Tyrone Power is best remembered today as a swashbuckling hero, but in Nightmare Alley (1947) the star gets to revel in his darker side, using his good looks and intense charisma to chilling effect as a callous heel whose con games inevitably catch up with him. Directed by Edmund Goulding, this classic film noir bursts with shady characters and seedy ambiance; no setting could be better suited to the fatalistic shadow play of the genre than a two-bit traveling carnival, with its losers, crooks, and abject sideshow freaks. Joan Blondell, Coleen Gray, and Helen Walker give solid performances as the trio of women who shape Power’s protagonist, but it’s Power himself who dominates the show in a role he truly was made for.

Power plays ambitious carny Stan Carlisle, who hopes to become a big time performer with the help of middle-aged mentalist Zeena (Joan Blondell). When Zeena’s alcoholic husband dies, she gives Stan the break he wants, but Stan uses the opportunity to quit the carnival and take his naive young bride, Molly (Coleen Gray), with him. Stan’s fame and fortune rise, but he courts disaster when he falls in with a beautiful psychologist (Helen Walker) who encourages him to begin a dangerously complicated con.

Power gives an electrifying performance as Stan. His handsome features here take on a dissipated edge, with crow’s feet crinkling around his hungry, burning eyes. We know from the start that Stan is no good, but Power makes him more anti-hero than true villain, a small-time guy whose ambition is always too big for him. Stan uses everyone he meets, especially the women, but he surprises us and perhaps himself, as well, when it turns out that he really does love Molly. His young wife’s refusal to carry out his cynical deception is not a betrayal of Stan but an expression of her own innate goodness; we expect him to be furious with her, but instead he rushes to get her out of harm’s way, leading to a brief, tender moment of farewell. In many noir films, a good girl like Molly can be as much the protagonist’s undoing as the femme fatale, but the final scene suggests that in this case Molly might yet be Stan’s saving grace. Power’s character walks a fine enough moral line that we want to see that glimmer of hope at the end, even as we relish Stan’s much-deserved fall.

Noir generally deals in the workings of fate, but in Nightmare Alley the theme has special significance. The turning of Fortune’s wheel is represented as inevitable, irresistible, and grimly ironic. When we first meet Stan we find him both fascinated and horrified by the carnival geek, a poor sap fallen so low that he’ll bite the heads off of live chickens for a bottle of booze and a place to sleep. Throughout the film, Stan’s moments of crisis are punctuated by the remembered screams of the geek; we know, as Stan himself does, that this fate waits for him as surely as death waits for us all. Zeena’s Tarot cards confirm that Stan must take his place as the hanged man, the heir to Zeena’s doomed husband and the geek, as well. In the world of carnival noir, the characters’ belief in Tarot is never merely superstition; the cards reveal the truth about a world controlled by fate. Only a fool like Stan tries to fight it. His last line in the film, “Mister, I was made for it,” is both an ironic echo of his earlier ego and a signal that Stan finally accepts the card he has been dealt.

In addition to the major players, be sure to appreciate the distinctive presence of Mike Mazurki as the carnival strongman, Bruno. Tyrone Power is best known for films like The Mark of Zorro (1940) and The Black Swan (1942), but he also plays a darker character in his final picture, Witness for the Prosecution (1957). Sample Joan Blondell’s long career with Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), and Desk Set (1957). Look for Coleen Gray in Kiss of Death (1947), Red River (1948), and Kansas City Confidential (1952). Helen Walker also stars in Brewster’s Millions (1945), Murder, He Says (1945), and Call Northside 777 (1948). For more from director Edmund Goulding, see Grand Hotel (1932), Dark Victory (1939), and The Razor’s Edge (1946).

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Monday, April 28, 2014

Classic Films in Focus: BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936 (1935)

The second in a series of movies that began with The Broadway Melody (1929), The Broadway Melody of 1936 (1935) depends on a familiar combination of thin show business plot and upbeat musical numbers, both elements that reliably appealed to Depression Era audiences. For many modern viewers, these lightweight entertainments might seem unbearably corny and naive, but their cheerful reliance on pluck and stardust makes them great antidotes to the rainy day blues. The Broadway Melody of 1936 has particular appeal for fans of the very talented Eleanor Powell, a favorite among musical devotees, but it also offers fun performances from beloved stars like Robert Taylor, Jack Benny, and Una Merkel, as well as the screen debut of a strikingly young - and limber - Buddy Ebsen.

Jack Benny plays gossip columnist Bert Keeler, whose boss orders him to give up blessed event stories for juicier celebrity tattle. Keeler goes after Broadway producer Bob Gordon (Robert Taylor) and his wealthy socialite investor, Lillian Brent (June Knight), which starts a feud between the two men. Meanwhile, Bob’s hometown high school sweetheart, Irene (Eleanor Powell), arrives in New York hoping to break into show business. Bob refuses to support Irene’s aspirations, but Keeler’s wild scheme to make a mockery of Bob gives Irene an unexpected chance to change his mind.

The story begins with two seemingly distinct elements, connected by their relationship to Taylor’s character, with Jack Benny running a slapstick comedy and Eleanor Powell doing a Ruby Keeler new kid in town routine with heavy romantic undertones. The surprise comes when Powell jumps enthusiastically into Benny’s territory and turns the last third of the narrative into a screwball comedy; her scenes as the fictitious Mademoiselle Arlette, complete with outrageous French accent, are really very funny, and she certainly looks better in the blonde wig than Benny’s long-suffering sidekick, Sid Silvers. Adding to the picture’s comedic bent are Una Merkel as Gordon’s sharp-witted secretary and Buddy Ebsen as a young hoofer who becomes one of Irene’s new friends. Ebsen’s real life sister, Vilma, makes her one and only screen appearance as the sister of his character.

The musical numbers, written by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed, are the movie’s highlights, especially when Eleanor Powell’s fantastic tap dancing accompanies them. Fans of Singin’ in the Rain (1952) will recognize “You Are My Lucky Star” and “Broadway Rhythm,” both of which are prominently featured in this earlier film. Buddy and Vilma Ebsen perform the charming “Sing Before Breakfast” number as well as a later song that is part of Bob Gordon’s show, and in both segments Ebsen gets to demonstrate the distinctively comic style of his dancing technique. Ebsen was 27 when he made the movie, but he looks like such a kid in his Mickey Mouse sweater that it’s hard to recognize him as the future Jed Clampett and Barnaby Jones. Popular singer and actress Frances Langford appears in the movie as herself and performs “I’ve Got a Feelin’ You’re Foolin’” as well as several other songs.

Broadway Melody of 1936 won an Oscar for Best Dance Direction and scored additional nominations for Best Picture and Best Original Story. Its director, Roy Del Ruth, also worked with Eleanor Powell and Buddy Ebsen on Born to Dance (1936) and Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937). For more of the glorious Eleanor Powell, see Honolulu (1939), Broadway Melody of 1940 (1940), and Lady Be Good (1941). You’ll find Robert Taylor in A Yank at Oxford (1938), Waterloo Bridge (1940), and Ivanhoe (1952). Jack Benny provides more laughs in Charley’s Aunt (1941) and To Be or Not to Be (1942), while Una Merkel, a veteran of the Pre-Code Era and a terrific comedienne, gives an especially hilarious performance in Destry Rides Again (1939). For more of Buddy Ebsen’s varied career, check out his movies with cowboy star Rex Allen, including Silver City Bonanza (1951) and Utah Wagon Train (1951).

Broadway Melody of 1936 is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant, along with several other Eleanor Powell pictures.

Jack Benny plays gossip columnist Bert Keeler, whose boss orders him to give up blessed event stories for juicier celebrity tattle. Keeler goes after Broadway producer Bob Gordon (Robert Taylor) and his wealthy socialite investor, Lillian Brent (June Knight), which starts a feud between the two men. Meanwhile, Bob’s hometown high school sweetheart, Irene (Eleanor Powell), arrives in New York hoping to break into show business. Bob refuses to support Irene’s aspirations, but Keeler’s wild scheme to make a mockery of Bob gives Irene an unexpected chance to change his mind.

