spite of the disjointed plot. John Carradine has a brief but effective run as Count Dracula; his lean physique prefigures that of Christopher Lee even as he retains the aristocratic manners of Lugosi. Lon Chaney, Jr. makes his usual contribution as doomed Larry Talbot, this time with the added interest of a tragic love affair with the spirited gypsy girl. His role as part of a romantic triangle with the girl and the hunchback puts him into the odd position of playing Captain Phoebus in their version of the Victor Hugo tale, although Larry really does seem to return the gypsy’s affection. J. Carrol Naish proves one of the most inspired additions to the collection with his pathetic, jealous Daniel, who commits most of the murders in the film and yet still commands a degree of sympathy from the audience for his unrequited love. The victims and supporting characters are played by a who’s who of favorite actors, including George Zucco, Sig Ruman, Lionel Atwill, Frank Reicher, and Glenn Strange under all the makeup taking Karloff’s place as the creature.

Like most of the Universal monster pictures, House of Frankenstein kills off all of the creatures by the final scene, but House of Dracula (1945) brings them back to life for another round. For a different sort of horror from director Erle C. Kenton, try Island of Lost Souls (1932). Look for the many faces of Boris Karloff in The Mummy (1932), the Mr. Wong series, and Bedlam (1946). Lon Chaney, Jr. plays the Wolf Man in several Universal films, beginning with The Wolf Man (1941). Versatile character actor J. Carrol Naish turns up in more than 200 film and television roles, but he earned Oscar nominations for Best Supporting Actor in Sahara (1943) and A Medal for Benny (1945). He’s hard to recognize under the makeup and feathers, but you’ll also find him playing Chief Sitting Bull in Annie Get Your Gun (1950).

Sunday, August 25, 2013

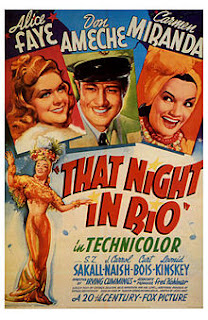

Classic Films in Focus: THAT NIGHT IN RIO (1941)

Don Ameche fans can get a double dose of the charismatic leading man in That Night in Rio (1941), a frothy musical romance costarring Alice Faye and Carmen Miranda. Directed by Irving Cummings, this South American story features Ameche playing not one but two characters, which drives a complicated plot of romantic substitutions and mistaken identity. Technicolor splendor enhances its lively musical numbers, and the supporting cast includes familiar character actors S.Z. Sakall, J. Carrol Naish, and Leonid Kinskey. Like many of the Fox musicals of the wartime era, That Night in Rio is a fun escape from the seriousness of real life, light on substance but rich with music and glorious color.

Ameche stars in a dual role as American entertainer Larry Martin and aristocratic ladies’ man Baron Duarte. When the baron lands in financial trouble and leaves town, his anxious colleagues hire Larry to impersonate him, but Larry uses the opportunity to flirt with the beautiful baroness, Cecilia (Alice Faye). Meanwhile, Larry’s jealous girlfriend, Carmen (Carmen Miranda), turns up at the baron’s estate and recognizes Larry in disguise. When the real baron returns, he and Larry take turns pretending to be one another, much to the confusion of the baroness.

With its jealous lovers and character doubles, That Night in Rio has something of the air of a Shakespearean forest romance, although it was actually adapted from a play called The Red Cat. Ameche certainly seems to be enjoying himself in both roles, and he’s particularly debonair as the Baron, replete with monocle and distinguished, silver-streaked hair. The set-up ensures that Ameche will get both girls by the film’s end, no matter how the pairings sort themselves out, or perhaps it ensures that each girl will get an Ameche, since the two women are pretty aggressive - if sometimes surreptitiously so - in pursuing their partners. Alice Faye and Carmen Miranda make good foils to one another; Faye’s cool blonde look and deep, dreamy voice contrast perfectly with Miranda’s hot Latin energy, and each has plenty of opportunity to shine in musical numbers. Miranda, however, definitely wins in the spectacle contest; few performers were ever more perfectly formed for Technicolor, and Miranda’s wild outfits and oversized personality practically leap off the screen during her songs.

The identical protagonists provide That Night in Rio with an excuse for lively visual hijinks to go along with its music and romance. When Larry and Baron Duarte appear together, the film indulges in fun effects shots that still look very convincing some 70 years later, although a few scenes are clearly using a stand-in actor for the character not facing the camera. One gag involves the baron, Larry, and a very confused J. Carrol Naish with a dressing screen around which the two men swap places. Reacting to the ongoing confusion are the very funny S.Z. Sakall and Curt Bois as the baron’s nervous associates, who get a lot more than they bargained for when they employ Larry’s unique services. Leonid Kinskey, whom viewers will recognize as Sascha in Casablanca (1942), appears as Pierre, an amorous Frenchman who hopes in vain to impress the baroness as a potential lover.

The Red Cat was also adapted by Hollywood as the 1951 film, On the Riviera, starring Danny Kaye in the double lead. For more of Don Ameche and Alice Faye, see In Old Chicago (1937), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938), and Lillian Russell (1940). Faye and Carmen Miranda both appear in Weekend in Havana (1941), The Gang’s All Here (1943), and Four Jills in a Jeep (1944). Irving Cummings also directed Ameche and Miranda in Down Argentine Way (1940); for more of his work, see the Shirley Temple films Curly Top (1935) and Little Miss Broadway (1938) or yet another Faye and Ameche picture, Hollywood Cavalcade (1939). Look for various combinations of the director and the three stars with other usual suspects like Betty Grable and Tyrone Power.

Ameche stars in a dual role as American entertainer Larry Martin and aristocratic ladies’ man Baron Duarte. When the baron lands in financial trouble and leaves town, his anxious colleagues hire Larry to impersonate him, but Larry uses the opportunity to flirt with the beautiful baroness, Cecilia (Alice Faye). Meanwhile, Larry’s jealous girlfriend, Carmen (Carmen Miranda), turns up at the baron’s estate and recognizes Larry in disguise. When the real baron returns, he and Larry take turns pretending to be one another, much to the confusion of the baroness.

With its jealous lovers and character doubles, That Night in Rio has something of the air of a Shakespearean forest romance, although it was actually adapted from a play called The Red Cat. Ameche certainly seems to be enjoying himself in both roles, and he’s particularly debonair as the Baron, replete with monocle and distinguished, silver-streaked hair. The set-up ensures that Ameche will get both girls by the film’s end, no matter how the pairings sort themselves out, or perhaps it ensures that each girl will get an Ameche, since the two women are pretty aggressive - if sometimes surreptitiously so - in pursuing their partners. Alice Faye and Carmen Miranda make good foils to one another; Faye’s cool blonde look and deep, dreamy voice contrast perfectly with Miranda’s hot Latin energy, and each has plenty of opportunity to shine in musical numbers. Miranda, however, definitely wins in the spectacle contest; few performers were ever more perfectly formed for Technicolor, and Miranda’s wild outfits and oversized personality practically leap off the screen during her songs.

The identical protagonists provide That Night in Rio with an excuse for lively visual hijinks to go along with its music and romance. When Larry and Baron Duarte appear together, the film indulges in fun effects shots that still look very convincing some 70 years later, although a few scenes are clearly using a stand-in actor for the character not facing the camera. One gag involves the baron, Larry, and a very confused J. Carrol Naish with a dressing screen around which the two men swap places. Reacting to the ongoing confusion are the very funny S.Z. Sakall and Curt Bois as the baron’s nervous associates, who get a lot more than they bargained for when they employ Larry’s unique services. Leonid Kinskey, whom viewers will recognize as Sascha in Casablanca (1942), appears as Pierre, an amorous Frenchman who hopes in vain to impress the baroness as a potential lover.

