Alfred Hitchcock called Shadow of a Doubt (1943) his favorite of his own pictures, and there's certainly a lot to appreciate in this smart, dark thriller about a young woman who suspects that her beloved uncle might not be what he seems. Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten give riveting performances as the two central characters, both called Charlie, who rightly claim that their relationship goes far beyond the typically avuncular. While much of the really daring subject matter remains in the subtext, Shadow of a Doubt stirs up quite a psychological hornet's nest with its conflicted young heroine and her charming but deadly relative, and for fans of character actors the film also delivers plum performances from Henry Travers and Hume Cronyn.

Wright plays the younger Charlie, who pines for something to shake up her family's boring routine in Santa Rosa, California. Her prayers seem to be answered when her Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) arrives for a rare visit, bearing gifts and smiles for everyone, but especially for Charlie and her mother, Emma (Patricia Collinge). Soon, however, young Charlie learns that her uncle is being pursued by two men who suspect him of committing terrible crimes, and Charlie herself begins to think that Uncle Charlie might actually be the Merry Widow Murderer for whom the police have been searching.

Young Charlie makes for an unusual Hitchcock protagonist if we think of the kinds of characters who take center stage in his most popular thrillers, where James Stewart and Cary Grant play very grown-up men embroiled in mystery and violence. Teresa Wright's heroine is, by contrast, not only female and innocent but also childlike in her initial view of the world and its inhabitants; in a modern remake Charlie might well be played by a fifteen year old, and the chaste romance with Detective Jack Graham (Macdonald Carey) could be dispensed with altogether. Despite her youth and girlish attitudes, Charlie proves to be a resourceful, strong-willed heroine, who has to confront her uncle on her own and then survive the consequences of knowing too much. Only Charlie manages to uncover the truth that eludes the police, and only Charlie can defend herself against her uncle's lethal intentions.When the climactic moment comes, nobody can save young Charlie but herself, and, in the end, she has to carry a burden of knowledge and sorrow that she rightly judges to be too much for her loving family.

In addition to its intriguing young heroine, the movie offers a mesmerizing study in duality. Two suspects elude the police, one in the west and one in the east. Two detectives pursue Uncle Charlie from place to place. Two train trips frame the action; one brings Uncle Charlie to town, and another carries him away. Most importantly, two Charlies stand at the center of the story, linked by blood but separated by it, too. Uncle Charlie is himself another example of duality, with one charming persona for company and a hidden, deadly side that he keeps secret at all costs. The extensive doubling also turns up with young Charlie's father (Henry Travers) and his friend, Herbie (Hume Cronyn), a strange pair of would-be murderers who constantly imagine ways to kill each other. Their macabre fantasies contrast with the real murder attempts taking place in the family's own home, but they never suspect a thing. Only Emma, Charlie's devoted older sister, ponders the significance of the two strange "accidents" that befall young Charlie and almost take her life. A subtler pairing occurs between Uncle Charlie and Detective Graham; both of them want young Charlie's loyalty and love, and it's only after the romance between the two young people flowers that Uncle Charlie turns violent. Does he view Graham as a romantic rival as well as a threat to his freedom? There's an incestuous undercurrent in the relationship between the two Charlies, hinted at and suggested in the ring that he gives her and the fact that he's sleeping in her bed. Think about it hard enough and Shadow of a Doubt more than lives up to its ominous name.

Gordon McDonell's original story for Shadow of a Doubt earned the movie its only Oscar nomination, but Teresa Wright had already won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress the previous year, for her performance in Mrs. Miniver (1942). The young actress also picked up nominations for The Little Foxes (1941) and The Pride of the Yankees (1942). Joseph Cotten is probably best remembered today for his performance in Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941), but he also stars in Gaslight (1944), Portrait of Jennie (1948), and The Third Man (1949). Shadow of a Doubt marks the screen debut of Hume Cronyn; see more of him in Lifeboat (1944), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), and Brute Force (1947). For more Hitchcock heroines, try Sabotage (1936), The Lady Vanishes (1938), and Rebecca (1940).

