Whatever the outcome, there's something fascinating about the combination of Roger Corman and Francis Ford Coppola, the producer and director, respectively, of the low-budget shocker, Dementia 13 (1963). While the movie leaves a lot to be desired, thanks in part to disagreements between the two and tinkering by Corman, there's enough going on to make it watchable, and even mildly entertaining, for the brief seventy five minutes that it runs. This is absolutely a B movie of the drive-in variety, the kind of horror slasher that amorous teenagers of the era only half-watched in between their make out sessions, with periodic flashes of violence and gore to make the audience look up. Still, if you're interested in the influence of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960), Dementia 13 provides a good example of the way in which the earlier picture helped to establish the visual vocabulary of the slasher genre.

Luana Anders stars as Louise Haloran, a greedy bride who covers up her husband's death from a fatal heart attack in order to cash in on his part of his mother's will. Luana then goes to work on Lady Haloran (Eithne Dunne), who still grieves the drowning death of her youngest child, Kathleen. Louise promises Lady Haloran that Kathleen's spirit speaks to her and will soon show the obsessed mother a sign, but Louise finds out that she isn't the only person on the estate with sinister secrets. There's a killer on the loose, one who also has an obsession with the long dead Kathleen. Is it one of the brothers, Richard (William Campbell) and Billy (Bart Patton), or the unnerving Dr. Caleb (Patrick Magee) who wields the deadly ax?

Stylistically and thematically, Dementia 13 resembles the work of William Castle more than it does either Corman or Coppola; its original theatrical release even included a gimmicky introduction that supposedly justified the otherwise nonsensical title. It borrows liberally from Psycho but never achieves the narrative tension of the Hitchcock film, even though its black-and-white cinematography does occasionally provide some very effective images. The first murder makes particular use of Hitchcock's visual style, imitating the iconic shower scene in its editing, its characters, and its use of blood and water. Later, an onscreen decapitation delivers a gory shock but doesn't really advance the story, since the character being killed has nothing to do with the central plot. More indicative of things to come are the attack on Lady Haloran in Kathleen's abandoned playhouse and the gruesome reveal of a semi-nude corpse hanging in a shed; moments like these become more or less obligatory in the slasher films that follow.

The characters assembled for this fatal gathering lack really insightful development but do offer hints and suggestions of interesting psychological issues. Louise is very much an anti-heroine, heartless and manipulative, and Luana Anders plays her sly self-interest well. Billy suffers from nightmares and some kind of post-traumatic disorder, having witnessed his sister's death when he was just a child, while the taciturn Richard avoids any discussion of the family tragedy, even with his fiancee, Kane (Mary Mitchel). Both actors in the surviving brother roles do their best with the material at hand, although Peter Read, who plays John, has to make the most of his opening heart attack scene. A more talented actress might have made something really Gothic out of Lady Haloran, but Eithne Dunne at least looks the part; her scene in the playhouse is definitely her best moment in the picture. She and Patrick Magee are both actually Irish, although neither of them sound like it, and there's something very unsettling about Magee's performance as the doctor. Some of the bizarre behavior is simply misdirection, meant to keep the audience guessing about the killer's identity until the end of the movie, but even necking teenagers in the backseats of cars probably figured it out long before the final reveal.

Roger Corman's other films from 1963 include The Terror, The Raven, and The Haunted Palace, all of which he directed and produced. Francis Ford Coppola went on to fame and Oscar glory as the director of The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979), but he revisited horror with Dracula in 1992. Luana Anders, William Campbell, and Patrick Magee can all be found in Corman's The Young Racers (1963), on which Coppola also worked as the second unit director. You can see more of Anders in Corman's 1961 Poe film, The Pit and the Pendulum. William Campbell had the longest and most varied career of the movie's cast, but his most memorable role might be as the Klingon Koloth in the Star Trek episode, "The Trouble with Tribbles." At the time that they made Dementia 13, actors Bart Patton and Mary Mitchel were married in real life; they divorced in 1980.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Monday, October 26, 2015

Classic Films in Focus: AND THEN THERE WERE NONE (1945)

Eight guests and two house servants gather to spend the weekend on a remote island estate at the command of the secretive Mr. U.N. Owen, whom none of them seem to know. A recording soon informs them that their host is privy to their terrible secrets; each is accused of causing the death of another person and getting away with it. The guests are then rapidly dispatched, each in a way that corresponds to the nursery song, "Ten Little Indians," and every death is accompanied by the destruction of another Indian statue on the dining room table. Realizing that one of them must be the killer, the shrinking group of survivors tries to identity the murderer, but alliances within the group both help and hinder the process.