The Red Cat was also adapted by Hollywood as the 1951 film, On the Riviera, starring Danny Kaye in the double lead. For more of Don Ameche and Alice Faye, see In Old Chicago (1937), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938), and Lillian Russell (1940). Faye and Carmen Miranda both appear in Weekend in Havana (1941), The Gang’s All Here (1943), and Four Jills in a Jeep (1944). Irving Cummings also directed Ameche and Miranda in Down Argentine Way (1940); for more of his work, see the Shirley Temple films Curly Top (1935) and Little Miss Broadway (1938) or yet another Faye and Ameche picture, Hollywood Cavalcade (1939). Look for various combinations of the director and the three stars with other usual suspects like Betty Grable and Tyrone Power.

Friday, August 23, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: WAGON MASTER (1950)

John Ford directed many more famous Westerns than Wagon Master (1950), but this modest oater about a Mormon wagon train reveals many of Ford’s signature touches and favorite players. It’s a dramatic tale that focuses on the interactions of several different kinds of frontier outsiders, including the Mormon settlers, their drifter guides, a small cadre of show people, and a dangerous gang of outlaws. Accompanied by the distinctive sounds of The Sons of the Pioneers, Wagon Master offers taut drama as well as the iconic scenery one expects from Ford’s films. Western fans will also appreciate the performances of genre stalwarts like Ben Johnson, Harry Carey, Jr., Ward Bond, Joanne Dru, Jane Darwell, and even a young James Arness.

Ben Johnson and Harry Carey, Jr. star as Travis and Sandy, a pair of wandering horse traders who take on a job as wagon masters for a group of Mormon settlers crossing a dangerous wilderness. The Mormons are led by Elder Wiggs (Ward Bond), who sees the young men’s presence as a gift from God, even if they cause some conflict within the religious group. The wagon train takes on a trio of stranded snake oil peddlars, including the attractive Denver (Joanne Dru), but they are then joined by a band of outlaws led by the injured Uncle Shiloh Clegg (Charles Kemper), who uses the settlers to hide from the law. Forbidding terrain and encounters with Native Americans add to the obstacles that the group must face on their long journey, but the Cleggs within their midst present the worst and most constant danger.

Wagon Master is not a flashy showpiece picture; it depends more on an ensemble cast of characters than a single, dominating personality. Each group, however, has its central figure: Ward Bond is gruff but good-natured as the Mormon Elder, Joanne Dru is saucy and charming as the worldly Denver, and Charles Kemper hides his menace beneath a folksy veneer as Uncle Shiloh. Ben Johnson’s Travis acts as the force that binds them, but the actor wisely plays the role with a frank, casual air that befits his cowboy persona. Harry Carey, Jr. makes an excellent partner to Johnson’s understated hero as a younger and more eager character who rapidly falls for one of the Mormon maidens. Jane Darwell, always an impressive presence, doesn’t have as much to do as one might hope, but James Arness gets a memorable opportunity to play the villain as one of the murderous Cleggs. Alan Mowbray has a small but noteworthy role as the medicine show leader, and Ruth Clifford is faded but kindly as his companion, Miss Fleuretty. These more colorful characters attract the viewer’s attention more than the mass of Mormons who make up most of the train, although Russell Simpson and Kathleen O’Malley get a few good scenes as Adam and his pretty daughter, Prudence.

Like Westward the Women (1951), this wagon train story doesn’t shy away from depicting the hazards of frontier settlement, and there are tense encounters with the natives as well as some dramatic moments of wagons in peril. The representation of the Mormon pioneers is unfailingly sympathetic, although polygamy is really only winked at when one settler’s wives look on dourly as he dances with a Navajo woman. Like the Quakers in other Westerns, the Mormons are shown as deeply religious people who oppose violence and immoral behavior but do not attempt to force others to live by their beliefs. We do see the settlers being run out of town early in the film, reminding us that they, like the rest of our characters, are treated as undesirables, but the Mormons are the opposite of the Cleggs in every way that matters.

With its unassuming hero and prominent musical accompaniment, Wagon Master has more in common with the popular “B” Westerns of its era than it does with Ford’s most lauded genre efforts, but it’s still an excellent picture. For contrast with the director’s other Westerns, see Stagecoach (1939), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Catch Ben Johnson in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Shane (1953), and The Wild Bunch (1969). Harry Carey, Jr., whose father was also a veteran Western star, has good roles in 3 Godfathers (1948), The Searchers, and The Whales of August (1987). Ward Bond, Joanne Dru, and Jane Darwell all turn up in other Ford films, and Darwell even won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role in The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

Wagon Master is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant. The film inspired the popular television series, Wagon Train, and you'll find several of the original movie's stars in various episodes.

Ben Johnson and Harry Carey, Jr. star as Travis and Sandy, a pair of wandering horse traders who take on a job as wagon masters for a group of Mormon settlers crossing a dangerous wilderness. The Mormons are led by Elder Wiggs (Ward Bond), who sees the young men’s presence as a gift from God, even if they cause some conflict within the religious group. The wagon train takes on a trio of stranded snake oil peddlars, including the attractive Denver (Joanne Dru), but they are then joined by a band of outlaws led by the injured Uncle Shiloh Clegg (Charles Kemper), who uses the settlers to hide from the law. Forbidding terrain and encounters with Native Americans add to the obstacles that the group must face on their long journey, but the Cleggs within their midst present the worst and most constant danger.

Wagon Master is not a flashy showpiece picture; it depends more on an ensemble cast of characters than a single, dominating personality. Each group, however, has its central figure: Ward Bond is gruff but good-natured as the Mormon Elder, Joanne Dru is saucy and charming as the worldly Denver, and Charles Kemper hides his menace beneath a folksy veneer as Uncle Shiloh. Ben Johnson’s Travis acts as the force that binds them, but the actor wisely plays the role with a frank, casual air that befits his cowboy persona. Harry Carey, Jr. makes an excellent partner to Johnson’s understated hero as a younger and more eager character who rapidly falls for one of the Mormon maidens. Jane Darwell, always an impressive presence, doesn’t have as much to do as one might hope, but James Arness gets a memorable opportunity to play the villain as one of the murderous Cleggs. Alan Mowbray has a small but noteworthy role as the medicine show leader, and Ruth Clifford is faded but kindly as his companion, Miss Fleuretty. These more colorful characters attract the viewer’s attention more than the mass of Mormons who make up most of the train, although Russell Simpson and Kathleen O’Malley get a few good scenes as Adam and his pretty daughter, Prudence.

Like Westward the Women (1951), this wagon train story doesn’t shy away from depicting the hazards of frontier settlement, and there are tense encounters with the natives as well as some dramatic moments of wagons in peril. The representation of the Mormon pioneers is unfailingly sympathetic, although polygamy is really only winked at when one settler’s wives look on dourly as he dances with a Navajo woman. Like the Quakers in other Westerns, the Mormons are shown as deeply religious people who oppose violence and immoral behavior but do not attempt to force others to live by their beliefs. We do see the settlers being run out of town early in the film, reminding us that they, like the rest of our characters, are treated as undesirables, but the Mormons are the opposite of the Cleggs in every way that matters.