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

Classic Films in Focus: THE CREATURE WALKS AMONG US (1956)

What you make of The Creature Walks Among Us (1956) probably depends on how you feel about 1950s B horror and science fiction as well as the iconic monster himself. The third and final Gill Man picture revises the formula established in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) with a couple of odd twists, most notably an injury and subsequent radical experiments that make this movie's creature quite different from the original version. Many of the other elements remain the same, including the presumptuous scientists and some attractive female bait to get the Gill Man's attention, but these are standard equipment for scores of similar films from this era. Director John Sherwood takes over from Jack Arnold, who spearheaded the first two pictures, while Jeff Morrow, Rex Reason, and Leigh Snowden star, but, once again, the Gill Man is the most interesting character on screen, a tragic figure of alienation whose third encounter with human beings only brings him more suffering and pain.

Jeff Morrow leads the cast as Dr. William Barton, an obsessed scientist who finances a trip to capture and experiment on the Gill Man. Along for the journey are Barton's young wife, Marcia (Leigh Snowden), the brash Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer), and Barton's reluctant colleague, Dr. Thomas Morgan (Rex Reason), as well as a handful of other scientists and crew. When their capture of the creature results in his gills and scales being badly burned, the scientists trigger changes that make the Gill Man a more humanoid air breather, but they argue about the inherent violence of the creature's nature. Meanwhile, Barton's jealousy about his wife creates further tension between him and everyone else, especially when Jed pursues Marcia with boorish determination.

Like most of these pseudo-science B pictures, The Creature Walks Among Us gets off to a slow start, with lots of inane explanation and technical talk about aquatic life, genetics, and sonar. Things pick up as the human characters reveal their quirks, but the real action begins when the Gill Man makes his first appearance. The sluggish first act is more of a problem in a film that only runs 78 minutes, and it does seem like the third movie in a series, coming out so soon after the first two, could dispense with the exposition and get on with the monster mayhem. Actually, the monster doesn't even get to wreak that much havoc, since he's quickly captured, wrapped in bandages, and then imprisoned with a flock of sheep for company. He spends most of his time lying on an operating table or staring forlornly at the ocean from his cage. The cruel irony of a sea creature separated from his natural element generates a lot of pathos, but it eliminates much of the underwater action that made the original movie so interesting.

The creature is, at any rate, one of the film's more dynamic characters, since he undergoes both physical and psychological changes as a result of his experiences. He's very much a figure out of Frankenstein or The Island of Dr. Moreau, the violent but innocent victim of man's hubris. This particular installment does less with the Gill Man's usual preoccupation with the ladies, but it does draw parallels between his situation and that of Marcia, whom Barton also treats as an inferior possession. Barton, it turns out, is the real monster of the story; Jeff Morrow plays him with a creepy intensity that makes him the scariest the thing in the picture, especially in his confrontations with Marcia and Jed. Morgan, who is meant to be a humane foil to Barton, looks good in a swimsuit but has a less interesting role to play, and he goes along with the experiments too much to escape culpability. Of the humans, only Marcia is really exempt from blame, and the mixed depiction of her characters makes it hard to like her, especially when she insists on accompanying a diving expedition for no good reason and then promptly requires rescuing. The rest of the characters remain rooted in the background, providing some ostensibly necessary dialogue but never really contributing to the development of the narrative themes.

The Creature Walks Among Us is something of a weak finish to the Gill Man series, but there's enough going on here to warrant attention from fans of the genre or the monster. Be sure to see the original Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and Revenge of the Creature (1955) first to get the whole story. John Sherwood worked much more often as an assistant or second unit director, but he's also in the director's chair for The Monolith Monsters (1957). See Jeff Morrow and Rex Reason in This Island Earth (1955); you can also catch Morrow in Kronos (1957) and The Giant Claw (1957). You'll find Leigh Snowden in Kiss Me Deadly (1955) and a handful of B pictures like Hot Rod Rumble (1957).

Jeff Morrow leads the cast as Dr. William Barton, an obsessed scientist who finances a trip to capture and experiment on the Gill Man. Along for the journey are Barton's young wife, Marcia (Leigh Snowden), the brash Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer), and Barton's reluctant colleague, Dr. Thomas Morgan (Rex Reason), as well as a handful of other scientists and crew. When their capture of the creature results in his gills and scales being badly burned, the scientists trigger changes that make the Gill Man a more humanoid air breather, but they argue about the inherent violence of the creature's nature. Meanwhile, Barton's jealousy about his wife creates further tension between him and everyone else, especially when Jed pursues Marcia with boorish determination.