The story begins with two seemingly distinct elements, connected by their relationship to Taylor’s character, with Jack Benny running a slapstick comedy and Eleanor Powell doing a Ruby Keeler new kid in town routine with heavy romantic undertones. The surprise comes when Powell jumps enthusiastically into Benny’s territory and turns the last third of the narrative into a screwball comedy; her scenes as the fictitious Mademoiselle Arlette, complete with outrageous French accent, are really very funny, and she certainly looks better in the blonde wig than Benny’s long-suffering sidekick, Sid Silvers. Adding to the picture’s comedic bent are Una Merkel as Gordon’s sharp-witted secretary and Buddy Ebsen as a young hoofer who becomes one of Irene’s new friends. Ebsen’s real life sister, Vilma, makes her one and only screen appearance as the sister of his character.

The musical numbers, written by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed, are the movie’s highlights, especially when Eleanor Powell’s fantastic tap dancing accompanies them. Fans of Singin’ in the Rain (1952) will recognize “You Are My Lucky Star” and “Broadway Rhythm,” both of which are prominently featured in this earlier film. Buddy and Vilma Ebsen perform the charming “Sing Before Breakfast” number as well as a later song that is part of Bob Gordon’s show, and in both segments Ebsen gets to demonstrate the distinctively comic style of his dancing technique. Ebsen was 27 when he made the movie, but he looks like such a kid in his Mickey Mouse sweater that it’s hard to recognize him as the future Jed Clampett and Barnaby Jones. Popular singer and actress Frances Langford appears in the movie as herself and performs “I’ve Got a Feelin’ You’re Foolin’” as well as several other songs.

Broadway Melody of 1936 won an Oscar for Best Dance Direction and scored additional nominations for Best Picture and Best Original Story. Its director, Roy Del Ruth, also worked with Eleanor Powell and Buddy Ebsen on Born to Dance (1936) and Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937). For more of the glorious Eleanor Powell, see Honolulu (1939), Broadway Melody of 1940 (1940), and Lady Be Good (1941). You’ll find Robert Taylor in A Yank at Oxford (1938), Waterloo Bridge (1940), and Ivanhoe (1952). Jack Benny provides more laughs in Charley’s Aunt (1941) and To Be or Not to Be (1942), while Una Merkel, a veteran of the Pre-Code Era and a terrific comedienne, gives an especially hilarious performance in Destry Rides Again (1939). For more of Buddy Ebsen’s varied career, check out his movies with cowboy star Rex Allen, including Silver City Bonanza (1951) and Utah Wagon Train (1951).

Broadway Melody of 1936 is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant, along with several other Eleanor Powell pictures.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

The Funniest Movies Ever Made

Inspired by David Misch's Funny: The Book, I asked people on Facebook and Twitter to name their favorite funny movies. I wanted to know which movies made them laugh the most, and I was hoping to get some interesting responses. What I ended up with was a list of some 70 films - almost enough for a book on the subject! - that covered a wide range of decades and comedy styles, although some real winners stood out in the final tally. Here are the top ten replies, in order of popularity.

1-2 Tied: BLAZING SADDLES (1974) and RAISING ARIZONA (1987)

These are both extremely funny movies, although the Nicholas Cage comedy, written and directed by the Coen brothers, is the less outrageous of the two. I expected Mel Brooks to end up in a high position on the list, so BLAZING SADDLES came as no surprise, but RAISING ARIZONA was not one that I would have bet on as a top contender. The Mel Brooks movie falls into the broader definition of a "classic," but I'm not so sure about the Coen brothers comedy, even though at this point it is more than 25 years old. It is, however, memorably funny, especially because of Holly Hunter's performance and the Coens' hilarious writing.

3-6 Tied: BRINGING UP BABY (1938), YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974), THE PALM BEACH STORY (1942), and IT'S A MAD, MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD (1963)

Yes, it's a four way tie for the rest of the top half, with some surprisingly retro choices from the Facebook crowd (maybe I have been a good influence on them!). BRINGING UP BABY is one of my all-time favorite movies, so I was glad to see it make the cut, and YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN continues to prove the popularity of Mel Brooks as a comedy king. Both of those would be on my own top ten list. I didn't expect to see THE PALM BEACH STORY make such a strong showing; it's chaotically funny, but my personal pick from the Preston Sturges canon would be THE MIRACLE OF MORGAN'S CREEK (1944). I was shocked that so many people would not only sit through but enjoy all 192 minutes of IT'S A MAD, MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD, but people who responded said that they loved the huge cast of classic stars.

7-10/11 Tied: DUCK SOUP (1933), NATIONAL LAMPOON'S CHRISTMAS VACATION (1989), ANIMAL HOUSE (1978), THE BIRDCAGE (1996), THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998)

The bottom third really gets into different territory, with only DUCK SOUP making my personal list of top comedies (several people generalized by saying "any Marx Brothers movie" as their choice). Here the generational bias of the responders shows through the most clearly, with more recent movies getting a lot of support. THE BIRDCAGE is the surprise finisher of this group, but it is very funny, and I love Hank Azaria's performance in particular. While I wasn't that shocked to see cult favorite THE BIG LEBOWSKI get votes, I personally can't stand it.

(several people generalized by saying "any Marx Brothers movie" as their choice). Here the generational bias of the responders shows through the most clearly, with more recent movies getting a lot of support. THE BIRDCAGE is the surprise finisher of this group, but it is very funny, and I love Hank Azaria's performance in particular. While I wasn't that shocked to see cult favorite THE BIG LEBOWSKI get votes, I personally can't stand it.

Honorable Mentions: MY FELLOW AMERICANS (1996), THE NAKED GUN (1988), O BROTHER, WHERE ART THOU? (2000), DUMB AND DUMBER (1994), L.A. STORY (1991), GROUNDHOG DAY (1993), THE PRODUCERS (1967), DR. STRANGELOVE (1964), AIRPLANE! (1980), MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (1975), THE APARTMENT (1960)

Honorable mentions are movies that at least two people chose, and this set shows the breadth of selections really opening up. Most of these are more recent films, with THE APARTMENT sneaking in as a surprise pick. Almost all of these movies pass my personal comedy test, except for DUMB AND DUMBER (its name pretty much sums up what I don't like about it). My favorites of this group would have to be O BROTHER and GROUNDHOG DAY, both of which make me laugh every time I watch them. I like a good story as the backdrop for the laughs, so I'm giving those two the edge over HOLY GRAIL and AIRPLANE!, even though I can recite most of the gags from both of them.

This, of course, is by no means a scientific survey. Technically, I asked over 2000 people between my Facebook and Twitter accounts. The Facebook crowd, ironically, responded more enthusiastically, even though on Facebook I am mostly connected to people I know in real life who may or may not be that into movies. On Twitter, where most of my active connections actually are movie bloggers and classic film fans, I got a lot fewer replies. Too much noise in the system there, I guess, compared to the 400+ people on Facebook.

Have you seen every movie that made the top ten list? What is your favorite funny movie? Let me know in the comments! If you're interested in learning more about David Misch's book, you can read my review of it here.

1-2 Tied: BLAZING SADDLES (1974) and RAISING ARIZONA (1987)

These are both extremely funny movies, although the Nicholas Cage comedy, written and directed by the Coen brothers, is the less outrageous of the two. I expected Mel Brooks to end up in a high position on the list, so BLAZING SADDLES came as no surprise, but RAISING ARIZONA was not one that I would have bet on as a top contender. The Mel Brooks movie falls into the broader definition of a "classic," but I'm not so sure about the Coen brothers comedy, even though at this point it is more than 25 years old. It is, however, memorably funny, especially because of Holly Hunter's performance and the Coens' hilarious writing.