With its unassuming hero and prominent musical accompaniment, Wagon Master has more in common with the popular “B” Westerns of its era than it does with Ford’s most lauded genre efforts, but it’s still an excellent picture. For contrast with the director’s other Westerns, see Stagecoach (1939), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Catch Ben Johnson in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Shane (1953), and The Wild Bunch (1969). Harry Carey, Jr., whose father was also a veteran Western star, has good roles in 3 Godfathers (1948), The Searchers, and The Whales of August (1987). Ward Bond, Joanne Dru, and Jane Darwell all turn up in other Ford films, and Darwell even won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role in The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

Wagon Master is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant. The film inspired the popular television series, Wagon Train, and you'll find several of the original movie's stars in various episodes.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: DANGEROUS WHEN WET (1953)

Musical comedies tend to be light, colorful affairs, the cinematic equivalent of cotton candy, and they have to be judged accordingly. If the picture is fun, sweet, and easy to watch, then it succeeds at its intended purpose, and Dangerous When Wet (1953) certainly fits the bill. Yes, Esther Williams is a bit of a gimmick star, a sort of aquatic Doris Day, but she has plenty of personality even when she isn’t in the water, and this particular Williams film gets a boost from a memorable supporting cast that includes Jack Carson, Fernando Lamas, William Demarest, Charlotte Greenwood, and Denise Darcel. With veteran musical director Charles Walters at the helm, Dangerous When Wet provides a fast-moving story, some unexpected twists, and a peppy energy that will keep the whole family entertained.

Williams plays Arkansas farm girl Katie Higgins, the oldest daughter in a family of fitness buffs. When tonic salesman Windy (Jack Carson) arrives in town, he convinces the Higgins clan to represent his product and enter a competition to swim the English Channel. Windy and the Higgins family travel to England and then France to prepare for the contest, but Katie becomes distracted from the race by a suave Frenchman (Fernando Lamas), while a sexy French swimmer (Denise Darcel) sets her swim cap at Windy.

In films with Doris Day and other leading ladies, Jack Carson often plays an unlikely love interest; sometimes he gets the girl and sometimes he doesn’t. Dangerous When Wet works hard to keep us in suspense about its various amours, with Windy clearly interested in Katie but then sideswiped by the more aggressive French characters. We can’t blame Windy for being attracted to Katie; her first scenes in the film amply display Williams’ robust physical charms. Fernando Lamas’ rival admirer initially comes off as something of a wolf, so we don’t know whether to root for Carson’s snake oil American or Lamas’ champagne seducer. Does Katie end up with the right guy? The movie makes us wait to find out, and I won’t spoil the ending by telling you here.

The supporting players are great fun. Crabby William Demarest and lanky Charlotte Greenwood make credible health nuts as the Higgins parents, and both are sublimely gifted physical comedians who are justly beloved by classic movie fans. Barbara Whiting provides most of the musical numbers as Katie’s younger sister, Suzie, although the family anthem is a ridiculously perky tune that gets repeated several times throughout the film. Denise Darcel puts her French accent to good use as Gigi, a rival swimmer who befriends Katie and pursues Windy with boundless joie de vivre. Stealing the picture from the human stars are cartoon icons Tom and Jerry, who appear in an underwater dream sequence with Esther Williams and an amorous octopus standing in for Fernando Lamas. Kids will enjoy the rest of the movie, but the animated sequence is a definitely a highlight that younger viewers are sure to love.

Dangerous When Wet might not be one of the greatest Hollywood musicals ever made, but it’s perfectly entertaining, and those interested in Esther Williams will find it a charming example of her signature style. For more of the swimming star, try Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1949), Neptune’s Daughter (1949), and Million Dollar Mermaid (1952). Look for Jack Carson playing similar roles opposite Doris Day in Romance on the High Seas (1948), My Dream is Yours (1949), and It’s a Great Feeling (1949). Fernando Lamas also stars in The Merry Widow (1952), Sangaree (1953), and The Lost World (1960); after three unsuccessful marriages, he married Esther Williams in real life in 1969 and remained with her until his death in 1982. Catch William Demarest playing more dads in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) and Viva Las Vegas (1964), and see Charlotte Greenwood in Down Argentine Way (1940) and Oklahoma! (1955). Denise Darcel has memorable roles in Westward the Women (1951) and Vera Cruz (1954). For more from director Charles Walters, try Easter Parade (1948), Summer Stock (1950), and The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964).

Dangerous When Wet is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Williams plays Arkansas farm girl Katie Higgins, the oldest daughter in a family of fitness buffs. When tonic salesman Windy (Jack Carson) arrives in town, he convinces the Higgins clan to represent his product and enter a competition to swim the English Channel. Windy and the Higgins family travel to England and then France to prepare for the contest, but Katie becomes distracted from the race by a suave Frenchman (Fernando Lamas), while a sexy French swimmer (Denise Darcel) sets her swim cap at Windy.

In films with Doris Day and other leading ladies, Jack Carson often plays an unlikely love interest; sometimes he gets the girl and sometimes he doesn’t. Dangerous When Wet works hard to keep us in suspense about its various amours, with Windy clearly interested in Katie but then sideswiped by the more aggressive French characters. We can’t blame Windy for being attracted to Katie; her first scenes in the film amply display Williams’ robust physical charms. Fernando Lamas’ rival admirer initially comes off as something of a wolf, so we don’t know whether to root for Carson’s snake oil American or Lamas’ champagne seducer. Does Katie end up with the right guy? The movie makes us wait to find out, and I won’t spoil the ending by telling you here.

The supporting players are great fun. Crabby William Demarest and lanky Charlotte Greenwood make credible health nuts as the Higgins parents, and both are sublimely gifted physical comedians who are justly beloved by classic movie fans. Barbara Whiting provides most of the musical numbers as Katie’s younger sister, Suzie, although the family anthem is a ridiculously perky tune that gets repeated several times throughout the film. Denise Darcel puts her French accent to good use as Gigi, a rival swimmer who befriends Katie and pursues Windy with boundless joie de vivre. Stealing the picture from the human stars are cartoon icons Tom and Jerry, who appear in an underwater dream sequence with Esther Williams and an amorous octopus standing in for Fernando Lamas. Kids will enjoy the rest of the movie, but the animated sequence is a definitely a highlight that younger viewers are sure to love.

Dangerous When Wet might not be one of the greatest Hollywood musicals ever made, but it’s perfectly entertaining, and those interested in Esther Williams will find it a charming example of her signature style. For more of the swimming star, try Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1949), Neptune’s Daughter (1949), and Million Dollar Mermaid (1952). Look for Jack Carson playing similar roles opposite Doris Day in Romance on the High Seas (1948), My Dream is Yours (1949), and It’s a Great Feeling (1949). Fernando Lamas also stars in The Merry Widow (1952), Sangaree (1953), and The Lost World (1960); after three unsuccessful marriages, he married Esther Williams in real life in 1969 and remained with her until his death in 1982. Catch William Demarest playing more dads in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) and Viva Las Vegas (1964), and see Charlotte Greenwood in Down Argentine Way (1940) and Oklahoma! (1955). Denise Darcel has memorable roles in Westward the Women (1951) and Vera Cruz (1954). For more from director Charles Walters, try Easter Parade (1948), Summer Stock (1950), and The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964).

Dangerous When Wet is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: THE MUMMY (1959)

Having already made The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958), Hammer Films next turned its attention to reinventing the story of a different horror icon, the stiff-armed Egyptian creature known as The Mummy (1959). This adaptation, like the best of the Hammer horrors, stars Peter Cushing as the human protagonist and Christopher Lee as the monster, and it also benefits from the effective direction of Terence Fisher. Lavish, classy, and inventive in its take on the oft-told tale, The Mummy adds a hint of signature Hammer sex appeal to its story of undying love between an Ancient Egyptian princess and her devoted high priest.