Like most of these pseudo-science B pictures, The Creature Walks Among Us gets off to a slow start, with lots of inane explanation and technical talk about aquatic life, genetics, and sonar. Things pick up as the human characters reveal their quirks, but the real action begins when the Gill Man makes his first appearance. The sluggish first act is more of a problem in a film that only runs 78 minutes, and it does seem like the third movie in a series, coming out so soon after the first two, could dispense with the exposition and get on with the monster mayhem. Actually, the monster doesn't even get to wreak that much havoc, since he's quickly captured, wrapped in bandages, and then imprisoned with a flock of sheep for company. He spends most of his time lying on an operating table or staring forlornly at the ocean from his cage. The cruel irony of a sea creature separated from his natural element generates a lot of pathos, but it eliminates much of the underwater action that made the original movie so interesting.

The creature is, at any rate, one of the film's more dynamic characters, since he undergoes both physical and psychological changes as a result of his experiences. He's very much a figure out of Frankenstein or The Island of Dr. Moreau, the violent but innocent victim of man's hubris. This particular installment does less with the Gill Man's usual preoccupation with the ladies, but it does draw parallels between his situation and that of Marcia, whom Barton also treats as an inferior possession. Barton, it turns out, is the real monster of the story; Jeff Morrow plays him with a creepy intensity that makes him the scariest the thing in the picture, especially in his confrontations with Marcia and Jed. Morgan, who is meant to be a humane foil to Barton, looks good in a swimsuit but has a less interesting role to play, and he goes along with the experiments too much to escape culpability. Of the humans, only Marcia is really exempt from blame, and the mixed depiction of her characters makes it hard to like her, especially when she insists on accompanying a diving expedition for no good reason and then promptly requires rescuing. The rest of the characters remain rooted in the background, providing some ostensibly necessary dialogue but never really contributing to the development of the narrative themes.

The Creature Walks Among Us is something of a weak finish to the Gill Man series, but there's enough going on here to warrant attention from fans of the genre or the monster. Be sure to see the original Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and Revenge of the Creature (1955) first to get the whole story. John Sherwood worked much more often as an assistant or second unit director, but he's also in the director's chair for The Monolith Monsters (1957). See Jeff Morrow and Rex Reason in This Island Earth (1955); you can also catch Morrow in Kronos (1957) and The Giant Claw (1957). You'll find Leigh Snowden in Kiss Me Deadly (1955) and a handful of B pictures like Hot Rod Rumble (1957).

Thursday, February 4, 2016

Films of 1947

Every year of the golden age of Hollywood produced worthy films, but certain years turned out bumper crops of great classic movies. 1939 immediately comes to mind, of course, but other years also turned out scores of timeless pictures that still enthrall audiences today. Whenever I'm working on a compilation of classic film reviews for my Beyond Casablanca books, I always find that 1947 is one of those years, offering an embarrassment of cinematic riches where the worthy contenders always outnumber the space I can devote to them. It's an especially good year for film noir, but excellent dramas and comedies also abound; you can thank 1947 for as diverse a selection as Out of the Past, Miracle on 34th Street, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, and The Egg and I. Since I can never get all the great 1947 films into a single book, here are the ones that I have, at least, posted reviews of here on Virtual Virago. Check out how many terrific pictures this one year produced!

BLACK NARCISSUS

BORN TO KILL

CROSSFIRE

DARK PASSAGE

THE GHOST AND MRS. MUIR

IT HAPPENED ON 5TH AVENUE

IT'S A JOKE, SON!

KISS OF DEATH

MIRACLE ON 34TH STREET

NIGHTMARE ALLEY

THE UNSUSPECTED

Here are the 1947 films that I review in Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching (which you can get for just 99 cents on Amazon Kindle, if you're so inclined).