3-6 Tied: BRINGING UP BABY (1938), YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974), THE PALM BEACH STORY (1942), and IT'S A MAD, MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD (1963)

Yes, it's a four way tie for the rest of the top half, with some surprisingly retro choices from the Facebook crowd (maybe I have been a good influence on them!). BRINGING UP BABY is one of my all-time favorite movies, so I was glad to see it make the cut, and YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN continues to prove the popularity of Mel Brooks as a comedy king. Both of those would be on my own top ten list. I didn't expect to see THE PALM BEACH STORY make such a strong showing; it's chaotically funny, but my personal pick from the Preston Sturges canon would be THE MIRACLE OF MORGAN'S CREEK (1944). I was shocked that so many people would not only sit through but enjoy all 192 minutes of IT'S A MAD, MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD, but people who responded said that they loved the huge cast of classic stars.

7-10/11 Tied: DUCK SOUP (1933), NATIONAL LAMPOON'S CHRISTMAS VACATION (1989), ANIMAL HOUSE (1978), THE BIRDCAGE (1996), THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998)

The bottom third really gets into different territory, with only DUCK SOUP making my personal list of top comedies

(several people generalized by saying "any Marx Brothers movie" as their choice). Here the generational bias of the responders shows through the most clearly, with more recent movies getting a lot of support. THE BIRDCAGE is the surprise finisher of this group, but it is very funny, and I love Hank Azaria's performance in particular. While I wasn't that shocked to see cult favorite THE BIG LEBOWSKI get votes, I personally can't stand it.

(several people generalized by saying "any Marx Brothers movie" as their choice). Here the generational bias of the responders shows through the most clearly, with more recent movies getting a lot of support. THE BIRDCAGE is the surprise finisher of this group, but it is very funny, and I love Hank Azaria's performance in particular. While I wasn't that shocked to see cult favorite THE BIG LEBOWSKI get votes, I personally can't stand it.Honorable Mentions: MY FELLOW AMERICANS (1996), THE NAKED GUN (1988), O BROTHER, WHERE ART THOU? (2000), DUMB AND DUMBER (1994), L.A. STORY (1991), GROUNDHOG DAY (1993), THE PRODUCERS (1967), DR. STRANGELOVE (1964), AIRPLANE! (1980), MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (1975), THE APARTMENT (1960)

Honorable mentions are movies that at least two people chose, and this set shows the breadth of selections really opening up. Most of these are more recent films, with THE APARTMENT sneaking in as a surprise pick. Almost all of these movies pass my personal comedy test, except for DUMB AND DUMBER (its name pretty much sums up what I don't like about it). My favorites of this group would have to be O BROTHER and GROUNDHOG DAY, both of which make me laugh every time I watch them. I like a good story as the backdrop for the laughs, so I'm giving those two the edge over HOLY GRAIL and AIRPLANE!, even though I can recite most of the gags from both of them.

This, of course, is by no means a scientific survey. Technically, I asked over 2000 people between my Facebook and Twitter accounts. The Facebook crowd, ironically, responded more enthusiastically, even though on Facebook I am mostly connected to people I know in real life who may or may not be that into movies. On Twitter, where most of my active connections actually are movie bloggers and classic film fans, I got a lot fewer replies. Too much noise in the system there, I guess, compared to the 400+ people on Facebook.

Have you seen every movie that made the top ten list? What is your favorite funny movie? Let me know in the comments! If you're interested in learning more about David Misch's book, you can read my review of it here.

Monday, April 21, 2014

FUNNY: THE BOOK by David Misch

David Misch, a TV and movie writer whose work includes Mork & Mindy, Duckman, and The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984), is a big fan of classic movie comedies, which shows in his book-length contemplation of comedy, Funny: The Book (2012). Although not targeted specifically at classic movie fans, Funny: The Book certainly has plenty to keep those readers entertained, but it also ranges far and wide across human history to ponder the nature of humor, even taking in biology, religion, Lenny Bruce, and existentialist philosophy. The result is a book that is thought-provoking, educational, and, yes, funny, and it really ought to appeal to anyone who wants to take comedy a little more seriously.

Misch devotes whole sections of his book to personal favorites like The Marx Brothers and Buster Keaton, but classic movie references and discussions pop up in every chapter (the caption beneath one photo of Edward G. Robinson in Little Caesar made me laugh, but of course it's only funny if you recognize Robinson and the role he's playing). Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Mae West, and Laurel & Hardy all make appearances, as well. Even chapters that are really about more recent comedians and other genres reveal Misch's interest in and knowledge of classic film.

Cinephiles with a looser definition of "classic" will particularly enjoy chapters about Steve Martin, Woody Allen, and Richard Pryor, while those who also keep up with current media will appreciate the discussion of The Office. The academically inclined will approve of Misch's efforts to cover ancient history, mythology, the Jungian concept of the Trickster, and even the physiological aspects of humor. Misch manages to incorporate a lot of intellectual material into the book in a way that makes it painless and even entertaining to absorb.

If you happen to be familiar with Charlene Fix's 2013 book, Harpo Marx as Trickster, you will definitely find an interesting parallel in Misch's work, since both books cover the Trickster archetype and the Marx Brothers as embodiments of it, although each author explores the idea in a unique way. Those who enjoy Misch's chapter on Buster Keaton should also check out Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts: 1920-1923 by James L. Neibaur and Terri Niemi, which goes into more detail about Keaton's particular style of comedy. Edward McPherson's 2007 biography, Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat, would also make a very good follow-up selection.

Personally, I really enjoyed Funny: The Book, and it prompted me to think about the classic movie comedies I love and why they make me laugh. I was particularly inspired to ask other people what movies they thought were funny and why, and there might well be an upcoming blog post on that topic.

To sum it all up - If you read Funny: The Book, be prepared to laugh out loud and think deeply at the same time.

Note: The publisher provided me with a free review copy of this book. No promise of a positive review was made or expected in exchange for this courtesy.

Misch devotes whole sections of his book to personal favorites like The Marx Brothers and Buster Keaton, but classic movie references and discussions pop up in every chapter (the caption beneath one photo of Edward G. Robinson in Little Caesar made me laugh, but of course it's only funny if you recognize Robinson and the role he's playing). Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Mae West, and Laurel & Hardy all make appearances, as well. Even chapters that are really about more recent comedians and other genres reveal Misch's interest in and knowledge of classic film.

Cinephiles with a looser definition of "classic" will particularly enjoy chapters about Steve Martin, Woody Allen, and Richard Pryor, while those who also keep up with current media will appreciate the discussion of The Office. The academically inclined will approve of Misch's efforts to cover ancient history, mythology, the Jungian concept of the Trickster, and even the physiological aspects of humor. Misch manages to incorporate a lot of intellectual material into the book in a way that makes it painless and even entertaining to absorb.

If you happen to be familiar with Charlene Fix's 2013 book, Harpo Marx as Trickster, you will definitely find an interesting parallel in Misch's work, since both books cover the Trickster archetype and the Marx Brothers as embodiments of it, although each author explores the idea in a unique way. Those who enjoy Misch's chapter on Buster Keaton should also check out Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts: 1920-1923 by James L. Neibaur and Terri Niemi, which goes into more detail about Keaton's particular style of comedy. Edward McPherson's 2007 biography, Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat, would also make a very good follow-up selection.

Personally, I really enjoyed Funny: The Book, and it prompted me to think about the classic movie comedies I love and why they make me laugh. I was particularly inspired to ask other people what movies they thought were funny and why, and there might well be an upcoming blog post on that topic.

To sum it all up - If you read Funny: The Book, be prepared to laugh out loud and think deeply at the same time.

Note: The publisher provided me with a free review copy of this book. No promise of a positive review was made or expected in exchange for this courtesy.

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Great Villain Blogathon: Laird Cregar in HANGOVER SQUARE (1945)

This post is part of the Great Villain Blogathon hosted by Ruth of Silver Screenings, Karen of Shadows & Satin, and Kristina of Speakeasy — see all the movie baddies at any of these three blogs.