Peter Cushing stars as British archaeologist John Banning, who discovers the tomb of the Princess Ananka along with his father (Felix Aylmer). As soon as they open the sacred grave, however, the Bannings begin to suffer ill fortune, beginning with John’s father, who goes mad after an encounter with Kharis (Christopher Lee), the living mummy who guards the tomb. Several years later, in England, Kharis and his keeper, Mehemet Bey (George Pastell), exact their revenge on the men who desecrated Ananka’s resting place, but the mummy is also attracted to Banning’s wife, Isobel (Yvonne Furneaux), who happens to look exactly like his long lost love.

The Egyptian story offers another rich opportunity for the combined talents of Cushing and Lee, with characters who follow the same general outlines as their earlier roles but still evoke unique interpretations from each performer. Cushing gets almost all of the dialogue as the intellectual but mild-mannered Banning, whose physical fragility is emphasized by a twisted leg. He’s a gentle family man, devoted to his father and his wife, and his inability to enter the tomb at the beginning of the film underlines our sense of him as one who has not deserved the grisly fate pronounced by the ancient gods. Lee, who speaks only briefly in a flashback scene, brings his tremendous bodily presence into play as the imposing mummy, but his eyes are even more effective. With them he conveys Kharis’ determination, his suffering, and his immortal devotion to Ananka. The impressive makeup adds to Lee’s overall impact on the viewer; he looks ancient and terrible without seeming too much like a guy wrapped up in bulky bandages, and the detail of his sealed mouth gives him an especially tragic air. Watch Kharis when he first sees Isobel and recognizes in her the image of his beloved princess; no other mummy has ever looked more physically dead and yet emotionally alive, the victim of a wounded heart that might have ceased beating but is still quite capable of breaking.

George Pastell, a Greek, gives a subtle performance as the modern day disciple of the ancient Egyptian god. He’s exotic without being cartoonish, and he makes a formidable opponent as the director of the mummy’s actions. Yvonne Furneaux, as both Isobel and Ananka, doesn’t have that much to do, but she looks terrific, and it’s easy to see why both Banning and the mummy fall in love with her, especially when she lets her hair down. We do get a few tantalizing glimpses of her naked flesh in the flashback scenes, although they’re pretty tame by Hammer standards. The rest of the supporting players are solid, as well, although there might be a touch too much emphasis on the boozy locals who react to the mummy’s appearances about the countryside.

For more Hammer classics from Cushing, Lee, and director Terence Fisher, see The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Horror of Dracula (1958), and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959). You’ll also find Cushing and Lee teaming up in other horror films, including I, Monster (1971), Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972), and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973); don’t miss their final collaboration in the wry horror-comedy, House of the Long Shadows (1983). Yvonne Furneaux also appears in La Dolce Vita (1960), The Lion of Thebes (1964), and Repulsion (1965). If mummy stories tickle your fancy, try The Mummy (1932), The Mummy’s Hand (1940), and The Mummy’s Tomb (1942) for more classics, or see more recent incarnations in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (1990), The Mummy (1999), and the cult horror-comedy, Bubba Ho-Tep (2002).

Peter Cushing stars as British archaeologist John Banning, who discovers the tomb of the Princess Ananka along with his father (Felix Aylmer). As soon as they open the sacred grave, however, the Bannings begin to suffer ill fortune, beginning with John’s father, who goes mad after an encounter with Kharis (Christopher Lee), the living mummy who guards the tomb. Several years later, in England, Kharis and his keeper, Mehemet Bey (George Pastell), exact their revenge on the men who desecrated Ananka’s resting place, but the mummy is also attracted to Banning’s wife, Isobel (Yvonne Furneaux), who happens to look exactly like his long lost love.

The Egyptian story offers another rich opportunity for the combined talents of Cushing and Lee, with characters who follow the same general outlines as their earlier roles but still evoke unique interpretations from each performer. Cushing gets almost all of the dialogue as the intellectual but mild-mannered Banning, whose physical fragility is emphasized by a twisted leg. He’s a gentle family man, devoted to his father and his wife, and his inability to enter the tomb at the beginning of the film underlines our sense of him as one who has not deserved the grisly fate pronounced by the ancient gods. Lee, who speaks only briefly in a flashback scene, brings his tremendous bodily presence into play as the imposing mummy, but his eyes are even more effective. With them he conveys Kharis’ determination, his suffering, and his immortal devotion to Ananka. The impressive makeup adds to Lee’s overall impact on the viewer; he looks ancient and terrible without seeming too much like a guy wrapped up in bulky bandages, and the detail of his sealed mouth gives him an especially tragic air. Watch Kharis when he first sees Isobel and recognizes in her the image of his beloved princess; no other mummy has ever looked more physically dead and yet emotionally alive, the victim of a wounded heart that might have ceased beating but is still quite capable of breaking.

George Pastell, a Greek, gives a subtle performance as the modern day disciple of the ancient Egyptian god. He’s exotic without being cartoonish, and he makes a formidable opponent as the director of the mummy’s actions. Yvonne Furneaux, as both Isobel and Ananka, doesn’t have that much to do, but she looks terrific, and it’s easy to see why both Banning and the mummy fall in love with her, especially when she lets her hair down. We do get a few tantalizing glimpses of her naked flesh in the flashback scenes, although they’re pretty tame by Hammer standards. The rest of the supporting players are solid, as well, although there might be a touch too much emphasis on the boozy locals who react to the mummy’s appearances about the countryside.

For more Hammer classics from Cushing, Lee, and director Terence Fisher, see The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Horror of Dracula (1958), and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959). You’ll also find Cushing and Lee teaming up in other horror films, including I, Monster (1971), Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972), and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973); don’t miss their final collaboration in the wry horror-comedy, House of the Long Shadows (1983). Yvonne Furneaux also appears in La Dolce Vita (1960), The Lion of Thebes (1964), and Repulsion (1965). If mummy stories tickle your fancy, try The Mummy (1932), The Mummy’s Hand (1940), and The Mummy’s Tomb (1942) for more classics, or see more recent incarnations in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (1990), The Mummy (1999), and the cult horror-comedy, Bubba Ho-Tep (2002).

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: SON OF DRACULA (1943)

Lon Chaney, Jr., God bless him, had certain talents as an actor, but he was no man of a thousand faces like his chameleon father. The limits of the younger Chaney’s abilities come into plain view in Son of Dracula (1943), which badly miscasts the horror star as the iconic vampire (or his descendant, it’s never quite clear). Directed by Robert Siodmak and costarring Robert Paige, Louise Allbritton, and Evelyn Ankers, Son of Dracula never really takes off, although it does tempt the audience with its story of a morbid anti-heroine and increasingly unhinged hero.

Arriving under the pseudonym of Count Alucard, Chaney plays a vampire drawn to the swamps of the Southern United States by Kay Caldwell (Louise Allbritton), a lovely young woman with an unhealthy interest in the occult. Alucard promptly kills Kay’s elderly father, and Kay inherits the Gothic mansion where she and Alucard intend to take up their undead residence. Kay’s longtime boyfriend, Frank (Robert Paige), is horrified by her fascination with the count, and her sister, Claire (Evelyn Ankers), doesn’t know what to make of Frank’s wild-eyed reports that Kay has become an immortal monster. Only kindly Dr. Brewster (Frank Craven) and vampire expert Professor Lazlo (J. Edward Bromberg) suspect that Frank’s ravings really contain the truth about Alucard and his morbid bride.

Chaney is best remembered today for his performances as werewolf Larry Talbot, first in The Wolf Man (1941) and then in a number of sequels. As a tragic everyman, Talbot perfectly suits Chaney’s middle-class look and earnest demeanor, but Dracula is a completely different type. He embodies Old World privilege, seductive foreign influence, and dangerous sex appeal, none of which are conveyed by Chaney’s version of the character. His bulky, solid Alucard looks more likely to drink beer than blood, and his flat American accent makes his dialogue patently ridiculous. Chaney would play werewolves, mummies, and a variety of strange characters over the course of his career, but Son of Dracula would be his only attempt at a vampire role, and that’s probably for the best.