THE EGG AND I

THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI

OUT OF THE PAST

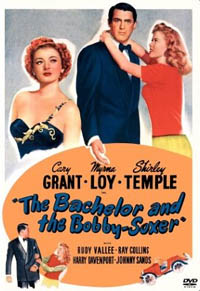

The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer is the sole representative of the year in Beyond Casablanca II: 101 Classic Movies Worth Watching (also 99 cents on Amazon Kindle). I had to make tough choices for that one to have room for films from the early 1960s, and the triple threat of Cary Grant, Shirley Temple, and Myrna Loy made it a choice that covered a lot of cinematic ground. It's also wonderfully funny and less familiar to many viewers than Grant's signature films.

But wait, there's more! Here are some other memorable films from 1947 that I haven't gotten around to writing about yet. This is just a partial list, but clearly there is work to be done.

ANGEL AND THE BADMAN

THE BISHOP'S WIFE

BRUTE FORCE

DAISY KENYON

DEAD RECKONING

A DOUBLE LIFE

FOREVER AMBER

GENTLEMAN'S AGREEMENT

POSSESSED

What's your favorite film from 1947? If you had to pick just three to include in a book, which ones would you choose? I'll be thinking about that question myself as I work on my next book-length compilation of reviews.

BLACK NARCISSUS

BORN TO KILL

CROSSFIRE

DARK PASSAGE

THE GHOST AND MRS. MUIR

IT HAPPENED ON 5TH AVENUE

IT'S A JOKE, SON!

KISS OF DEATH

MIRACLE ON 34TH STREET

NIGHTMARE ALLEY

THE UNSUSPECTED

Here are the 1947 films that I review in Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching (which you can get for just 99 cents on Amazon Kindle, if you're so inclined).

THE EGG AND I

THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI

OUT OF THE PAST

The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer is the sole representative of the year in Beyond Casablanca II: 101 Classic Movies Worth Watching (also 99 cents on Amazon Kindle). I had to make tough choices for that one to have room for films from the early 1960s, and the triple threat of Cary Grant, Shirley Temple, and Myrna Loy made it a choice that covered a lot of cinematic ground. It's also wonderfully funny and less familiar to many viewers than Grant's signature films.

But wait, there's more! Here are some other memorable films from 1947 that I haven't gotten around to writing about yet. This is just a partial list, but clearly there is work to be done.

ANGEL AND THE BADMAN

THE BISHOP'S WIFE

BRUTE FORCE

DAISY KENYON

DEAD RECKONING

A DOUBLE LIFE

FOREVER AMBER

GENTLEMAN'S AGREEMENT

POSSESSED

What's your favorite film from 1947? If you had to pick just three to include in a book, which ones would you choose? I'll be thinking about that question myself as I work on my next book-length compilation of reviews.

Classic Films in Focus: MIRACLE ON 34TH STREET (1947)

Although it has been remade several times, the original 1947 release of Miracle on 34th Street is still the best and most charming incarnation of this heart-warming tale of holiday faith. Its attractions include an Oscar-winning Santa Claus performance courtesy of Edmund Gwenn and a memorable early appearance from a very young Natalie Wood, as well as lovely Maureen O’Hara and the very likable John Payne as the romantic leads. With its three Oscar wins and its enduring appeal, Miracle on 34th Street thoroughly deserves its status as a holiday classic, one of those movies that it just wouldn’t be Christmas without.

The story opens at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, where Macy’s employee Doris Walker (Maureen O’Hara) recruits a singular Santa (Edmund Gwenn) as a last-minute replacement. Soon the kindly Kris Kringle is working at the store, where he delights customers and their children but alarms Doris by insisting that he really is Santa Claus. When Kris’ sanity is called into question, Doris’ handsome neighbor (John Payne) comes to his defense in court.

The love story between O’Hara and Payne works perfectly well, but the movie is really more interested in Kris Kringle and little Susan (Natalie Wood), Doris’ skeptical daughter. Their scenes together burst with sentimental feeling and gentle good humor as they pretend to be monkeys, blow bubble gum, and gradually build a relationship despite Susan’s doubts. For many people, Gwenn’s Kris is the quintessential Santa Claus, generous and droll with just a hint of mischief in his twinkling eyes. The story leaves it up to the viewer to decide if Kris really is the jolly old elf, but, as the Magic 8 Ball would say, “Signs point to yes.”