The Fox studio heads were certain that Laird Cregar was born to play villains, never mind that Cregar himself dreamed of being a romantic lead. In Hangover Square (1945), the final film of his tragically brief career, Cregar got to do both at once, creating for viewers a sympathetic, romantic figure who also happens to be a homicidal maniac. The price for his effort would prove high, indeed; Cregar died of a massive heart attack, brought on by his radical weight loss program, before Hangover Square made its way to the screen. The movie reveals the extent of the public's loss, for Cregar gives a powerhouse performance as a brilliant young composer driven to madness and murder by a heartless chanteuse (Linda Darnell) and the jarring shock of any discordant sound.

John Brahm, who directed Hangover Square, had previously directed Cregar in The Lodger (1944), in which Cregar plays Jack the Ripper as a pathetic monster driven to kill by his grief over the death of his brother. Twentieth Century Fox reunited Brahm and Cregar for a follow-up that was meant to play all of the same notes that had made the earlier movie a success, including a Victorian setting and George Sanders in a supporting role, but Cregar had other ideas. Dropping a huge amount of weight in a very short period of time, Cregar reshaped himself into more conventional leading man material and thereby added a whole new layer to his character by making the audience believe that women might actually find him attractive.

If you know Cregar's story, it's hard to watch Hangover Square without pondering these offscreen elements. We're watching an actor who is, quite literally, giving his life for his art. Here is a man who doesn't want to be known as a monster but seems trapped in that fate, anyway, which eerily parallels the story of the fictional character Cregar is playing. When the doomed protagonist goes up in smoke at the movie's end, we're left thinking about Cregar's own sudden departure from this world. He was only 31 years old, with just five years of films behind him.

Still, it's important to look closely at that performance on its own merits in order to appreciate and lament Cregar as much as he deserves. As Cregar plays him, George Harvey Bone is a shy, gifted composer who can't help turning into an insane killer every time a harsh sound assaults his ears. He's not bad; he's just really sensitive. In many ways, Bone resembles Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man (1941); an outside stimulus over which the protagonist has no control dictates his actions and ultimately his fate. As the gypsies say, "Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright." Cregar, however, has to define the two sides of his character without any help from monster makeup; he does it all through his performance and the way he looks, like a wide-eyed sleepwalker lost in a maze of horrors.

As the doomed composer, Cregar taps into the same combination of the monstrous and pitiable that makes other movie monsters sublime: Lon Chaney as The Phantom of the Opera, Boris Karloff as both Frankenstein's monster and Imhotep, Claude Rains as The Invisible Man, and Chaney, Jr. as The Wolf Man. They are all beings who long for love, particularly from beautiful young women, but they can neither control nor deny their own monstrosity. Death and ruin follow them as surely as night follows day. Cregar accomplishes as much in his performance as any of these iconic actors, but he does it by flipping a switch within himself, not by transforming into a literal monster with fangs and claws or other outward markers of the bestial id let loose. Perhaps that makes his monster more frightening, because we know it could happen to any of us without the occurrence of the supernatural. George Harvey Bone drinks no potions; nothing extraordinary happens to explain his murderous urges. He's walking along, minding his own business, and suddenly the world lurches forward with a crashing sound and something terrible has happened. It's no wonder he chooses the certainty of death in the movie's finale. He can only reclaim his humanity by destroying his monstrosity, and to do that he must destroy himself.

Laird Cregar is not a household name today; for the most part, only serious classic movie fans remember him. He played villains so well - in Blood and Sand (1941), This Gun for Hire (1942), and The Lodger (1944) as well as in Hangover Square - that it's a shame to think that he died trying to be something else. Still, with the few films that he made, Cregar proved his genius for being more than a monster. He was truly a great actor, too.

Read my essay, "Heavy: The Life and Films of Laird Cregar," to learn more about the actor and his work.

The Fox studio heads were certain that Laird Cregar was born to play villains, never mind that Cregar himself dreamed of being a romantic lead. In Hangover Square (1945), the final film of his tragically brief career, Cregar got to do both at once, creating for viewers a sympathetic, romantic figure who also happens to be a homicidal maniac. The price for his effort would prove high, indeed; Cregar died of a massive heart attack, brought on by his radical weight loss program, before Hangover Square made its way to the screen. The movie reveals the extent of the public's loss, for Cregar gives a powerhouse performance as a brilliant young composer driven to madness and murder by a heartless chanteuse (Linda Darnell) and the jarring shock of any discordant sound.

John Brahm, who directed Hangover Square, had previously directed Cregar in The Lodger (1944), in which Cregar plays Jack the Ripper as a pathetic monster driven to kill by his grief over the death of his brother. Twentieth Century Fox reunited Brahm and Cregar for a follow-up that was meant to play all of the same notes that had made the earlier movie a success, including a Victorian setting and George Sanders in a supporting role, but Cregar had other ideas. Dropping a huge amount of weight in a very short period of time, Cregar reshaped himself into more conventional leading man material and thereby added a whole new layer to his character by making the audience believe that women might actually find him attractive.

If you know Cregar's story, it's hard to watch Hangover Square without pondering these offscreen elements. We're watching an actor who is, quite literally, giving his life for his art. Here is a man who doesn't want to be known as a monster but seems trapped in that fate, anyway, which eerily parallels the story of the fictional character Cregar is playing. When the doomed protagonist goes up in smoke at the movie's end, we're left thinking about Cregar's own sudden departure from this world. He was only 31 years old, with just five years of films behind him.

Still, it's important to look closely at that performance on its own merits in order to appreciate and lament Cregar as much as he deserves. As Cregar plays him, George Harvey Bone is a shy, gifted composer who can't help turning into an insane killer every time a harsh sound assaults his ears. He's not bad; he's just really sensitive. In many ways, Bone resembles Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man (1941); an outside stimulus over which the protagonist has no control dictates his actions and ultimately his fate. As the gypsies say, "Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright." Cregar, however, has to define the two sides of his character without any help from monster makeup; he does it all through his performance and the way he looks, like a wide-eyed sleepwalker lost in a maze of horrors.

As the doomed composer, Cregar taps into the same combination of the monstrous and pitiable that makes other movie monsters sublime: Lon Chaney as The Phantom of the Opera, Boris Karloff as both Frankenstein's monster and Imhotep, Claude Rains as The Invisible Man, and Chaney, Jr. as The Wolf Man. They are all beings who long for love, particularly from beautiful young women, but they can neither control nor deny their own monstrosity. Death and ruin follow them as surely as night follows day. Cregar accomplishes as much in his performance as any of these iconic actors, but he does it by flipping a switch within himself, not by transforming into a literal monster with fangs and claws or other outward markers of the bestial id let loose. Perhaps that makes his monster more frightening, because we know it could happen to any of us without the occurrence of the supernatural. George Harvey Bone drinks no potions; nothing extraordinary happens to explain his murderous urges. He's walking along, minding his own business, and suddenly the world lurches forward with a crashing sound and something terrible has happened. It's no wonder he chooses the certainty of death in the movie's finale. He can only reclaim his humanity by destroying his monstrosity, and to do that he must destroy himself.

Laird Cregar is not a household name today; for the most part, only serious classic movie fans remember him. He played villains so well - in Blood and Sand (1941), This Gun for Hire (1942), and The Lodger (1944) as well as in Hangover Square - that it's a shame to think that he died trying to be something else. Still, with the few films that he made, Cregar proved his genius for being more than a monster. He was truly a great actor, too.

Read my essay, "Heavy: The Life and Films of Laird Cregar," to learn more about the actor and his work.