It's difficult to say very much about the mystery itself without giving away the ending, although most viewers who come to the movie will already know it from previous encounters with the frequently performed play. The conclusion does differ significantly from that of Christie's 1939 novel (the title also differs, and for good reason), although most of the characters carry over in somewhat altered forms. Christie's premise has been copied, parodied, and reworked countless times, but it's still a very good setup for a mystery, and the criminal conduct of most of the guests makes us fairly nonchalant about their deaths. The absence of a proper detective - Roland Young's dense Mr. Bloor definitely doesn't count - leaves the nervous survivors to figure things out for themselves, while the audience makes it own guesses as each new death removes another suspect from the list. No two deaths are exactly the same, although, this being Agatha Christie, there is a decided preference for poison overall, which helps to keep the women and older male characters in play as potential killers.

For movie buffs, the real pleasure of this particular production is the large and impressive cast, including Walter Huston as the alcoholic Dr. Armstrong and Barry Fitzgerald as Judge Quincannon. Both of those actors are celebrated for their strong character performances, and here they simply revel in their delightfully suspicious roles, especially when they join forces in the third act. Judith Anderson, best remembered as Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca (1940), plays the sanctimonious Miss Brent with heartless hauteur, while C. Aubrey Smith is rather tragic as the elderly general. Richard Haydn and Mischa Auer both play their characters for laughs, with Haydn as the long-suffering butler, Rogers, and Auer as the "professional house guest" prince. Sadly, Auer's character is the first to go, but he makes the most of his brief time on screen. Louis Hayward and June Duprez play the attractive young couple who fall for each other even as the murderer closes in, and they have fine chemistry together, especially when each suspects that the other might be the killer. Rounding out the crowd are Roland Young as the ineffectual Mr. Bloor and Queenie Leonard as the housekeeper, Mrs. Rogers, whose early death the other characters lament mainly because it deprives them of their cook.

If the black comedy of And Then There Were None appeals, follow up with Murder by Death (1976) or Clue (1985), both of which take their cues from Christie's plot. For more film adaptations of Agatha Christie, try Witness for the Prosecution (1957), Murder on the Orient Express (1974), and The Mirror Crack'd (1980). Rene Clair also directed The Ghost Goes West (1935), The Flame of New Orleans (1941), and I Married a Witch (1942). See Barry Fitzgerald in Going My Way (1944), where his performance earned nominations for both Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor (he won the latter). Walter Huston won an Oscar for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), but don't miss his wild performance in Kongo (1932). Look for both C. Aubrey Smith and June Duprez in The Four Feathers (1939), and catch Louis Hayward in The Man in the Iron Mask (1939). Oddly enough, both Richard Haydn and Queenie Leonard, who play a married couple in this film, provided voices for the 1951 Disney classic, Alice in Wonderland.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

CMBA Blogathon: THE HARVEY GIRLS (1946)

The theme for this year's CMBA Blogathon is "Planes, Trains, & Automobiles," which makes the 1946 musical, The Harvey Girls, an obvious choice. The movie won an Oscar for its train themed song, "On the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe," and it depicts, in a fictionalized and colorful way, the importance of the train in bringing women to the American West. Adapted from a novel by Samuel Hopkins Adams, The Harvey Girls stars Judy Garland, Cyd Charisse, and Virginia O'Brien as three young women who head West on the train to find new opportunities and romance. While it's not a perfect picture, this is a fun, lively musical that tells an often unknown story about women's part in settling the frontier, made even more entertaining by the presence of outstanding actors like Angela Lansbury, Marjorie Main, Ray Bolger, and John Hodiak.

The Harvey Girls were real people; these young women went West to staff the Harvey Houses that sprang up along the railroad lines in the late 19th century. Fred Harvey recruited young women with good backgrounds and civilized manners to work in his establishments, where train passengers found a short rest and a good meal during their stops. For women of that time, there were few respectable job opportunities out West, but the Harvey Houses provided good wages along with room and board. The crisp uniforms and cheerful manners of the Harvey Girls brought a wholesome, civilized femininity to rough country, and their presence helped to tame wild frontier towns. One notable Harvey House location was the Grand Canyon, where the Fred Harvey Company provided concessions and visitor services until 1968. Today, the El Tovar Hotel at the South Rim includes a display honoring the Harvey Girls and the 1946 film tribute to their legacy. Becoming a Harvey Girl changed the lives of many women who yearned for independence and adventure. Over 100,000 young women took the opportunity that the Harvey Houses offered, and you can learn more about their stories by watching the trailer for the 2013 documentary film, The Harvey Girls: Opportunity Bound.