Behind the holiday cheer lie some serious themes, including Doris’ loss of faith following the end of her marriage to Susan’s father. Susan clearly yearns for a paternal figure, as her friendship with the neighborly Fred makes clear, but she’s also incomplete because her mother has discouraged her from believing in anything or even using her imagination. Fred and Kris must work together to heal this broken little family, an accomplishment perfectly symbolized by the film’s closing scene. Like most of the very best Christmas movies, this one balances its sweetness with melancholy and the bitterness of experience, and the spirit of Christmas is as much about acknowledging those feelings as it is about merriment and goodwill.

Director George Seaton had his other big directorial success with The Country Girl (1954), but he wrote twice as many screenplays as he directed. Maureen O’Hara can be found in How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Black Swan (1942), and The Quiet Man (1952). Look for John Payne in The Razor’s Edge (1946) and Kansas City Confidential (1952). Edmund Gwenn also stars in Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Pride and Prejudice (1940), and Them! (1954). See a more grown-up Natalie Wood in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), The Searchers (1956), and West Side Story (1961). Don’t miss memorable character actress Thelma Ritter in a brief, uncredited role as a mother who speaks to Santa.

The story opens at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, where Macy’s employee Doris Walker (Maureen O’Hara) recruits a singular Santa (Edmund Gwenn) as a last-minute replacement. Soon the kindly Kris Kringle is working at the store, where he delights customers and their children but alarms Doris by insisting that he really is Santa Claus. When Kris’ sanity is called into question, Doris’ handsome neighbor (John Payne) comes to his defense in court.

The love story between O’Hara and Payne works perfectly well, but the movie is really more interested in Kris Kringle and little Susan (Natalie Wood), Doris’ skeptical daughter. Their scenes together burst with sentimental feeling and gentle good humor as they pretend to be monkeys, blow bubble gum, and gradually build a relationship despite Susan’s doubts. For many people, Gwenn’s Kris is the quintessential Santa Claus, generous and droll with just a hint of mischief in his twinkling eyes. The story leaves it up to the viewer to decide if Kris really is the jolly old elf, but, as the Magic 8 Ball would say, “Signs point to yes.”

Behind the holiday cheer lie some serious themes, including Doris’ loss of faith following the end of her marriage to Susan’s father. Susan clearly yearns for a paternal figure, as her friendship with the neighborly Fred makes clear, but she’s also incomplete because her mother has discouraged her from believing in anything or even using her imagination. Fred and Kris must work together to heal this broken little family, an accomplishment perfectly symbolized by the film’s closing scene. Like most of the very best Christmas movies, this one balances its sweetness with melancholy and the bitterness of experience, and the spirit of Christmas is as much about acknowledging those feelings as it is about merriment and goodwill.

Director George Seaton had his other big directorial success with The Country Girl (1954), but he wrote twice as many screenplays as he directed. Maureen O’Hara can be found in How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Black Swan (1942), and The Quiet Man (1952). Look for John Payne in The Razor’s Edge (1946) and Kansas City Confidential (1952). Edmund Gwenn also stars in Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Pride and Prejudice (1940), and Them! (1954). See a more grown-up Natalie Wood in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), The Searchers (1956), and West Side Story (1961). Don’t miss memorable character actress Thelma Ritter in a brief, uncredited role as a mother who speaks to Santa.

Monday, February 1, 2016

Classic Films in Focus: THE DAMNED DON'T CRY (1950)

Like Mildred Pierce (1945), The Damned Don't Cry (1950) stars Joan Crawford in a story that merges the themes of melodrama and film noir. Crawford is perfectly at home in both genres, and the combination of the two had revitalized her career with Mildred Pierce, for which she won her only Best Actress Oscar. Not surprisingly, then, The Damned Don't Cry offers Crawford a juicy role for which her talents are ideally suited. Despite the title, there's actually a fair bit of crying, especially on the part of Crawford's character, an unhappy housewife who trades ethics and poverty for a chance at getting more out of the rigged game of life. Solid direction from Vincent Sherman and a particularly good performance by Kent Smith help Crawford shine, while the story offers an opportunity to consider the femme fatale as a dynamic character who doesn't necessarily set out to ruin the men whose lives she inevitably destroys.