Chaney’s inadequacy as the title character dooms the film as a whole, but the plot revolving around Frank and Kay still offers some entertainment for the hardcore horror fan. Louise Allbritton has something of a Cat People look going on for Kay, and we know she’s a strange girl when we first see her trailing her Gothic dress into the swamp to visit her old gypsy adviser. Even before she becomes a vampire she looks like one, with her dark hair, gossamer gowns, and moonstruck air. Robert Paige has the role with the most meat on it as the increasingly unhinged Frank; he’s equal parts Renfield and Harker, especially when the undead Kay turns up in his jail cell after he has confessed to accidentally killing her. The doomed love story between Frank and Kay makes the end of the picture one of its strongest scenes, one in which Chaney’s ineffective vampire does not figure at all.

Be sure to notice Hattie McDaniel’s sister, Etta, in a small role as Dr. Brewster’s housekeeper, Sarah. Robert Siodmak went on to direct a number of well-regarded films, including The Spiral Staircase (1945), The Killers (1946), and Criss Cross (1949). For contrast, see Lon Chaney, Jr. in serious dramatic roles in Of Mice and Men (1939) and High Noon (1952). You’ll find Louise Allbritton in The Egg and I (1947), while Evelyn Ankers plays Larry Talbot’s love interest in The Wolf Man (1941) and Elsa Frankenstein in The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942). For more of Robert Paige, try Blonde Ice (1948), Abbott and Costello Go to Mars (1953), or Bye Bye Birdie (1963).

Arriving under the pseudonym of Count Alucard, Chaney plays a vampire drawn to the swamps of the Southern United States by Kay Caldwell (Louise Allbritton), a lovely young woman with an unhealthy interest in the occult. Alucard promptly kills Kay’s elderly father, and Kay inherits the Gothic mansion where she and Alucard intend to take up their undead residence. Kay’s longtime boyfriend, Frank (Robert Paige), is horrified by her fascination with the count, and her sister, Claire (Evelyn Ankers), doesn’t know what to make of Frank’s wild-eyed reports that Kay has become an immortal monster. Only kindly Dr. Brewster (Frank Craven) and vampire expert Professor Lazlo (J. Edward Bromberg) suspect that Frank’s ravings really contain the truth about Alucard and his morbid bride.

Chaney is best remembered today for his performances as werewolf Larry Talbot, first in The Wolf Man (1941) and then in a number of sequels. As a tragic everyman, Talbot perfectly suits Chaney’s middle-class look and earnest demeanor, but Dracula is a completely different type. He embodies Old World privilege, seductive foreign influence, and dangerous sex appeal, none of which are conveyed by Chaney’s version of the character. His bulky, solid Alucard looks more likely to drink beer than blood, and his flat American accent makes his dialogue patently ridiculous. Chaney would play werewolves, mummies, and a variety of strange characters over the course of his career, but Son of Dracula would be his only attempt at a vampire role, and that’s probably for the best.

Chaney’s inadequacy as the title character dooms the film as a whole, but the plot revolving around Frank and Kay still offers some entertainment for the hardcore horror fan. Louise Allbritton has something of a Cat People look going on for Kay, and we know she’s a strange girl when we first see her trailing her Gothic dress into the swamp to visit her old gypsy adviser. Even before she becomes a vampire she looks like one, with her dark hair, gossamer gowns, and moonstruck air. Robert Paige has the role with the most meat on it as the increasingly unhinged Frank; he’s equal parts Renfield and Harker, especially when the undead Kay turns up in his jail cell after he has confessed to accidentally killing her. The doomed love story between Frank and Kay makes the end of the picture one of its strongest scenes, one in which Chaney’s ineffective vampire does not figure at all.

Be sure to notice Hattie McDaniel’s sister, Etta, in a small role as Dr. Brewster’s housekeeper, Sarah. Robert Siodmak went on to direct a number of well-regarded films, including The Spiral Staircase (1945), The Killers (1946), and Criss Cross (1949). For contrast, see Lon Chaney, Jr. in serious dramatic roles in Of Mice and Men (1939) and High Noon (1952). You’ll find Louise Allbritton in The Egg and I (1947), while Evelyn Ankers plays Larry Talbot’s love interest in The Wolf Man (1941) and Elsa Frankenstein in The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942). For more of Robert Paige, try Blonde Ice (1948), Abbott and Costello Go to Mars (1953), or Bye Bye Birdie (1963).

Monday, August 19, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: HOUSE OF DRACULA (1945)

Released in 1945, House of Dracula is one of the many monster movie sequels that Universal churned out in an effort to keep audiences coming back for more of their favorite fiends, and, like Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), or the later Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), this picture takes a “more is more” approach to its monsters. This particular mad monster party has some intriguing components, but it squanders its potential with a disastrous third act that doesn’t so much end as simply stop. Up until that frustrating finale, the picture has its appeal, especially in the performance of John Carradine as a thin, hypnotic Count and the creative twists applied to the mad doctor and hunchback staples.

Onslow Stevens stands at the center of the action as the good Doctor Edelmann, who is approached first by Dracula (John Carradine) and then by Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr.) for cures to their unique conditions. Dracula, as it turns out, really only wants to get close to Edelmann’s attractive nurse, Miliza (Martha O’Driscoll), and Edelmann pays a terrible price for trying to cure the vampire, even as his efforts to help Larry seem more hopeful. Edelmann also discovers the Frankenstein’s creature (Glenn Strange) in the caves beneath his castle, but his hunchbacked assistant, Nina (Jane Adams), repeatedly warns him against resurrecting the monster.

As the ostensible protagonist of the story, Onslow Stevens makes a good showing, especially during his Jekyll and Hyde moments later in the picture. Stevens is not particularly well-known today, but he worked a long and prolific career in film and television, and in Edelmann he has a role that allows him to play with many classic horror types at once. Edelmann is both Van Helsing and Victor Frankenstein as well as Jekyll and Hyde, a good man who resists evil until he is tragically overcome by it. His approach to the monstrous makes House of Dracula as much science fiction as horror; Edelmann treats vampirism as a blood condition and uses transfusions to combat it, although his treatment of lycanthropy proves far more successful, in part because Dracula doesn’t really to be cured, while Larry is ready commit suicide if he can't find a way to escape his werewolf curse.

The monsters, as usual, have the most fun here, with John Carradine leading the charge as an effective incarnation of the famous Count. Carradine has the mesmerizing eyes needed for this role, and the screen makes the most of them with several close-up shots. He doesn’t bother with a fake foreign accent, but his deep voice carries notes of aristocratic culture and seductive menace nonetheless. Dracula’s inevitable death scene begins the series of bad endings that plague the second half, but the Count still manages to make his influence felt beyond the grave. Lon Chaney, Jr. is back in familiar territory with his Larry Talbot role, which he wears as comfortably as a favorite suit, and we get some fun transformation sequences with lots of hair and teeth. Glenn Strange, however, has very little to do as the creature, whose few scenes are sometimes borrowed from earlier films with other actors in the makeup. As the love interest of both vampire and werewolf, Martha O’Driscoll is pretty but a bit flat, especially in her trance scenes with Dracula, and Jane Adam’s hunchbacked Nina proves a far more interesting female character. The abrupt ending that literally brings down the house on these characters is especially unfair to Nina, who ought to have a much better final moment than the throwaway treatment she receives.