In the movie, Judy Garland's character, Susan, doesn't set out to be a Harvey Girl at all. She responds to a call for a mail-order bride, but when she meets the intended groom (Chill Wills) she jumps at the chance to become a Harvey Girl like the other young women on her train. Marjorie Main plays a funny but effective chaperone and manager for the young ladies in her charge, while Cyd Charisse and Virginia O'Brien appear as two Harvey Girls who befriend Susan. The girls encounter a different type of Western womanhood in Angela Lansbury's saloon singer, Em, who doesn't appreciate the competition or the straitlaced morality of the new arrivals. Susan attracts the interest of the bar's owner, Ned Trent (John Hodiak), while Virginia O'Brien's character, Alma, engages in an awkward but entertaining romance with Chris (Ray Bolger). Sadly, O'Brien disappears from the movie in the third act, thanks to shooting delays that made her pregnancy impossible to hide, but she does get in a particularly funny performance with the song, "The Wild, Wild West."

If The Harvey Girls romanticizes the real experiences of the women who staffed the restaurants on the Santa Fe lines, it also depicts women as individuals who went West for many reasons, and not just as daughters, wives, or prostitutes. Women's Westerns have been few and far between in Hollywood history, but when they do come along they reveal fascinating hints at stories that have largely been left untold. As a musical comedy, The Harvey Girls is lighter and sweeter than Westward the Women (1951) or cattle queen dramas like The Furies (1950) and Johnny Guitar (1954), but it does a great job leaving the viewer wanting to know more about the real women who took that chance for a new life out West. Trains made Harvey Houses necessary, and Harvey Houses made a place for young women to earn a living and lead independent lives. That's a theme worth singing about!

You can find a full-length review of The Harvey Girls in my book, Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching, available on Kindle at Amazon.com. For more about The Harvey Girls, try the 1994 book by Lesley Poling-Kempes, The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West.

The Harvey Girls were real people; these young women went West to staff the Harvey Houses that sprang up along the railroad lines in the late 19th century. Fred Harvey recruited young women with good backgrounds and civilized manners to work in his establishments, where train passengers found a short rest and a good meal during their stops. For women of that time, there were few respectable job opportunities out West, but the Harvey Houses provided good wages along with room and board. The crisp uniforms and cheerful manners of the Harvey Girls brought a wholesome, civilized femininity to rough country, and their presence helped to tame wild frontier towns. One notable Harvey House location was the Grand Canyon, where the Fred Harvey Company provided concessions and visitor services until 1968. Today, the El Tovar Hotel at the South Rim includes a display honoring the Harvey Girls and the 1946 film tribute to their legacy. Becoming a Harvey Girl changed the lives of many women who yearned for independence and adventure. Over 100,000 young women took the opportunity that the Harvey Houses offered, and you can learn more about their stories by watching the trailer for the 2013 documentary film, The Harvey Girls: Opportunity Bound.

In the movie, Judy Garland's character, Susan, doesn't set out to be a Harvey Girl at all. She responds to a call for a mail-order bride, but when she meets the intended groom (Chill Wills) she jumps at the chance to become a Harvey Girl like the other young women on her train. Marjorie Main plays a funny but effective chaperone and manager for the young ladies in her charge, while Cyd Charisse and Virginia O'Brien appear as two Harvey Girls who befriend Susan. The girls encounter a different type of Western womanhood in Angela Lansbury's saloon singer, Em, who doesn't appreciate the competition or the straitlaced morality of the new arrivals. Susan attracts the interest of the bar's owner, Ned Trent (John Hodiak), while Virginia O'Brien's character, Alma, engages in an awkward but entertaining romance with Chris (Ray Bolger). Sadly, O'Brien disappears from the movie in the third act, thanks to shooting delays that made her pregnancy impossible to hide, but she does get in a particularly funny performance with the song, "The Wild, Wild West."