Friday, April 18, 2014

Classic Films in Focus: EASTER PARADE (1948)

This colorful MGM musical includes all the bonnets and fancy new outfits one might expect from a movie called Easter Parade, but the chief attraction of the 1948 film is the pairing of two of the genre’s biggest stars, Fred Astaire and Judy Garland, as a song and dance team trying to make it big in the Ziegfeld era. The Irving Berlin tunes and supporting performances from Ann Miller and Peter Lawford also make Easter Parade a memorable springtime confection, although like most sweets - and Fred Astaire musicals - it’s a little light on substance. If, however, you’re looking for an antidote to the heavy religious epics that often dominate the Easter movie lineup, then Easter Parade is a perfect choice, a light, bright romantic romp bursting with humor and style.

Astaire pays famous hoofer Don Hewes, whose Easter celebration is cut short when his partner, Nadine (Ann Miller), announces that she’s leaving for a solo career. Determined to win Nadine back by showing her that he doesn’t need her, Don sets out to make a successful partner of the next girl he meets, who happens to be novice dancer Hannah Brown (Judy Garland). Don’s friend, Johnny (Peter Lawford), promptly falls for Hannah, but Hannah pines for Don, while Don still harbors feelings for Nadine. As one Easter gives way to the next, the performers see their careers take off, but their romantic lives remain stalled, especially after a jealous Nadine makes a public play for Don’s attention.

Two very different partners give Fred Astaire a chance to change pace in the film’s dance numbers. Ann Miller is the more powerful and assertive dancer of the two leading ladies, but Judy Garland excels at light comedy bits like “We’re a Couple of Swells” and the Vaudeville montage sequence. As singers, Miller brings the sex appeal with “Shakin’ the Blues Away,” while Garland pulls out the pathos in her rendition of “Better Luck Next Time.” Astaire’s solo performances are also a lot of fun, especially the “Drum Crazy” piece in the toy store, where Don distracts a rival customer from a stuffed Easter bunny by dancing with a whole collection of brightly painted drums. Of course, the earworm of the lot is “Easter Parade,” which you might well end up crooning for days once you hear Garland sing it.

The plot serves mostly to string the musical segments together, which helps to explain why we get so little resolution about what happens with Nadine and Johnny at the end. Astaire’s character seems headed into Pygmalion territory early on, but he realizes his mistake and stops trying to make Hannah into another Nadine, so the only remaining tension depends on the characters’ misplaced affections. Ann Miller’s stage diva is the closest thing the story has to an antagonist, but it’s really very hard to dislike her when her performances are so delightful. Nadine is shallow, uses dogs as fashion accessories, and hopes that Don and Hannah will be a flop, but Hannah imagines Nadine as much more of a threat than she really is. The handsome, young Peter Lawford ought to give the much older Astaire more competition for the heroine’s attention, but as likable as he is Lawford lacks the charisma that makes a short, balding, middle-aged dancer one of Hollywood’s greatest stars.

Be sure to appreciate the screen debut of Jules Munshin as the hilarious headwaiter; he would go on to star with Gene Kelly in Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1949) and On the Town (1949). Director Charles Walters worked with Astaire again in The Barkleys of Broadway (1949) and also directed Garland in Summer Stock (1950). Although Easter Parade is the only true pairing of Fred Astaire and Judy Garland, you’ll find both of them in separate numbers in Ziegfeld Follies (1945). See more of Peter Lawford in Good News (1947), Little Women (1949), and Royal Wedding (1951), which also stars Fred Astaire.

Astaire pays famous hoofer Don Hewes, whose Easter celebration is cut short when his partner, Nadine (Ann Miller), announces that she’s leaving for a solo career. Determined to win Nadine back by showing her that he doesn’t need her, Don sets out to make a successful partner of the next girl he meets, who happens to be novice dancer Hannah Brown (Judy Garland). Don’s friend, Johnny (Peter Lawford), promptly falls for Hannah, but Hannah pines for Don, while Don still harbors feelings for Nadine. As one Easter gives way to the next, the performers see their careers take off, but their romantic lives remain stalled, especially after a jealous Nadine makes a public play for Don’s attention.

Two very different partners give Fred Astaire a chance to change pace in the film’s dance numbers. Ann Miller is the more powerful and assertive dancer of the two leading ladies, but Judy Garland excels at light comedy bits like “We’re a Couple of Swells” and the Vaudeville montage sequence. As singers, Miller brings the sex appeal with “Shakin’ the Blues Away,” while Garland pulls out the pathos in her rendition of “Better Luck Next Time.” Astaire’s solo performances are also a lot of fun, especially the “Drum Crazy” piece in the toy store, where Don distracts a rival customer from a stuffed Easter bunny by dancing with a whole collection of brightly painted drums. Of course, the earworm of the lot is “Easter Parade,” which you might well end up crooning for days once you hear Garland sing it.

The plot serves mostly to string the musical segments together, which helps to explain why we get so little resolution about what happens with Nadine and Johnny at the end. Astaire’s character seems headed into Pygmalion territory early on, but he realizes his mistake and stops trying to make Hannah into another Nadine, so the only remaining tension depends on the characters’ misplaced affections. Ann Miller’s stage diva is the closest thing the story has to an antagonist, but it’s really very hard to dislike her when her performances are so delightful. Nadine is shallow, uses dogs as fashion accessories, and hopes that Don and Hannah will be a flop, but Hannah imagines Nadine as much more of a threat than she really is. The handsome, young Peter Lawford ought to give the much older Astaire more competition for the heroine’s attention, but as likable as he is Lawford lacks the charisma that makes a short, balding, middle-aged dancer one of Hollywood’s greatest stars.

Be sure to appreciate the screen debut of Jules Munshin as the hilarious headwaiter; he would go on to star with Gene Kelly in Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1949) and On the Town (1949). Director Charles Walters worked with Astaire again in The Barkleys of Broadway (1949) and also directed Garland in Summer Stock (1950). Although Easter Parade is the only true pairing of Fred Astaire and Judy Garland, you’ll find both of them in separate numbers in Ziegfeld Follies (1945). See more of Peter Lawford in Good News (1947), Little Women (1949), and Royal Wedding (1951), which also stars Fred Astaire.

Monday, April 14, 2014

Book Review: COMPLICATED WOMEN by Mick LaSalle

First published in 2001, Mick LaSalle's Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood is primarily a feminist consideration of Pre-Code actresses and the roles they were able to play before Joseph Breen threw a big, wet blanket on the Tinseltown party in 1934. Although it is probably not an ideal introduction to Pre-Code pictures for the absolute novice, Complicated Women is a very good resource for those who already know something about the era and its stars, and it's written in a casual, personal voice that will appeal to classic movie fans who aren't necessarily academic in their approach to pictures.

LaSalle, who reviews movies for the San Francisco Chronicle, focuses on the actresses who helped to define the distinctive themes and styles of the Pre-Code era. Starting with Norma Shearer and Greta Garbo, he works his way through discussions of Jean Harlow, Barbara Stanwyck, Kay Francis, Joan Crawford, Ann Harding, Joan Blondell, Ann Dvorak, Miriam Hopkins, and other leading ladies who rose to stardom during the early days of the talkies. LaSalle contrasts the kinds of pictures these women were making before 1934 with the melodramas that came into favor after the strict enforcement of the Hays Code, and he argues that Hollywood - and perhaps society as a whole - were forced to take a big step backwards in terms of women's liberties and sexual freedom because of the rabidly conservative forces that lined up behind Joseph Breen. In LaSalle's view, the Hays Code was primarily and vindictively concerned with screen images of women enjoying active sex lives, pursuing careers, and being perceived as morally complex individuals; the Code attempted to shut down these visions of gender equality and force women to see themselves in the old 19th-century roles as domestic angels or worldly temptresses, with the temptresses inevitably being punished for their sins.