Be sure to notice Lionel Atwill in one of his last screen roles as the police inspector. Erle C. Kenton, who directed House of Dracula, also headed up the terrific Island of Lost Souls (1932) as well as The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and House of Frankenstein (1944). For more early but memorable performances by John Carradine, see Stagecoach (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and Blood and Sand (1941); the actor appeared in more than 300 films and television programs, including many cult horror classics as well as serious Oscar contenders. Lon Chaney, Jr. made his first appearance as Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man (1941), but he went on to play the character many times, and he also starred in other monster roles in Son of Dracula (1943) and The Mummy's Curse (1944).

Onslow Stevens stands at the center of the action as the good Doctor Edelmann, who is approached first by Dracula (John Carradine) and then by Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr.) for cures to their unique conditions. Dracula, as it turns out, really only wants to get close to Edelmann’s attractive nurse, Miliza (Martha O’Driscoll), and Edelmann pays a terrible price for trying to cure the vampire, even as his efforts to help Larry seem more hopeful. Edelmann also discovers the Frankenstein’s creature (Glenn Strange) in the caves beneath his castle, but his hunchbacked assistant, Nina (Jane Adams), repeatedly warns him against resurrecting the monster.

As the ostensible protagonist of the story, Onslow Stevens makes a good showing, especially during his Jekyll and Hyde moments later in the picture. Stevens is not particularly well-known today, but he worked a long and prolific career in film and television, and in Edelmann he has a role that allows him to play with many classic horror types at once. Edelmann is both Van Helsing and Victor Frankenstein as well as Jekyll and Hyde, a good man who resists evil until he is tragically overcome by it. His approach to the monstrous makes House of Dracula as much science fiction as horror; Edelmann treats vampirism as a blood condition and uses transfusions to combat it, although his treatment of lycanthropy proves far more successful, in part because Dracula doesn’t really to be cured, while Larry is ready commit suicide if he can't find a way to escape his werewolf curse.

The monsters, as usual, have the most fun here, with John Carradine leading the charge as an effective incarnation of the famous Count. Carradine has the mesmerizing eyes needed for this role, and the screen makes the most of them with several close-up shots. He doesn’t bother with a fake foreign accent, but his deep voice carries notes of aristocratic culture and seductive menace nonetheless. Dracula’s inevitable death scene begins the series of bad endings that plague the second half, but the Count still manages to make his influence felt beyond the grave. Lon Chaney, Jr. is back in familiar territory with his Larry Talbot role, which he wears as comfortably as a favorite suit, and we get some fun transformation sequences with lots of hair and teeth. Glenn Strange, however, has very little to do as the creature, whose few scenes are sometimes borrowed from earlier films with other actors in the makeup. As the love interest of both vampire and werewolf, Martha O’Driscoll is pretty but a bit flat, especially in her trance scenes with Dracula, and Jane Adam’s hunchbacked Nina proves a far more interesting female character. The abrupt ending that literally brings down the house on these characters is especially unfair to Nina, who ought to have a much better final moment than the throwaway treatment she receives.

Be sure to notice Lionel Atwill in one of his last screen roles as the police inspector. Erle C. Kenton, who directed House of Dracula, also headed up the terrific Island of Lost Souls (1932) as well as The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and House of Frankenstein (1944). For more early but memorable performances by John Carradine, see Stagecoach (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and Blood and Sand (1941); the actor appeared in more than 300 films and television programs, including many cult horror classics as well as serious Oscar contenders. Lon Chaney, Jr. made his first appearance as Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man (1941), but he went on to play the character many times, and he also starred in other monster roles in Son of Dracula (1943) and The Mummy's Curse (1944).

Friday, August 16, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: LADY BE GOOD (1941)

Ann Sothern stars as songwriter Dixie Donegan, whose musical success with partner Eddie Crane (Robert Young) creates problems in their romantic relationship. The two divorce, although Dixie still loves Eddie and continues to work with him on hit songs, including the chart topper, “Lady Be Good.” Dixie’s pal, Marilyn (Eleanor Powell), schemes to get Dixie and Eddie back together by making Eddie jealous of suave singer Buddy (John Carroll), but her plans backfire in a series of comical misunderstandings and confrontations.

The story of Lady Be Good might throw a few more curveballs than are strictly necessary toward the end, but the contrast between Dixie and Eddie’s working and romantic relationships is interesting for its progressive approach. There’s no question of either partner giving up a career; these two need each other professionally as well as personally, but Dixie worries that success is ruining Eddie by making him care too much about social status. He also takes Dixie for granted, which she rightly sees as a serious problem. Eddie’s inability to manage a household is a joke typical of the film’s era, but Dixie becomes furious when he calls her over to the apartment not to apologize for his behavior but to get her to hire new help and straighten up the place. Resolution is only possible when Eddie doesn’t think of Dixie as his wife, as the last lines of the film make clear.

The other cast members contribute mostly to the comical or musical elements of the picture, sometimes both at once. Lionel Barrymore makes a sympathetic judge for both of Dixie’s divorce hearings, and Red Skelton is affably funny as one of the couple’s friends. As Skelton’s invariably hungry girlfriend, Lull, Virginia O’Brien has few lines and only one real song, but she makes the most of what she gets, and her musical performances are always a hoot. The Berry Brothers get more opportunities to strut their stuff, including a segment of the big “Fascinating Rhythm” production number; they do some amazing physical feats and will appeal to fans of the similar - but not identical - Nicholas Brothers. Eleanor Powell gets the best of both worlds as Dixie’s loyal pal and a featured performer for the musical scenes. Her duet with the dog, Buttons, is absolutely adorable, and her finale number in “Fascinating Rhythm” showcases her ability to hold the screen as a solo dancer. Powell is no floating accessory to a male dancer’s show; she taps with all the exuberant energy of Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire, and if you haven’t seen her before then this picture offers an excellent introduction to her signature style.

Look for brief appearances by Phil Silvers and Dan Dailey, and stop to appreciate Tom Conway’s marvelous voice in his scenes as Dixie’s lawyer. Lady Be Good won the Oscar for Best Original Song for “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” although the catchier Gershwin title number will linger in the viewer’s ears long after the movie ends. For more of Ann Sothern, see A Letter to Three Wives (1949) and the many Maisie films; Sothern earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her final screen performance in The Whales of August (1987). Robert Young also stars in Stowaway (1936), The Canterville Ghost (1944), and The Enchanted Cottage (1945). You’ll find Eleanor Powell in Broadway Melody of 1936 (1935), Born to Dance (1936), and Honolulu (1939). Red Skelton, Ann Sothern, Virginia O’Brien, and the Berry Brothers all reunite with director McLeod for Panama Hattie (1942), while Skelton, Powell, and O’Brien reteam for Ship Ahoy (1942).

Lady Be Good is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Summer Under the Stars: Bette Davis in DANGEROUS (1935)

This post is part of the Summer Under the Stars blogathon hosted by Sittin' on a Backyard Fence and ScribeHard on Film. Visit their blogs for links to all of the Bette Davis posts in conjunction with TCM's day honoring the star on August 14, 2013.

This post is part of the Summer Under the Stars blogathon hosted by Sittin' on a Backyard Fence and ScribeHard on Film. Visit their blogs for links to all of the Bette Davis posts in conjunction with TCM's day honoring the star on August 14, 2013. Bette Davis won her first Best Actress Oscar for Dangerous (1935), a romantic melodrama directed by Alfred E. Green and costarring Franchot Tone. As the title suggests, Davis plays a female who proves fatal to the men who are drawn to her flame, but the story is melodrama than noir because Davis’ anti-heroine knows that she’s bad news and agonizes over what to do about it. With its top-notch Davis performance and excellent darker role for Franchot Tone, Dangerous is a must-see picture for the leading lady’s fans, even if it isn’t as well-known today as most of her other Oscar-nominated films.