If The Harvey Girls romanticizes the real experiences of the women who staffed the restaurants on the Santa Fe lines, it also depicts women as individuals who went West for many reasons, and not just as daughters, wives, or prostitutes. Women's Westerns have been few and far between in Hollywood history, but when they do come along they reveal fascinating hints at stories that have largely been left untold. As a musical comedy, The Harvey Girls is lighter and sweeter than Westward the Women (1951) or cattle queen dramas like The Furies (1950) and Johnny Guitar (1954), but it does a great job leaving the viewer wanting to know more about the real women who took that chance for a new life out West. Trains made Harvey Houses necessary, and Harvey Houses made a place for young women to earn a living and lead independent lives. That's a theme worth singing about!

You can find a full-length review of The Harvey Girls in my book, Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching, available on Kindle at Amazon.com. For more about The Harvey Girls, try the 1994 book by Lesley Poling-Kempes, The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West.

Monday, October 19, 2015

Classic Films in Focus: CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF (1958)

Newman plays alcoholic football has-been Brick Pollitt, who returns to his family's plantation home with his wife, Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor), for the birthday of the ailing Pollitt patriarch, Big Daddy (Burl Ives). Brick breaks his leg in a drunken attempt to relive high school glories, but his real problems are the recent death of his best friend, Skipper, and his subsequent estrangement from his wife, whom he punishes for her role in Skipper's death by withholding sex. Brick's brother, Gooper (Jack Carson), and his aggressively fertile wife, Mae (Madeleine Sherwood), spend their time eavesdropping on Brick and Maggie and plotting ways to get a bigger piece of Big Daddy's considerable estate, while Big Momma (Judith Anderson) clings to the hope that Big Daddy's illness is not as serious as everyone else suspects.

Newman and Taylor set the screen on fire with their depiction of a fraught relationship on the very edge of annihilation; they are both impossibly sexy, prowling around in states of undress and simultaneously tempted to tear each other's clothes off or tear each other apart. The film makes a point of Brick's heterosexuality by having Newman secretly bury his face in Maggie's nightgown even as he rejects her from behind a closed bathroom door. He wants her badly but feels driven to hurt both her and himself because of his guilt over Skipper. Taylor's Maggie, the titular cat, never stops fighting to win Brick back, but she also has to contend with Goober and Mae and their brood of obnoxious children; her genuine sympathy for Big Daddy and Big Momma contrasts with her loathing for Goober's family, which can sometimes make her seem shrill. Brick proves the more dynamic of the pair, since he has to come to grips with his alcoholism, his marriage, and his relationship with his father during a condensed period of time. The symbolic shift occurs when he breaks his crutch while trying to flee the plantation in a pouring rain; his guilt, his booze, and his anger are all crutches that he'll have to give up if he wants to survive.

The supporting cast members have less attractive but equally complex roles to play. Burl Ives, best remembered today as the jovial voice of the Snowman in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), gets a chance to demonstrate his belligerent side with Big Daddy, a bad-tempered old tyrant who bullies and harasses his family but doesn't know how to love them. He and Judith Anderson both walk a very fine line in playing characters who are often difficult and even exasperating but ultimately have to be sympathetic. The film shows us the warts first and then asks us to understand these wounded, yearning older people; in one especially powerful scene, a heartbroken Big Momma holds Big Daddy's birthday cake and laments, "In all these years you never believed I loved you. And I did." Anderson invests her character with equal parts foolishness and anguished affection, and in lines like that her performance goes straight to the heart. Less likable are Jack Carson and Madeleine Sherwood as Gooper and Mae, both grasping and disingenuous schemers who treat reproduction like an arms race. Carson gets to redeem Gooper just a bit near the very end, but Sherwood's Mae is an unrepentant bitch, and her performance is gloriously vicious throughout, with Mae getting a lot of the movie's best lines. You'll itch to slap the insufferable "Sister Woman" cockeyed, especially after that crack about the "Punch Bowl," and her comeuppance is one of the finale's sweetest payoffs.

Richard Brooks, who directed Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, returned to Williams material and Paul Newman with Sweet Bird of Youth (1962); Brooks also directed Elmer Gantry (1960), The Professionals (1966), and In Cold Blood (1967). For more film adaptations of Tennessee Williams, try Baby Doll (1956), Suddenly, Last Summer (1959), and The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1961). Elizabeth Taylor's third husband, Michael Todd, died in a plane crash during the production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, making this film a particularly difficult effort for her; see her in happier times in Lassie Come Home (1943) or in later roles in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and The Taming of the Shrew (1967). Don't miss Paul Newman in The Hustler (1961), Cool Hand Luke (1967), and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). For the sake of contrast, see Judith Anderson's terrifying performance as Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca (1940) and Jack Carson's comedy shenanigans in Romance on the High Seas (1948) and Dangerous When Wet (1953).