Crawford plays working-class housewife Ethel Whitehead, who walks out on her family after a devastating tragedy, determined to have something more for herself. She finds work but quickly realizes that she can get ahead by using her sexuality as an asset, especially in the shady world of gambling dens and nightclubs. She seduces a mild but intelligent accountant, Martin Blankford (Kent Smith), and talks him into a job with a criminal organization, but by the time Martin proposes Ethel has already hooked a bigger fish, the kingpin George Castleman (David Brian). Castleman remakes Ethel into widowed oil heiress Lorna Hansen Forbes and provides her with a life of luxury, but it comes at a galling cost. The crime boss orders Lorna to head for Palm Springs and seduce a rebellious underling, Nick (Steve Cochran), so that George can find out how far Nick's treachery goes.

The Damned Don't Cry alternates between its two genres but achieves a balance that keeps the story interesting and constantly moving. The opening presents us with Nick's murder and Lorna's disappearance; it then moves backward to tell us how these characters reached that tragic climax. The violence of the first scene assures us that this story will be a gritty gangster tale as well as a women's melodrama, in spite of the long stretch that then unfolds Ethel's sad history and her first steps into a life of crime. Once George Castleman arrives on the scene, the story kicks up the noir heat; Ethel succumbs to greed and selfishness even as her actions doom the essentially decent Martin to life without his self-esteem or the woman for whom he gave it up. Everywhere she goes, Ethel brings misery to the men around her, even when she doesn't intend to do so. She abandons her husband, delivers clients to a shady casino, destroys Martin's respectability, betrays Nick, and even ends up being the ruin of Castleman. Crawford never plays Ethel as consciously evil; she can be hard, she can be determined, and she can be terribly selfish, but she has enough humanity to draw back from being involved in the murder of a man who has fallen in love with her. Unfortunately for her and everyone else, she changes course too late, but that's noir in a nutshell.

Two supporting performances stand out among the rest of the cast and help Crawford develop the complexities of her own character. Kent Smith, an actor who never quite became a star, has the best of the male roles as Martin. In a more conventional noir film Martin might be the protagonist, the good guy who falls into the abyss thanks to an ambitious woman. When we first meet him he's a real straight arrow, but over the course of the story he becomes jaded and hard; eventually he's the one pushing Ethel instead of the other way around. Martin never stops loving Ethel, as the final scenes make clear, but the life they might have had together is gone for good. Selena Royle has the other significant supporting role as Ethel's mentor and confidante, Patricia Longworth. The relationship between Ethel and Patricia is unusual; rarely do women in noir films trust each other and work together, but Patricia helps Ethel assume the worldly polish and glamour that being Lorna requires without ever seeming jealous of her or more loyal to Castleman than she is to Ethel. Ethel and Patricia collaborate so well that they can communicate volumes to each other with mere glances; they work like a pair of dancers or predators as they maneuver Nick into Ethel's arms. Royle plays her part with a subtle, quiet genius; she never upstages Crawford, but she makes her presence integral to the success of the picture. David Brian and Steve Cochran are both solid as the gangsters, one refined and the other reckless, but their characters are fairly straightforward. Cochran does, however, help us get past our initial dismissal of Nick to see why Ethel balks at betraying him, and Brian turns up the brutality for a shocking confrontation near the picture's end.

After The Damned Don't Cry, Joan Crawford and Vincent Sherman also made Harriet Craig (1950) and Goodbye, My Fancy (1951). You can compare the leading lady's work on this film with other memorable performances in A Woman's Face (1941), Torch Song (1953) and Johnny Guitar (1954), all of which feature tough, complex heroines. Kent Smith is best remembered today as the clueless husband in Cat People (1942), but he also appears in The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Spiral Staircase (1945). Look for Selena Royle in supporting roles in The Harvey Girls (1946), A Date with Judy (1948), and The Heiress (1949). David Brian stars with Crawford in Flamingo Road (1949) and This Woman is Dangerous (1952), but his greatest critical success came with Intruder in the Dust (1949), which earned Brian a Golden Globe nomination. See Steve Cochran as a series of unsavory characters in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), White Heat (1949), and Storm Warning (1951).

