WARNING! This post contains major spoilers for THE DAMNED DON'T CRY and other classic noir films. Proceed at your own risk.

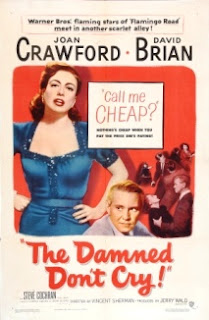

When I showed The Damned Don't Cry (1950) to my lifetime learners as the final film of our Joan Crawford series, they were especially struck by the open ending of the story, which leaves us wondering about the ultimate fate of protagonist Ethel Whitehead, aka Mrs. Lorna Hansen Forbes. Director Vincent Sherman and leading lady Crawford carry us through a dark journey over the course of the picture, which is equal parts melodrama and film noir as it shows us Ethel's seduction by avarice and ambition. My lifetime learners fully expected Ethel to die or at least go to prison in the movie's final scenes, but neither happens. Why doesn't Ethel pay a heavier price for her actions, and why are we surprised that she doesn't? Those questions deserve some consideration, especially since both melodrama and noir are known for killing off their most deeply flawed protagonists. Ethel Whitehead is, indeed, deeply flawed, but the film consistently displays a degree of sympathy for her that resists reading her as a villain or reaching a harsher conclusion as poetic justice for her crimes.

The picture opens with murder and scandal as the wealthy Mrs. Lorna Hansen Forbes is revealed as a fraud, but we are soon provided with her backstory. Ethel Whitehead is a poor woman from a working class family, scraping to get by and unable to afford any of the things her beloved young son desires. When the son tragically dies, Ethel feels that she has nothing to lose by leaving her old life behind. She heads to New York City and gets a job as a dress model, which she uses as a springboard to better - but increasingly criminal - prospects. Along the way she entangles Martin Blackford (Kent Smith), an accountant who accepts lucrative jobs with mobsters to win her love, but she abandons Martin in favor of the boss himself, the ruthless but refined George Castleman (David Brian). George remakes Ethel into socialite oil heiress Lorna, but his favors come at a price, and Ethel eventually finds herself dispatched to California on a dangerous mission to uncover the treachery of mob underling Nick Prenta (Steve Cochran).Given that Ethel abandons her husband and parents, ruins Martin's life, misrepresents her identity and social standing, and knowingly gets involved with gangsters, we might imagine death or prison to be more than justified, and perhaps even obligatory given the Hays Code demand that crime always be punished. She also demonstrates dissatisfaction with married poverty and a desire to have money and nice possessions, and that kind of rebellion against conservative, patriarchal values usually doesn't end well for female characters, especially after the enforcement of Hays in 1934, which brought an end to heroines who cheerfully hustle their way to the top. Ethel wants more, and wanting more is very dangerous to a woman's life expectancy in Hays era films. Crawford's heroine in Humoresque (1946) drowns herself as penance for her sins, while her rival Bette Davis pays the ultimate price in pictures like Of Human Bondage (1934), Jezebel (1938), The Letter (1940), and Another Man's Poison (1951). Although melodramas sometimes kill their heroines, noir's femme fatale types are especially likely to meet violent ends. Mary Astor's slippery Brigid faces hanging or hard time at the end of The Maltese Falcon (1941), while Barbara Stanwyck eats lead in both Double Indemnity (1944) and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946). If we hold Ethel fully responsible for Martin's corruption and Nick's murder, then we might conclude that she deserves the same fate as her "sisters under the mink," as Gloria Grahame says in The Big Heat (1953) (her character doesn't make it out alive, either).

Ethel, however, is never presented as a true femme fatale, and the film repeatedly balances her materialism with scenes that humanize her. We sympathize with her desire to get out of her miserable life in the oil fields and away from her brutish father and domineering husband. Her child's death breaks her resolve to endure that life any longer, and we can't blame her for running away from a hollow existence without the sole joy she found there. As a dress model, Ethel at first balks at the shady aspects of the job, but she grows accustomed to trading moral qualms for money by degrees. The rewards are concrete - a nicer place, better food, prettier clothes - while the costs are less tangible. Ethel doesn't intentionally corrupt Martin or plan to jilt him from the beginning; she really cares about him but can't stop herself from taking the opportunity that George represents. She holds no animosity toward George's pitiful wife and is, in fact, gentle with her in their one scene together. When George orders her to California, Ethel obeys because she thinks she loves him, but her sympathy for Nick and revulsion at the idea of murder prove stronger than her loyalty to George. Martin, who has clearly resented Ethel for his fall from grace, similarly reveals that his love for her trumps other concerns, and his forgiveness encourages our own.

By the end of the film, Nick and George are both dead, Martin has turned police informant, and Ethel has been shot by George after returning to her parents' spartan hovel. Her ruse as Lorna Hansen Forbes is definitely over, especially with the source of her illicit wealth now gone. The final scenes focus again on Ethel's humanity and the better aspects of her nature. We see her reunited with her parents and with Martin, whom she bravely tries to protect by going alone to face the vengeful George. After George shoots Ethel, the movie could easily have ended with her death, but instead we see that she survives to be comforted by her parents and questioned by both reporters and the police. Martin is notably absent at the conclusion, possibly in police custody and possibly on the lam; we get no hint about a reunion with Ethel. The clusters of policemen all around the house suggest that Ethel might also be looking at jail, but instead of speculating about her trial the departing reporters wonder if she'll make another attempt to escape the stark poverty of her home. "Wouldn't you?" asks one of the reporters, and the other nods his answer with certainty. We leave the story not knowing the fates of either Ethel or Martin, but we're encouraged by the last bit of dialogue to wonder what happens next.

While this open ending might well surprise viewers expecting a definite conclusion, it lets The Damned Don't Cry obey the letter of the Hays Code while still offering us hope for a flawed heroine whom the narrative encourages us to care about in spite of her flaws. Ethel has already suffered a great deal, although of course a narrow-minded moralist like Joseph Breen would be happy to see her die in the dirt or the execution chamber. Instead, we get an ending that lets the viewer imagine what happens next according to his or her own preferences. Personally, I like to imagine that Ethel and Martin get back together and disappear into new identities far away from the shadow of their shared past, maybe somewhere in Mexico. I don't blame Ethel for wanting out of her miserable, downtrodden life, but I hope that she can find a via media to real happiness somewhere between poverty and ruthless materialism. A less sympathetic viewer might assume that jail time, if nothing worse, awaits Ethel as punishment for her crimes, and the hovering police officers certainly make that option plausible. If we want more from the ending of The Damned Don't Cry, that in itself makes us more like Ethel than some viewers who judge her harshly might care to admit. How much is someone allowed to want? How much wanting is too much, and what should happen to someone who wants it? Like Ethel, we're left wanting more, but we'll have to make it up ourselves to get it.

If you're interested in reading more of my posts about Joan Crawford, check out the following:

Loved this first-rate post on one of my favorite noirs. Like you, I like to think that Ethel wound up with Marty-- I certainly don't think either of their 'crimes' warrant any kind of severe punishment. I think they've both deserved their moment out of the sun.

ReplyDelete