The book reveals LaSalle's particular interest in Shearer and Garbo, to whom he devotes the lion's share of his attention. In contrast, he clearly has no love for Joan Crawford, whom he often describes in pejorative terms. While his discussions of Harlow, Stanwyck, and Blondell are intriguing, most readers will probably finish the book wishing there had been more pages dedicated to them. There's a reason Norma Shearer graces the cover of Complicated Women, and Shearer fans will be delighted to find LaSalle championing her cause most emphatically. LaSalle's treatment of the movies made in the later 1930s and 1940s might upset fans of that period, especially those who love the women's weepies, or melodramas, that made huge stars of Crawford and Bette Davis. LaSalle finds these pictures stifling in their reactionary images of women who must give up sexual freedom, economic independence, and even personal integrity in order to please the flawed men who expect so much from them. He observes that 1940s film noir escapes from the Code's strictures in its depictions of the femme fatale, who often conforms to the letter of the Code by getting killed for her iniquities but also impresses viewers with her strength and refusal to submit to conventional morality. Toward the end of the book, LaSalle speculates about more modern actresses as the heirs to Shearer and Garbo's legacies, but classic movie fans might find these segments the least compelling of the whole work, since they deal in actresses who might not even be familiar to those who haven't seen a lot of their films.

Reading the book in 2014, it's hard not to wonder what LaSalle thinks has changed since Complicated Women was first published. Pre-Code movies have become much easier to watch with the advent of streaming and specialized services and television channels. Has Shearer's reputation risen with the success of Turner Classic Movies and the arrival of Warner Archive and Warner Archive Instant? Have the movies finally caught up with Pre-Code visions of women's sexual and professional lives? While LaSalle did publish a follow-up, Dangerous Men: Pre-Code Hollywood and the Birth of the Modern Man, in 2002, he hasn't produced another book since then. Maybe it's time for him to provide readers with a new consideration of Pre-Codes that turns more of its attention to the other actresses who enjoyed their greatest success during that brief, wild fling before Breen and his cronies shut the party down.

Complicated Women is currently available in paperback on Amazon for just over $12. It would make a great Mother's Day gift for Norma Shearer devotees or fans of Pre-Code film.

LaSalle, who reviews movies for the San Francisco Chronicle, focuses on the actresses who helped to define the distinctive themes and styles of the Pre-Code era. Starting with Norma Shearer and Greta Garbo, he works his way through discussions of Jean Harlow, Barbara Stanwyck, Kay Francis, Joan Crawford, Ann Harding, Joan Blondell, Ann Dvorak, Miriam Hopkins, and other leading ladies who rose to stardom during the early days of the talkies. LaSalle contrasts the kinds of pictures these women were making before 1934 with the melodramas that came into favor after the strict enforcement of the Hays Code, and he argues that Hollywood - and perhaps society as a whole - were forced to take a big step backwards in terms of women's liberties and sexual freedom because of the rabidly conservative forces that lined up behind Joseph Breen. In LaSalle's view, the Hays Code was primarily and vindictively concerned with screen images of women enjoying active sex lives, pursuing careers, and being perceived as morally complex individuals; the Code attempted to shut down these visions of gender equality and force women to see themselves in the old 19th-century roles as domestic angels or worldly temptresses, with the temptresses inevitably being punished for their sins.

The book reveals LaSalle's particular interest in Shearer and Garbo, to whom he devotes the lion's share of his attention. In contrast, he clearly has no love for Joan Crawford, whom he often describes in pejorative terms. While his discussions of Harlow, Stanwyck, and Blondell are intriguing, most readers will probably finish the book wishing there had been more pages dedicated to them. There's a reason Norma Shearer graces the cover of Complicated Women, and Shearer fans will be delighted to find LaSalle championing her cause most emphatically. LaSalle's treatment of the movies made in the later 1930s and 1940s might upset fans of that period, especially those who love the women's weepies, or melodramas, that made huge stars of Crawford and Bette Davis. LaSalle finds these pictures stifling in their reactionary images of women who must give up sexual freedom, economic independence, and even personal integrity in order to please the flawed men who expect so much from them. He observes that 1940s film noir escapes from the Code's strictures in its depictions of the femme fatale, who often conforms to the letter of the Code by getting killed for her iniquities but also impresses viewers with her strength and refusal to submit to conventional morality. Toward the end of the book, LaSalle speculates about more modern actresses as the heirs to Shearer and Garbo's legacies, but classic movie fans might find these segments the least compelling of the whole work, since they deal in actresses who might not even be familiar to those who haven't seen a lot of their films.

Reading the book in 2014, it's hard not to wonder what LaSalle thinks has changed since Complicated Women was first published. Pre-Code movies have become much easier to watch with the advent of streaming and specialized services and television channels. Has Shearer's reputation risen with the success of Turner Classic Movies and the arrival of Warner Archive and Warner Archive Instant? Have the movies finally caught up with Pre-Code visions of women's sexual and professional lives? While LaSalle did publish a follow-up, Dangerous Men: Pre-Code Hollywood and the Birth of the Modern Man, in 2002, he hasn't produced another book since then. Maybe it's time for him to provide readers with a new consideration of Pre-Codes that turns more of its attention to the other actresses who enjoyed their greatest success during that brief, wild fling before Breen and his cronies shut the party down.

Complicated Women is currently available in paperback on Amazon for just over $12. It would make a great Mother's Day gift for Norma Shearer devotees or fans of Pre-Code film.

Sunday, April 13, 2014

James Stewart Blogathon: DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1939)

This post is part of the James Stewart Blogathon hosted by the Classic Film & TV Cafe. You can view the complete blogathon schedule here.

If we come to Jimmy Stewart as a Western star looking back from the present, we peer through a history that makes his appearance in the genre seem obvious, perhaps even necessary. We see him in The Shootist (1976) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) with that greatest of Western icons, John Wayne, and he holds his own there as a believable resident of Wayne’s frontier world. Stewart seems as much a part of the genre’s history as his real life friend, Henry Fonda, with whom he starred in The Cheyenne Social Club (1970) and Firecreek (1968). All three Western stars would appear in How the West was Won (1962), which is basically a who’s who of the genre. Thus, from where we stand now, Stewart looks like a natural part of the Western landscape, but that wasn't the case at all in 1939, when Stewart starred in Destry Rides Again.

It was the first Western of the young actor's career, and at that point Stewart seemed an odd choice for the role. Tall and amiable, with an air of peculiarly American innocence, Stewart had primarily been seen in romances and comedies. Frank Capra had put him to good use in You Can't Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), but Destry was entirely new territory. It took Stewart out of the polite, civilized settings he had previously inhabited and dropped him into the rugged and rowdy frontier.

Stewart plays the film's title character, the son of a legendary lawman and the last hope of the honest citizens of Bottleneck, a wild, corrupted frontier town. Summoned by the town drunk (Charles Winninger), whom the crooks have made sheriff as a cruel joke, Destry at first seems like a terrible disappointment. He doesn't even carry a gun. As Destry says, however, first impressions are darn fool things, and even the local good time girl (Marlene Dietrich) is drawn to him, despite her understanding with the conniving crime boss (Brian Donlevy). When the crooks murder Destry's friend, he is compelled to take up his guns and rid the town of its oppressors for good.

Stewart makes Destry work precisely because he seems so unlikely as a gunslinger. Lanky, soft-spoken, and polite, Stewart's hero doesn't strike anyone as a threat, much less a gunfighter. Destry, of course, knows his own ability and lets the townspeople wallow in their assumptions. Stewart invests him with an easy nature that is only mistaken for weakness. In fact, it's born of self-assurance. When he finally takes out his guns, we see the other side of Destry's character, and this is where Stewart surprises us most. He is tough. He can be a dangerous man. There's a whole future unfolding for Stewart in this moment, one that will make him an icon not only for It's a Wonderful Life (1946) but also for Winchester '73 (1950), The Man from Laramie (1955), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. There's an unexpected edge to Stewart that later directors will seize upon: Anthony Mann will reveal Stewart's darkness as an underlying vein of hysteria in The Naked Spur (1953), and Alfred Hitchcock will make it the sublime theme of his masterpiece, Vertigo (1958). Despite the fact that Destry Rides Again is technically a comedy, it actually paves the way for Stewart to venture far beyond the territory he had covered in the Capra pictures or early work like Wife vs. Secretary (1936), Born to Dance (1936), or Vivacious Lady (1938).