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Memorial Post: Grendel (1995-2015)

We said goodbye to our 20 year old cat, Grendel Graymalkin Kagemusha Sparks, this morning. He had been with me since he was just a few weeks old; he was born to a feral cat who lived under my grandfather's potato shed, and during Hurricane Opal he was rescued from the storm by my parents, who fed him and his two siblings with an eyedropper until they could catch the mother cat. In his prime he was an 18 pounder and an avid catcher of insects. He had fixed opinions about laps, fresh water, and the best spot to take a nap. He was, in the words of Samuel Johnson, "a very fine cat indeed," and we are going to miss him.

I don't think I can bear to watch them this Halloween, but if you happen to watch The Black Cat (1934) or The Black Cat (1941), spare a moment to think of our dear old boy, whom we were lucky to call our own for so many years.

Rest in peace, fuzzy kitty boy.

I don't think I can bear to watch them this Halloween, but if you happen to watch The Black Cat (1934) or The Black Cat (1941), spare a moment to think of our dear old boy, whom we were lucky to call our own for so many years.

Rest in peace, fuzzy kitty boy.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

Classic Films in Focus: BLACK SABBATH (1963)

Mario Bava's 1963 Italian-French horror anthology, Black Sabbath, is both lurid and literary, much like Roger Corman's Poe films from the same era, but without the cheeky black humor that pervades the Corman canon. Even more so than in Corman's loosest adaptations, the literary pedigrees of Bava's three chilling tales are hopelessly muddled, but their questionable origins don't diminish their effectiveness. Each story in this trio has something different to offer: the first is a subversive thriller, the second a Gothic vampire tale, and the third a ghastly story of otherworldly revenge. On hand as host and star of the second segment is genre icon Boris Karloff, delightful even when dubbed and looking truly terrifying as the family patriarch in "The Wurdulak." While not, perhaps, as perfect an example of Bava's style as Black Sunday (1960), this anthology picture makes a solid introduction to the Italian auteur, and it usually finds a place on lists of Bava's most significant works.

The collection opens with "The Telephone," in which a beautiful young woman (Michele Mercier) fears the threats of a murderous caller and enlists the aid of her former lesbian lover (Lydia Alfonsi) to keep the attacker away. In the second story, "The Wurdulak," a young gentleman (Mark Damon) meets a family horrified by the possibility that their patriarch (Boris Karloff) has returned home as a vampire intent on killing those he most loved in life. The final story, "The Drop of Water," depicts a nurse (Jacqueline Pierreux) who steals a ring from a dead woman, only to face a ghost's relentless vengeance.

Of the three stories, "The Wurdulak" is the grandest and the most like Bava's most celebrated feature length tales. It's awash in Gothic atmosphere but driven by a nihilistic attitude that leaves no potential victim off limits. The story is adapted from a novella by Aleksey Tolstoy, a cousin to Leo, but still a successful writer in his own right. Karloff looks terrifying as Gorca, especially in the later scenes, and Susy Andersen is lovely as his daughter, Sdenka. The third segment, "The Drop of Water," will delight fans of a sinister face, since its chief attraction is the ghoulish countenance of the dead woman from whom the nurse takes a valuable ring. It's definitely the stuff of nightmares, and the darkly ironic ending provides a touch of grim humor, too. The least compelling story leads the set; "The Telephone" is more straightforward thriller material, with lesbian sexuality shaking up the usual misogyny of such tales but not really alleviating our sense of Rosy, the attractive victim, as an object of voyeurism and violent desire. Very little can be made of the film's writing credits for either "The Drop of Water" or "The Telephone," except that Bava clearly wants to invest his anthology with a classy literary sensibility.

The horror anthology picture is a peculiar but enduring subgenre, and Bava's entry makes a useful companion to Corman's Tales of Terror (1962) and Sidney Salkow's Twice-Told Tales (1963), both of which feature Vincent Price as their primary star. Bava limits his signature star's screen time to bookend sequences and the middle story, but Karloff provides the same kind of cachet to the proceedings, just as Peter Cushing does in From Beyond the Grave (1974). Later examples of the anthology include The House That Dripped Blood (1971), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), Creepshow (1982), and Cat's Eye (1985), which show the format's ongoing appeal as a way to give horror audiences a variety of shocks in a single theatrical experience. For Bava, the anthology approach allows for a more condensed exploration of themes he engaged over the course of his career; in addition to true horror pictures, he also made thrillers like The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) and Rabid Dogs (1974), so his inclusion of "The Telephone" in Black Sabbath makes sense, even if it seems very different from the other two segments.