Davis plays alcoholic, has-been actress Joyce Heath, whose brilliant stage career collapsed when she became feared as a jinx on her plays. Her lovers have been unluckier still, as architect Don Bellows (Franchot Tone) discovers for himself when he takes Joyce in and promptly falls under her spell. Don breaks his engagement to socially prominent sweetheart Gail (Margaret Lindsay) and puts all of his money into financing a comeback for Joyce, but a terrible secret makes Joyce falter when Don presses her to marry him.

In Joyce Heath, Davis has an early version of the kind of character who would become her signature role, a wounded, emotional woman desperate for love and happiness but far too likely to lash out at those who only want to help her. Early on, Joyce has some of the low-rent, streetworn look of Mildred, the destructive character who had earned Davis her first Best Actress nomination in Of Human Bondage (1934). The drunk scenes are particularly reminiscent of the earlier role, but Joyce’s capacity for redemption prefigures great Davis characters like Julie Marsden in Jezebel (1938) and Fanny Skeffington in Mr. Skeffington (1944). Joyce is, like most of the really memorable Davis heroines, ready to go to extremes, especially in her willingness to take hints from Ethan Frome on how to solve romantic quandaries, but we sympathize with her because she is so unhappy and so ultimately determined to atone for her sins.

Davis has an adept costar in Franchot Tone as the latest lover to suffer for her bad luck. Tone played a lot of playboys and lovers in comedies during the 1930s, with memorable appearances in Bombshell (1933), Dancing Lady (1933), and The Girl from Missouri (1934), but here he gets to transform his happy golden boy into a miserable wreck. His cheerful face becomes gaunt and shadowy, his jaw hard, and his shoulders slumped as he gets deeper and deeper into a dangerous entanglement with Joyce, which eats away at his soul and drives him from the arms of his faithful girl. To her credit, Joyce tries to send Don away multiple times, honestly telling him that she will only bring him heartbreak and ruin, even as she yearns for him herself. Margaret Lindsay makes a plucky good girl foil to Davis’ Joyce, and Alison Skipworth does well in the role of Don’s middle-aged housekeeper. The weak link in the dramatic chain is John Eldredge as Gordon; he has a critical role to play late in the film, and it comes off badly, though to say too much about it is to spoil the plot for first-time viewers.

For more of Bette Davis’ early career, try Three on a Match (1932), The Petrified Forest (1936), and Marked Woman (1937). She continued to work for the rest of her life, making her final screen appearances in The Whales of August (1987) and Wicked Stepmother (1989) before her death in 1989. Franchot Tone stars in Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), Five Graves to Cairo (1943), and Advise and Consent (1962), and Margaret Lindsay also plays opposite Davis in Jezebel. For more from director Alfred E. Green, try Smart Money (1931), Baby Face (1933), and The Jolson Story (1946).

Full reviews to other Bette Davis films airing on August 14 can be found here:

THE PETRIFIED FOREST (1936)

JEZEBEL (1938)

THE LETTER (1940)

NOW, VOYAGER (1942)

DARK VICTORY (1939)

Monday, August 12, 2013

TCM Summer Under the Stars: Growing Up with Mickey Rooney

This post is part of the TCM Summer Under the Stars Blogathon hosted by Sittin' on a Backyard Fence and ScribeHard on Film. Visit their blogs to links for all of the blogathon posts!

Turner Classic Movies celebrates Mickey Rooney on August 13, 2013, with a full day of films starring the perpetually energetic but rather unlikely leading man. Even if it's a cliche, Mickey Rooney can really only be described as a living legend. Born in 1920, the 93 year old actor has more than 300 film and television appearances to his credit and is still working, with six roles in 2011 and 2012 combined. In a career that has spanned 87 years (so far), Rooney has been the classic Hollywood face that generations of viewers have grown up with and literally known all their lives.

Think about it. If every star born in 1920 were still alive and working today, you'd be seeing Yul Brynner, Gene Tierney, Walter Matthau, Ricardo Montalban, DeForest Kelley, Shelley Winters, Toshiro Mifune, Jack Webb, Denver Pyle, Virginia Mayo, Jack Elam, and Montgomery Clift turning up in the movies of the last two years. Maureen O'Hara, also born in 1920, has stuck around with Rooney, but she made her last TV movie appearance in 2000, more than a decade ago. Whatever you might think of Rooney's personal life (and it has been a doozy), you have to admire the willpower and determination of a man who entered the world that long ago and has been making his mark on it ever since.

The first audiences to grow up with Rooney saw him as a child himself in the Mickey McGuire shorts of the 1920s, which is where the young Joe Yule, Jr. picked up his new first name. In the 1930s, viewers knew him as the teen protagonist of the Andy Hardy films and other boys' stories, including Boys Town (1938), which is one of the films in the TCM lineup. You can also see Rooney in the Andy Hardy role in Family Affair (1936), and you can catch some of his other youthful performances in the early hours of the day on Tuesday. The TCM schedule includes two of the "kids putting on a show" pictures that Rooney made with Judy Garland: Strike Up the Band (1940) and Girl Crazy (1943).

Many of the later films on the TCM roster show Rooney's more adult, dramatic side, with performances inQuicksand (1950), The Strip (1951), and Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962). Youngsters who grew up in the 1970s, however, won't know Rooney from Pulp (1972) but will remember him in TV specials like The Year without a Santa Claus (1974) and Disney movies like Pete's Dragon (1977). The first movie that I really remember noticing Mickey Rooney in is The Black Stallion (1979), which I saw in the theater as a little girl and found utterly enthralling. I didn't know then that Rooney's role as a trainer was a tribute to his performances in Thoroughbreds Don't Cry (1937) and especially National Velvet (1944).

Even kids who are still growing up in 2013 have seen Rooney. He had a memorable role in Night at the Museum (2006) and a cameo in The Muppets (2011). That makes Rooney a great choice for some family viewing time on Tuesday. If your youngsters haven't gone back to school yet, try A Family Affair, Boys Town, Strike Up the Band, and Girl Crazy as some quality together time. If you miss them on TCM, you can find them on DVD and on streaming in various places. Watch with the kids and ask them if they recognize that funny guy and his distinctive voice. Maybe he sounds like Tod in The Fox and the Hound (1981)? Does he sound a lot like Sparky in Lady and the Tramp II: Scamp's Adventure (2001)? Maybe they remember that mean little old man who gave Ben Stiller a hard time in Night at the Museum. Then amaze the whippersnappers with the story of a little boy who grew up and grew old in front of the whole world, who made more than 300 movies and is still making millions of people laugh and cry today, thanks to the special, magical power of film.

For more about Mickey Rooney, see this post: "Putting on a Show: Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland," from the recent Dynamic Duos blogathon hosted by Classic Movie Hub.

Turner Classic Movies celebrates Mickey Rooney on August 13, 2013, with a full day of films starring the perpetually energetic but rather unlikely leading man. Even if it's a cliche, Mickey Rooney can really only be described as a living legend. Born in 1920, the 93 year old actor has more than 300 film and television appearances to his credit and is still working, with six roles in 2011 and 2012 combined. In a career that has spanned 87 years (so far), Rooney has been the classic Hollywood face that generations of viewers have grown up with and literally known all their lives.