Crawford plays working-class housewife Ethel Whitehead, who walks out on her family after a devastating tragedy, determined to have something more for herself. She finds work but quickly realizes that she can get ahead by using her sexuality as an asset, especially in the shady world of gambling dens and nightclubs. She seduces a mild but intelligent accountant, Martin Blankford (Kent Smith), and talks him into a job with a criminal organization, but by the time Martin proposes Ethel has already hooked a bigger fish, the kingpin George Castleman (David Brian). Castleman remakes Ethel into widowed oil heiress Lorna Hansen Forbes and provides her with a life of luxury, but it comes at a galling cost. The crime boss orders Lorna to head for Palm Springs and seduce a rebellious underling, Nick (Steve Cochran), so that George can find out how far Nick's treachery goes.

The Damned Don't Cry alternates between its two genres but achieves a balance that keeps the story interesting and constantly moving. The opening presents us with Nick's murder and Lorna's disappearance; it then moves backward to tell us how these characters reached that tragic climax. The violence of the first scene assures us that this story will be a gritty gangster tale as well as a women's melodrama, in spite of the long stretch that then unfolds Ethel's sad history and her first steps into a life of crime. Once George Castleman arrives on the scene, the story kicks up the noir heat; Ethel succumbs to greed and selfishness even as her actions doom the essentially decent Martin to life without his self-esteem or the woman for whom he gave it up. Everywhere she goes, Ethel brings misery to the men around her, even when she doesn't intend to do so. She abandons her husband, delivers clients to a shady casino, destroys Martin's respectability, betrays Nick, and even ends up being the ruin of Castleman. Crawford never plays Ethel as consciously evil; she can be hard, she can be determined, and she can be terribly selfish, but she has enough humanity to draw back from being involved in the murder of a man who has fallen in love with her. Unfortunately for her and everyone else, she changes course too late, but that's noir in a nutshell.

Two supporting performances stand out among the rest of the cast and help Crawford develop the complexities of her own character. Kent Smith, an actor who never quite became a star, has the best of the male roles as Martin. In a more conventional noir film Martin might be the protagonist, the good guy who falls into the abyss thanks to an ambitious woman. When we first meet him he's a real straight arrow, but over the course of the story he becomes jaded and hard; eventually he's the one pushing Ethel instead of the other way around. Martin never stops loving Ethel, as the final scenes make clear, but the life they might have had together is gone for good. Selena Royle has the other significant supporting role as Ethel's mentor and confidante, Patricia Longworth. The relationship between Ethel and Patricia is unusual; rarely do women in noir films trust each other and work together, but Patricia helps Ethel assume the worldly polish and glamour that being Lorna requires without ever seeming jealous of her or more loyal to Castleman than she is to Ethel. Ethel and Patricia collaborate so well that they can communicate volumes to each other with mere glances; they work like a pair of dancers or predators as they maneuver Nick into Ethel's arms. Royle plays her part with a subtle, quiet genius; she never upstages Crawford, but she makes her presence integral to the success of the picture. David Brian and Steve Cochran are both solid as the gangsters, one refined and the other reckless, but their characters are fairly straightforward. Cochran does, however, help us get past our initial dismissal of Nick to see why Ethel balks at betraying him, and Brian turns up the brutality for a shocking confrontation near the picture's end.

After The Damned Don't Cry, Joan Crawford and Vincent Sherman also made Harriet Craig (1950) and Goodbye, My Fancy (1951). You can compare the leading lady's work on this film with other memorable performances in A Woman's Face (1941), Torch Song (1953) and Johnny Guitar (1954), all of which feature tough, complex heroines. Kent Smith is best remembered today as the clueless husband in Cat People (1942), but he also appears in The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Spiral Staircase (1945). Look for Selena Royle in supporting roles in The Harvey Girls (1946), A Date with Judy (1948), and The Heiress (1949). David Brian stars with Crawford in Flamingo Road (1949) and This Woman is Dangerous (1952), but his greatest critical success came with Intruder in the Dust (1949), which earned Brian a Golden Globe nomination. See Steve Cochran as a series of unsavory characters in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), White Heat (1949), and Storm Warning (1951).