Be sure to watch the original release version of Black Sabbath, known as I tre volti della paura in Italian; the English dubbed AIP version changes the order of the stories and makes drastic alterations to "The Telephone." For more of Mario Bava, see The Whip and the Body (1963), Kill, Baby, Kill (1966), and Baron Blood (1972). Boris Karloff's other films from 1963 include The Raven, The Terror, and The Comedy of Terrors, proving that the iconic star was still much in demand over forty years after his screen debut. You'll find Mark Damon in Corman's House of Usher (1960) and in later continental shockers like The Devil's Wedding Night (1973) and Hannah, Queen of the Vampires (1973). Michele Mercier is best remembered as the star of Angelique (1964) and its sequels, but she returns to the horror genre for Web of the Spider (1971).

The collection opens with "The Telephone," in which a beautiful young woman (Michele Mercier) fears the threats of a murderous caller and enlists the aid of her former lesbian lover (Lydia Alfonsi) to keep the attacker away. In the second story, "The Wurdulak," a young gentleman (Mark Damon) meets a family horrified by the possibility that their patriarch (Boris Karloff) has returned home as a vampire intent on killing those he most loved in life. The final story, "The Drop of Water," depicts a nurse (Jacqueline Pierreux) who steals a ring from a dead woman, only to face a ghost's relentless vengeance.

Of the three stories, "The Wurdulak" is the grandest and the most like Bava's most celebrated feature length tales. It's awash in Gothic atmosphere but driven by a nihilistic attitude that leaves no potential victim off limits. The story is adapted from a novella by Aleksey Tolstoy, a cousin to Leo, but still a successful writer in his own right. Karloff looks terrifying as Gorca, especially in the later scenes, and Susy Andersen is lovely as his daughter, Sdenka. The third segment, "The Drop of Water," will delight fans of a sinister face, since its chief attraction is the ghoulish countenance of the dead woman from whom the nurse takes a valuable ring. It's definitely the stuff of nightmares, and the darkly ironic ending provides a touch of grim humor, too. The least compelling story leads the set; "The Telephone" is more straightforward thriller material, with lesbian sexuality shaking up the usual misogyny of such tales but not really alleviating our sense of Rosy, the attractive victim, as an object of voyeurism and violent desire. Very little can be made of the film's writing credits for either "The Drop of Water" or "The Telephone," except that Bava clearly wants to invest his anthology with a classy literary sensibility.

The horror anthology picture is a peculiar but enduring subgenre, and Bava's entry makes a useful companion to Corman's Tales of Terror (1962) and Sidney Salkow's Twice-Told Tales (1963), both of which feature Vincent Price as their primary star. Bava limits his signature star's screen time to bookend sequences and the middle story, but Karloff provides the same kind of cachet to the proceedings, just as Peter Cushing does in From Beyond the Grave (1974). Later examples of the anthology include The House That Dripped Blood (1971), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), Creepshow (1982), and Cat's Eye (1985), which show the format's ongoing appeal as a way to give horror audiences a variety of shocks in a single theatrical experience. For Bava, the anthology approach allows for a more condensed exploration of themes he engaged over the course of his career; in addition to true horror pictures, he also made thrillers like The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) and Rabid Dogs (1974), so his inclusion of "The Telephone" in Black Sabbath makes sense, even if it seems very different from the other two segments.

Be sure to watch the original release version of Black Sabbath, known as I tre volti della paura in Italian; the English dubbed AIP version changes the order of the stories and makes drastic alterations to "The Telephone." For more of Mario Bava, see The Whip and the Body (1963), Kill, Baby, Kill (1966), and Baron Blood (1972). Boris Karloff's other films from 1963 include The Raven, The Terror, and The Comedy of Terrors, proving that the iconic star was still much in demand over forty years after his screen debut. You'll find Mark Damon in Corman's House of Usher (1960) and in later continental shockers like The Devil's Wedding Night (1973) and Hannah, Queen of the Vampires (1973). Michele Mercier is best remembered as the star of Angelique (1964) and its sequels, but she returns to the horror genre for Web of the Spider (1971).