Thus, as a Jimmy Stewart picture, Destry Rides Again is a watershed moment in the actor's career. Only by looking back at it from the perspective of 1939 can we really appreciate how important it would become in terms of Stewart's own legacy and the evolution of the Western as a whole. Destry opens the door for an actor who would go on to make some of the finest Westerns in Hollywood history, one who would become so associated with the genre that his final screen credit would be for his performance in a Western tale. By the time he loaned his voice to An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), Stewart was as much a part of the Western as any actor who ever rode a horse into a dusty frontier town. For that, we have Destry to thank.

If we come to Jimmy Stewart as a Western star looking back from the present, we peer through a history that makes his appearance in the genre seem obvious, perhaps even necessary. We see him in The Shootist (1976) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) with that greatest of Western icons, John Wayne, and he holds his own there as a believable resident of Wayne’s frontier world. Stewart seems as much a part of the genre’s history as his real life friend, Henry Fonda, with whom he starred in The Cheyenne Social Club (1970) and Firecreek (1968). All three Western stars would appear in How the West was Won (1962), which is basically a who’s who of the genre. Thus, from where we stand now, Stewart looks like a natural part of the Western landscape, but that wasn't the case at all in 1939, when Stewart starred in Destry Rides Again.

It was the first Western of the young actor's career, and at that point Stewart seemed an odd choice for the role. Tall and amiable, with an air of peculiarly American innocence, Stewart had primarily been seen in romances and comedies. Frank Capra had put him to good use in You Can't Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), but Destry was entirely new territory. It took Stewart out of the polite, civilized settings he had previously inhabited and dropped him into the rugged and rowdy frontier.

Stewart plays the film's title character, the son of a legendary lawman and the last hope of the honest citizens of Bottleneck, a wild, corrupted frontier town. Summoned by the town drunk (Charles Winninger), whom the crooks have made sheriff as a cruel joke, Destry at first seems like a terrible disappointment. He doesn't even carry a gun. As Destry says, however, first impressions are darn fool things, and even the local good time girl (Marlene Dietrich) is drawn to him, despite her understanding with the conniving crime boss (Brian Donlevy). When the crooks murder Destry's friend, he is compelled to take up his guns and rid the town of its oppressors for good.

Stewart makes Destry work precisely because he seems so unlikely as a gunslinger. Lanky, soft-spoken, and polite, Stewart's hero doesn't strike anyone as a threat, much less a gunfighter. Destry, of course, knows his own ability and lets the townspeople wallow in their assumptions. Stewart invests him with an easy nature that is only mistaken for weakness. In fact, it's born of self-assurance. When he finally takes out his guns, we see the other side of Destry's character, and this is where Stewart surprises us most. He is tough. He can be a dangerous man. There's a whole future unfolding for Stewart in this moment, one that will make him an icon not only for It's a Wonderful Life (1946) but also for Winchester '73 (1950), The Man from Laramie (1955), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. There's an unexpected edge to Stewart that later directors will seize upon: Anthony Mann will reveal Stewart's darkness as an underlying vein of hysteria in The Naked Spur (1953), and Alfred Hitchcock will make it the sublime theme of his masterpiece, Vertigo (1958). Despite the fact that Destry Rides Again is technically a comedy, it actually paves the way for Stewart to venture far beyond the territory he had covered in the Capra pictures or early work like Wife vs. Secretary (1936), Born to Dance (1936), or Vivacious Lady (1938).

Thus, as a Jimmy Stewart picture, Destry Rides Again is a watershed moment in the actor's career. Only by looking back at it from the perspective of 1939 can we really appreciate how important it would become in terms of Stewart's own legacy and the evolution of the Western as a whole. Destry opens the door for an actor who would go on to make some of the finest Westerns in Hollywood history, one who would become so associated with the genre that his final screen credit would be for his performance in a Western tale. By the time he loaned his voice to An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), Stewart was as much a part of the Western as any actor who ever rode a horse into a dusty frontier town. For that, we have Destry to thank.

Wednesday, April 9, 2014

Classic Films in Focus: HOLD YOUR MAN (1933)

Directed by Sam Wood, Hold Your Man (1933) is a Pre-Code women’s prison story with Jean Harlow as the primary jailbird and Clark Gable as the career con man who lands her there. Put those elements and stars together, and you’re certain to get one crackerjack of a picture, but despite its focus on rocky romance Hold Your Man also reveals a deeply benevolent interest in the lives of women behind bars. This is a story about tough guys and dames with surprisingly soft hearts, even those we little expect to see jumping ship to the side of the angels. With Anita Loos on the screenplay and an ensemble of fine supporting actresses populating the reformatory, Hold Your Man sympathizes with its women instead of exploiting them, which gives viewers all the more reason to love Jean Harlow as the impetuous, streetwise heroine.

Harlow plays Ruby, who gets a shock when fleeing con man Eddie (Clark Gable) bursts into her apartment in order to hide from the cops. Despite being surprised while taking a bath, Ruby covers for Eddie, and after a short while they reunite and become lovers, much to the disgruntlement of Eddie’s former squeeze, Gypsy (Dorothy Burgess). Eddie decides to con one of Ruby’s admirers by luring him into a compromising tryst, but Ruby gets nabbed by the police after Eddie accidentally kills the mark in a jealous scuffle. In the reformatory, Ruby contends with the angry Gypsy, realizes that she is pregnant with Eddie’s child, and wonders if her lover has abandoned her to her fate.

Gable and Harlow appeared in six pictures together, with Hold Your Man coming just after their steamy collaboration in Red Dust (1932). As Ruby and Eddie, they prove that their chemistry in the previous film was no fluke. Gable tosses Harlow lines, and she knocks them out of the park, but all the while they both have a look that says they really enjoy this sort of game. The second half of the movie offers them more serious scenes, especially when Eddie sneaks into the reformatory to see Ruby and then hatches a crazy plan to marry her on the spot. Love proves powerful enough to make both of them go straight, especially when Eddie realizes that Ruby is carrying his baby. Both actors are perfectly cast as these dynamic characters, since both can play crooks without making us like them any less. If Ruby is fleecing lovers like the gullible Al (Stuart Erwin), well, a girl has to make a living somehow, and since Al doesn’t hold it against her we can’t, either.

The supporting cast really shines in the reformatory scenes, where we find a world of characters who defy stereotypes in their emotional complexity. Dorothy Burgess fills Gypsy with jealous spite during her first encounters with Ruby but later reveals her own capacity for change and becomes an important ally. Blanche Friderici gives a subtle but effective performance as the reformatory matron, Mrs. Wagner, who sympathizes with her charges in their sorrows and their hopes. Most striking is the uncredited appearance of the fantastic Theresa Harris as Lily Mae, a preacher’s daughter whose own father sends her to the reformatory not because he rejects her, but because he loves her and wants her to become a better person. Even though she is African-American, everyone in the prison treats Lily Mae as an equal, but the racism of the period denied the actress the credit she thoroughly deserved for her work. Muriel Kirkland and Inez Courtney add to the reformatory atmosphere but don’t actually contribute more than Harris. George Reed, also uncredited, makes the most of a few brief scenes as Lily Mae’s father, who listens to a higher power when he agrees to hide out in the reformatory in order to marry the desperate couple.

Some viewers might complain that the ending of Hold Your Man is too sentimental, but for most its sincerity about love will add to its appeal. Pair it with Ladies They Talk About (1933) for another Pre-Code take on women in love and behind bars. For more of Harlow and Gable, see China Seas (1935), Wife vs. Secretary (1936), and Saratoga (1937). Be sure to appreciate Theresa Harris in Baby Face (1933), Jezebel (1938), and I Walked with a Zombie (1943). Sam Wood earned Oscar nominations for Best Director for Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), Kitty Foyle (1940), and Kings Row (1942), but he also directed the Marx Brothers in A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937). Anita Loos, who wrote the screenplays for many memorable films of the 1930s, also wrote the novel from which Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was adapted in both 1928 and 1953.

