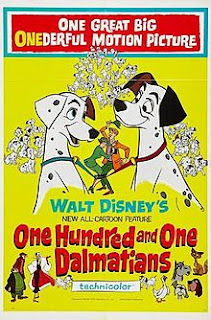

Fidelity to the 1961 animated classic is already an odd demand, not only because live action versions of that story were already made in the late 90s but because the original Disney movie is itself unfaithful to its source material in several significant ways. Dodie Smith's beloved 1956 children's novel features many characters and scenes that aren't in the Disney film. A third adult Dalmatian (the one actually named Perdita) is removed completely, with a dog originally named Missus assuming her name and erasing her from the story. The novel's Roger is wealthy because he is a "financial wizard" and not a struggling musician, so the family can afford all of their Dalmatians even when they end up with 101 of them (note that the 101st Dalmatian of the novel also isn't in the movie because he's the liver spotted love interest of the original Perdita). The Cruella of the book is more explicitly demonic and even more vicious than the movie version; she is also married to a submissive furrier who enables her obsession with fur coats. The changes don't make the Disney adaptation a bad movie, but they do make it a significantly different story from the novel. The live action versions get farther afield still, making Roger an American video game creator, Anita a fashion designer, and Cruella a fashion house owner and Anita's employer. In fact, the versions are so different (and set in different eras to boot) that the 2021 movie cannot possibly function as a true prequel to any of them.

|

| Tallulah! |

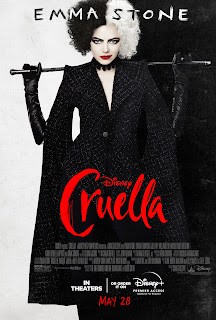

Instead, Cruella is its own story, a reinvention of the character that combines her most iconic traits with bits and pieces of the previous versions in order to make her a dynamic protagonist rather than a static villain. The movie does not attempt to make us like or forgive the other Cruellas; we like this new Cruella partly because she isn't them. Our glimpse of her childhood recalls the schoolgirl connection with Anita from the novel, her mannerisms are taken from the 1961 Disney film, and her fashion career is borrowed from the 1996 movie, but she is not simply a younger version of any of these characters. Disney opts to do something different by mining the tradition of the anti-heroine as filtered through one of the most important inspirations for the 1961 Cruella, the legendary actress and all around hellraiser Tallulah Bankhead. The film even signals the affiliation with a clip of Tallulah demonstrating her distinctive, throaty laugh in Alfred Hitchcock's 1944 thriller, Lifeboat. We see it play on a television set in a room with Estella/Cruella early in the story. Bankhead, known for her genius, self-destructive behavior, terrible driving, and theatrical personality, was definitely no saint, but this new version of Cruella has her charisma and charm as well as her less likeable qualities. It's refreshing to see a complicated, difficult, too-much female character be the heroine of her own life without having to be either a traditionally good person or a completely amoral anti-heroine of the Becky Sharp variety.

Because this Cruella is not the same as the previous versions, she can make different choices and develop different values. She loves fashion but isn't specifically obsessed with fur. She has a found family that she mistreats at times but ultimately loves, which includes several dogs. She is even the person who gives Pongo and Perdita to Roger and Anita, which she certainly wouldn't do if she wanted to make Dalmatian fur coats. Near the end of the movie, Cruella says about the Baroness: "The good thing about evil people is that you can always trust them to do something, well, evil." Cruella, despite her name, is not that kind of person, because her Estella side makes her capable of doing good. Currently, a sequel to the movie is in the works, and most fans and critics seem to expect it to launch us into the more familiar dog-napping, coat-making territory of the original story, but I really hope it doesn't go in that direction, because this Cruella deserves better. It's certainly possible that she might become a newer version of the Baroness, the murderous mother whom she deposes in the film, and therefore ruthless enough to become a full-blown villain, but it would be much more satisfying to see her continue to make bold new choices for herself, to continue to be the future she embodies in Cruella and not the past that she sees as the Baroness. To rope this Cruella back into the framework of the original story would be a grave disservice to her and to viewers who fell for her eccentric, outlandish personality.

I've watched Cruella a couple of times now, and while I have concerns about Disney's persistent efforts to strip mine its own properties, I think this movie is one of the best live action treatments of a classic Disney story and far more interesting and fun than the previous attempts to cash in on the Dalmatians' popularity, largely because it isn't about the dogs. It's fun, it's visually engaging, it features terrific performances from Stone and Emma Thompson, and it offers us a Disney "heroine" who is very different from the usual crowd of princesses and whose transgressive modernity is part of her appeal. I don't care that it isn't actually a prequel to 101 Dalmatians; that's why it works. This Cruella might well be brilliant and bad and a little bit mad, but she's more 70s counterculture rock goddess than maniacal puppy murderer, and I'd like to see any additional films about her continue to give her the freedom to be her own version of herself.