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

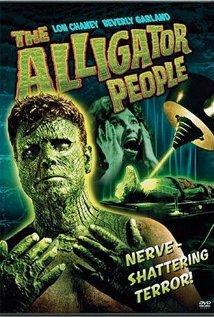

Classic Films in Focus: THE ALLIGATOR PEOPLE (1959)

Like The Fly (1958), The Alligator People (1959) merges science fiction and horror with a premise about dangerous experimentation gone horribly wrong, although in the second movie's case the combination of animal and human traits is intentional rather than tragically coincidental. Thus we get Richard Crane, as the increasingly reptilian victim of medical innovation, wandering the Louisiana swamps with one seriously bad case of gator face, while Beverly Garland chases after him as a dedicated wife who just won't take "no" for an answer. Most horror fans will come to The Alligator People for Lon Chaney, Jr., who plays a drunken villain, or for another example of the drive-in sci-fi chiller that flowered in the 1950s, but additional attractions can be found in the direction of Roy Del Ruth and performances from experienced players like Bruce Bennett, George Macready, and Frieda Inescort, each of whom helps to nudge the picture beyond mere B-movie spectacle.

Garland is the story's protagonist, a newly married nurse named Joyce Webster whose husband, Paul (Richard Crane), vanishes from a train on their honeymoon. Joyce tracks Paul to his family's plantation in the swamps, where she meets his mother, Mrs. Hawthorne (Frieda Inescort), who gives Joyce an icy welcome and tries to force her to leave. Determined to uncover the truth, Joyce stays until her mother-in-law and a local medical researcher, Dr. Sinclair (George Macready), reveal that Paul is suffering the side effects of a radical treatment for injuries he sustained in a plane crash during the war. Joyce joins their efforts to reverse Paul's transformation, but chaos erupts when a loutish plantation worker, Manon (Lon Chaney, Jr.), transfers his violent hatred for alligators to the alligator man.

The Alligator People is by no means a great film, and it often makes choices that are typical of its genre, but it also offers pleasant surprises. The pseudo-science of the central plot is wrapped in a strange psychological setup that presents Joyce, now known as Jane, as a victim of trauma induced amnesia as a result of her experience. Bruce Bennett appears in the frame scenes as one of two sexist doctors who can't stop mentioning how attractive the nurse is even as they use hypnosis to dredge up her horrible past. On the plus side, the frame tale serves a practical purpose in that it lets the audience know right away that this story won't end well for the alligator man or his bride, much as the opening of The Fly sets that story on its unbending course toward tragedy. The sexism also gets a much appreciated rebuke in the stalwart devotion of Joyce, who refuses to give up her search or abandon her husband once she sees his monstrous transformation. She even goes after him at the end, screaming not so much at his freakish appearance as his awful demise. Sure, his alligator head looks utterly fake, and we can even see the seams in his bodysuit, but Beverly Garland's performance as Joyce helps us focus on the drama of the situation rather than its special effects budget.

The success of the movie depends mostly on Garland, who plays Joyce as an active, intelligent woman caught up in overwhelming horror, but several supporting performances are worth noting. Lon Chaney. Jr. makes his presence felt as the belligerent Manon, a far nastier role than the actor's best known characters in other horror films. With his hook hand and his lecherous eye, Manon is a true monster; he provides a telling contrast to Paul, who loses the appearance of humanity but retains its inner qualities, even to the bitter end. Frieda Inescort also turns in a good performance as Paul's distraught mother; her accent wanders a bit, but she navigates the emotional territory of her character with greater assurance, letting her stern rejection of Joyce melt into shared misery over a loved one's terrible fate. Richard Crane gets less screen time as Paul, since he mostly skulks around the bayou in hiding, but his opening scenes set the stage for his later anguish. Hold on to the subtle cues on his handsome face as he talks about his accident with Joyce; that subtlety is lost later, but its emotional impact endures. Bruce Bennett and George Macready are both somewhat underused in their roles, but they give their doctors far more animation than such characters usually have in these pictures.