Think about it. If every star born in 1920 were still alive and working today, you'd be seeing Yul Brynner, Gene Tierney, Walter Matthau, Ricardo Montalban, DeForest Kelley, Shelley Winters, Toshiro Mifune, Jack Webb, Denver Pyle, Virginia Mayo, Jack Elam, and Montgomery Clift turning up in the movies of the last two years. Maureen O'Hara, also born in 1920, has stuck around with Rooney, but she made her last TV movie appearance in 2000, more than a decade ago. Whatever you might think of Rooney's personal life (and it has been a doozy), you have to admire the willpower and determination of a man who entered the world that long ago and has been making his mark on it ever since.

The first audiences to grow up with Rooney saw him as a child himself in the Mickey McGuire shorts of the 1920s, which is where the young Joe Yule, Jr. picked up his new first name. In the 1930s, viewers knew him as the teen protagonist of the Andy Hardy films and other boys' stories, including Boys Town (1938), which is one of the films in the TCM lineup. You can also see Rooney in the Andy Hardy role in Family Affair (1936), and you can catch some of his other youthful performances in the early hours of the day on Tuesday. The TCM schedule includes two of the "kids putting on a show" pictures that Rooney made with Judy Garland: Strike Up the Band (1940) and Girl Crazy (1943).

Many of the later films on the TCM roster show Rooney's more adult, dramatic side, with performances inQuicksand (1950), The Strip (1951), and Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962). Youngsters who grew up in the 1970s, however, won't know Rooney from Pulp (1972) but will remember him in TV specials like The Year without a Santa Claus (1974) and Disney movies like Pete's Dragon (1977). The first movie that I really remember noticing Mickey Rooney in is The Black Stallion (1979), which I saw in the theater as a little girl and found utterly enthralling. I didn't know then that Rooney's role as a trainer was a tribute to his performances in Thoroughbreds Don't Cry (1937) and especially National Velvet (1944).

Even kids who are still growing up in 2013 have seen Rooney. He had a memorable role in Night at the Museum (2006) and a cameo in The Muppets (2011). That makes Rooney a great choice for some family viewing time on Tuesday. If your youngsters haven't gone back to school yet, try A Family Affair, Boys Town, Strike Up the Band, and Girl Crazy as some quality together time. If you miss them on TCM, you can find them on DVD and on streaming in various places. Watch with the kids and ask them if they recognize that funny guy and his distinctive voice. Maybe he sounds like Tod in The Fox and the Hound (1981)? Does he sound a lot like Sparky in Lady and the Tramp II: Scamp's Adventure (2001)? Maybe they remember that mean little old man who gave Ben Stiller a hard time in Night at the Museum. Then amaze the whippersnappers with the story of a little boy who grew up and grew old in front of the whole world, who made more than 300 movies and is still making millions of people laugh and cry today, thanks to the special, magical power of film.

For more about Mickey Rooney, see this post: "Putting on a Show: Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland," from the recent Dynamic Duos blogathon hosted by Classic Movie Hub.

Classic Films in Focus: SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS (1957)

Arriving late in the era of classic noir, director Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957) dispenses with any pretense at cool and dives right into the murkiest end of the cesspool, with Tony Curtis’ pretty boy face a thin veneer for unrelenting ugliness. This is the darkest, dirtiest sort of tale, a sordid story of ambition, jealousy, and betrayal. Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster play characters so utterly despicable that they’re painful to watch, even if their performances are brilliantly conceived and crackling with smart talk.

Curtis plays press agent Sidney Falco, who wants success badly enough to play lackey to powerful Broadway columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster). Hunsecker pushes Sidney to break up a romance between the columnist’s kid sister (Susan Harrison) and a jazz musician (Martin Milner), but even Sidney balks at the depths to which Hunsecker wants him to go. When smears in the papers don’t do the trick, Hunsecker arranges for Sidney to frame the lover for drug possession and then set him up for a beating from crooked cops.

The love story between the two young people is the least interesting thing going on in the picture, until the kid sister finally gets desperate enough to play a few of her brother’s tricks. The relationship that really grabs our attention is the sick entanglement of Hunsecker and Falco, two men on different rungs of the ladder but both of them as morally bankrupt as rotten souls could possibly be. Falco is perfectly willing to pimp himself to Hunsecker for the scraps the columnist will toss him, and he’s equally ready to pimp his girlfriend for the same cause. Hunsecker is such a control freak that he can’t stand for his sister to have her own life; he’s willing to destroy a good man just for having the temerity to court her. These two specimens of human depravity are tied to each other as much by hate as by need; Sidney sits smiling a sycophantic grin while Hunsecker holds court and cuts him down, taking every verbal blow without flinching, but underneath we get the sense that he’s keeping score. None of this can end well.

Our story revolves around vicious columnists whose livelihood depends on their poisonous tongues, and the dialogue offers plenty of barbed bons mots. One of the most famous bits, “I’d hate to take a bite out of you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic,” serves as an apt example of the whole. If you like the dirty kicks of crooked conversation, then this is the picture for you, with Curtis and Lancaster both delivering some of the most venomous double-edged lines ever conceived in classic film. It’s wickedly smart stuff, though it leaves a bad taste in the mouth and the mind. Only a rat could get away with saying such awful things, but only rats could behave as badly as Sidney and J.J. do. We long to see both of them poisoned with their own bait and thrown out with the rest of the trash.

Sweet Smell of Success did not do well when it first appeared, but today it’s considered an important accomplishment, despite its flaws. Alexander Mackendrick only directed a dozen films, but his other work includes Ealing comedies like The Man in the White Suit (1951) and The Ladykillers (1954). For more of Burt Lancaster’s films from this era, try Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), Run Silent Run Deep (1958), and Elmer Gantry (1960). Tony Curtis is best remembered for more likable characters in films like Some Like It Hot (1959), Operation Petticoat (1959), and The Great Race (1965). For more late noir, see The Killing (1956), Nightfall (1957), and Touch of Evil (1958).

Curtis plays press agent Sidney Falco, who wants success badly enough to play lackey to powerful Broadway columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster). Hunsecker pushes Sidney to break up a romance between the columnist’s kid sister (Susan Harrison) and a jazz musician (Martin Milner), but even Sidney balks at the depths to which Hunsecker wants him to go. When smears in the papers don’t do the trick, Hunsecker arranges for Sidney to frame the lover for drug possession and then set him up for a beating from crooked cops.

The love story between the two young people is the least interesting thing going on in the picture, until the kid sister finally gets desperate enough to play a few of her brother’s tricks. The relationship that really grabs our attention is the sick entanglement of Hunsecker and Falco, two men on different rungs of the ladder but both of them as morally bankrupt as rotten souls could possibly be. Falco is perfectly willing to pimp himself to Hunsecker for the scraps the columnist will toss him, and he’s equally ready to pimp his girlfriend for the same cause. Hunsecker is such a control freak that he can’t stand for his sister to have her own life; he’s willing to destroy a good man just for having the temerity to court her. These two specimens of human depravity are tied to each other as much by hate as by need; Sidney sits smiling a sycophantic grin while Hunsecker holds court and cuts him down, taking every verbal blow without flinching, but underneath we get the sense that he’s keeping score. None of this can end well.

Our story revolves around vicious columnists whose livelihood depends on their poisonous tongues, and the dialogue offers plenty of barbed bons mots. One of the most famous bits, “I’d hate to take a bite out of you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic,” serves as an apt example of the whole. If you like the dirty kicks of crooked conversation, then this is the picture for you, with Curtis and Lancaster both delivering some of the most venomous double-edged lines ever conceived in classic film. It’s wickedly smart stuff, though it leaves a bad taste in the mouth and the mind. Only a rat could get away with saying such awful things, but only rats could behave as badly as Sidney and J.J. do. We long to see both of them poisoned with their own bait and thrown out with the rest of the trash.