Some sci-fi B movies of this era are beloved precisely because they are campy and badly done, but The Alligator People takes a more serious tone, and despite its faults it's really a much better picture than it probably has any right to be. Give some of the credit for that to Roy Del Ruth, who also directed Born to Dance (1936), It Happened on Fifth Avenue (1947), and On Moonlight Bay (1951). See more of Beverly Garland in D.O.A. (1950), Not of This Earth (1957), and Twice-Told Tales (1963); she also enjoyed a long and varied television career and was even nominated for an Emmy. Lon Chaney, Jr. is best remembered for The Wolf Man (1941), but he plays supporting roles in many films, including The Black Castle (1952), The Black Sleep (1956), and The Haunted Palace (1963). Catch Frieda Inescort in Pride and Prejudice (1940), You'll Never Get Rich (1941), and The Return of the Vampire (1943). For similar 50s creature features, try I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), and Return of the Fly (1959).

Garland is the story's protagonist, a newly married nurse named Joyce Webster whose husband, Paul (Richard Crane), vanishes from a train on their honeymoon. Joyce tracks Paul to his family's plantation in the swamps, where she meets his mother, Mrs. Hawthorne (Frieda Inescort), who gives Joyce an icy welcome and tries to force her to leave. Determined to uncover the truth, Joyce stays until her mother-in-law and a local medical researcher, Dr. Sinclair (George Macready), reveal that Paul is suffering the side effects of a radical treatment for injuries he sustained in a plane crash during the war. Joyce joins their efforts to reverse Paul's transformation, but chaos erupts when a loutish plantation worker, Manon (Lon Chaney, Jr.), transfers his violent hatred for alligators to the alligator man.

The Alligator People is by no means a great film, and it often makes choices that are typical of its genre, but it also offers pleasant surprises. The pseudo-science of the central plot is wrapped in a strange psychological setup that presents Joyce, now known as Jane, as a victim of trauma induced amnesia as a result of her experience. Bruce Bennett appears in the frame scenes as one of two sexist doctors who can't stop mentioning how attractive the nurse is even as they use hypnosis to dredge up her horrible past. On the plus side, the frame tale serves a practical purpose in that it lets the audience know right away that this story won't end well for the alligator man or his bride, much as the opening of The Fly sets that story on its unbending course toward tragedy. The sexism also gets a much appreciated rebuke in the stalwart devotion of Joyce, who refuses to give up her search or abandon her husband once she sees his monstrous transformation. She even goes after him at the end, screaming not so much at his freakish appearance as his awful demise. Sure, his alligator head looks utterly fake, and we can even see the seams in his bodysuit, but Beverly Garland's performance as Joyce helps us focus on the drama of the situation rather than its special effects budget.

The success of the movie depends mostly on Garland, who plays Joyce as an active, intelligent woman caught up in overwhelming horror, but several supporting performances are worth noting. Lon Chaney. Jr. makes his presence felt as the belligerent Manon, a far nastier role than the actor's best known characters in other horror films. With his hook hand and his lecherous eye, Manon is a true monster; he provides a telling contrast to Paul, who loses the appearance of humanity but retains its inner qualities, even to the bitter end. Frieda Inescort also turns in a good performance as Paul's distraught mother; her accent wanders a bit, but she navigates the emotional territory of her character with greater assurance, letting her stern rejection of Joyce melt into shared misery over a loved one's terrible fate. Richard Crane gets less screen time as Paul, since he mostly skulks around the bayou in hiding, but his opening scenes set the stage for his later anguish. Hold on to the subtle cues on his handsome face as he talks about his accident with Joyce; that subtlety is lost later, but its emotional impact endures. Bruce Bennett and George Macready are both somewhat underused in their roles, but they give their doctors far more animation than such characters usually have in these pictures.

Some sci-fi B movies of this era are beloved precisely because they are campy and badly done, but The Alligator People takes a more serious tone, and despite its faults it's really a much better picture than it probably has any right to be. Give some of the credit for that to Roy Del Ruth, who also directed Born to Dance (1936), It Happened on Fifth Avenue (1947), and On Moonlight Bay (1951). See more of Beverly Garland in D.O.A. (1950), Not of This Earth (1957), and Twice-Told Tales (1963); she also enjoyed a long and varied television career and was even nominated for an Emmy. Lon Chaney, Jr. is best remembered for The Wolf Man (1941), but he plays supporting roles in many films, including The Black Castle (1952), The Black Sleep (1956), and The Haunted Palace (1963). Catch Frieda Inescort in Pride and Prejudice (1940), You'll Never Get Rich (1941), and The Return of the Vampire (1943). For similar 50s creature features, try I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), and Return of the Fly (1959).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)