Hold Your Man is currently streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Harlow plays Ruby, who gets a shock when fleeing con man Eddie (Clark Gable) bursts into her apartment in order to hide from the cops. Despite being surprised while taking a bath, Ruby covers for Eddie, and after a short while they reunite and become lovers, much to the disgruntlement of Eddie’s former squeeze, Gypsy (Dorothy Burgess). Eddie decides to con one of Ruby’s admirers by luring him into a compromising tryst, but Ruby gets nabbed by the police after Eddie accidentally kills the mark in a jealous scuffle. In the reformatory, Ruby contends with the angry Gypsy, realizes that she is pregnant with Eddie’s child, and wonders if her lover has abandoned her to her fate.

Gable and Harlow appeared in six pictures together, with Hold Your Man coming just after their steamy collaboration in Red Dust (1932). As Ruby and Eddie, they prove that their chemistry in the previous film was no fluke. Gable tosses Harlow lines, and she knocks them out of the park, but all the while they both have a look that says they really enjoy this sort of game. The second half of the movie offers them more serious scenes, especially when Eddie sneaks into the reformatory to see Ruby and then hatches a crazy plan to marry her on the spot. Love proves powerful enough to make both of them go straight, especially when Eddie realizes that Ruby is carrying his baby. Both actors are perfectly cast as these dynamic characters, since both can play crooks without making us like them any less. If Ruby is fleecing lovers like the gullible Al (Stuart Erwin), well, a girl has to make a living somehow, and since Al doesn’t hold it against her we can’t, either.

The supporting cast really shines in the reformatory scenes, where we find a world of characters who defy stereotypes in their emotional complexity. Dorothy Burgess fills Gypsy with jealous spite during her first encounters with Ruby but later reveals her own capacity for change and becomes an important ally. Blanche Friderici gives a subtle but effective performance as the reformatory matron, Mrs. Wagner, who sympathizes with her charges in their sorrows and their hopes. Most striking is the uncredited appearance of the fantastic Theresa Harris as Lily Mae, a preacher’s daughter whose own father sends her to the reformatory not because he rejects her, but because he loves her and wants her to become a better person. Even though she is African-American, everyone in the prison treats Lily Mae as an equal, but the racism of the period denied the actress the credit she thoroughly deserved for her work. Muriel Kirkland and Inez Courtney add to the reformatory atmosphere but don’t actually contribute more than Harris. George Reed, also uncredited, makes the most of a few brief scenes as Lily Mae’s father, who listens to a higher power when he agrees to hide out in the reformatory in order to marry the desperate couple.

Some viewers might complain that the ending of Hold Your Man is too sentimental, but for most its sincerity about love will add to its appeal. Pair it with Ladies They Talk About (1933) for another Pre-Code take on women in love and behind bars. For more of Harlow and Gable, see China Seas (1935), Wife vs. Secretary (1936), and Saratoga (1937). Be sure to appreciate Theresa Harris in Baby Face (1933), Jezebel (1938), and I Walked with a Zombie (1943). Sam Wood earned Oscar nominations for Best Director for Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), Kitty Foyle (1940), and Kings Row (1942), but he also directed the Marx Brothers in A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937). Anita Loos, who wrote the screenplays for many memorable films of the 1930s, also wrote the novel from which Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was adapted in both 1928 and 1953.

Hold Your Man is currently streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

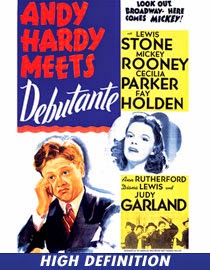

Classic Films in Focus: ANDY HARDY MEETS DEBUTANTE (1940)

This installment of the popular Andy Hardy series takes the Hardy family out of idyllic Carvel and sends them off to New York City, where teenage Andy promptly gets himself into all kinds of trouble. Despite the change of venue, it’s a typical Andy Hardy story, with youthful mistakes, romantic entanglements, and Mickey Rooney’s boundless zeal. You don’t have to have seen all of the previous Hardy pictures to drop into the action, although it does help if you have seen Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), the earlier movie that introduces Judy Garland’s Betsy Booth character. Garland’s return to the world of the Hardy family makes Andy Hardy Meets Debutante a particularly appealing picture for fans of her collaborations with the energetic Rooney. For newcomers, the distinctive mix of adolescent romance, humor, and wide-eyed American idealism sums up the essence of the Hardy films’ enduring appeal.

At home in Carvel, Andy is nursing a crush on New York society girl, Daphne Fowler (Diana Lewis), and he foolishly brags about knowing her when his friends discover his passion. Andy is forced to prove his claims when Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) takes the whole family to New York as part of his mission to protect the Carvel Orphanage from big city lawyers who want to defund it. Andy’s friend, Betsy (Judy Garland), tries to help him, but Andy suffers a series of shocks to his ego as he attempts to meet Daphne, and even Judge Hardy becomes concerned about the implications of Andy’s behavior.

Part of Andy Hardy’s appeal is his penchant for getting into scrapes; neither an angel nor a complete reprobate, he’s a twentieth-century Tom Sawyer with a waggish sense of fun and a lively eye for the ladies. Wherever Andy goes, girl trouble follows, and in this outing he has Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford), Betsy, and Daphne to juggle. Andy thinks he’s too sophisticated for Polly, and he treats Betsy like a kid, but he soon finds out that the wealthy Daphne is out of his league. “There are millions of nice people in the world,” Daphne’s mother tells him, “and Daphne can’t be friends with all of them.” The irony of his comeuppance never seems to dawn on Andy, but the audience sees quite clearly that he reaps as he has sown. His taste in girls needs adjusting, anyway, if he can favor Daphne over her more available competition. Polly, the hometown favorite, wins our approval thanks to Ann Rutherford’s flashing eyes and bold manner, while Judy Garland makes Betsy so sweet and sadly lovestruck that we root for her even though we know that Polly has already staked her claim. Garland’s performance of “Alone,” which starts as a gag and ends with tears, is an emotional highlight of the picture that showcases the young star’s tremendous talent.

Comedy tempered with sentiment is the Andy Hardy formula, and the threat to the orphanage provides a counterweight to Andy’s romantic hijinks. Judge Hardy proves his faith in the system, lectures Andy on American ideals, and wins over a courtroom with the assistance of an adorable orphan, all of which will strike modern viewers as terribly naive. Still, with the Depression in the rearview mirror and the war directly ahead, Americans in 1940 must have wanted very much to believe in the benevolent paternal authority that Judge Hardy embodies. Andy’s relationship with his father gets a great deal of play, while his mother, aunt, and sister hardly make appearances at all. The serious part of Andy Hardy Meets Debutante has nothing to do with women but concerns itself with Andy’s emerging identity as a man with a particular place in the world.

The Andy Hardy series continued until 1958, when Mickey Rooney made his final bow as the character in Andy Hardy Comes Home. George B. Seitz directed most of the Andy Hardy pictures, beginning with A Family Affair (1937), You’re Only Young Once (1937), and Judge Hardy’s Children (1938). For more of Mickey Rooney’s youthful roles, see A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), Captains Courageous (1937), and Boys Town (1938). Diana Lewis, who was married to William Powell for more than forty years, retired from acting in the early 1940s after roles in Bitter Sweet (1940), Go West (1940), and Johnny Eager (1941). If you enjoy the collaborative work of Rooney and Garland, be sure to see their musicals together, particularly Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), and Babes on Broadway (1941).

Andy Hardy Meets Debutante is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

At home in Carvel, Andy is nursing a crush on New York society girl, Daphne Fowler (Diana Lewis), and he foolishly brags about knowing her when his friends discover his passion. Andy is forced to prove his claims when Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) takes the whole family to New York as part of his mission to protect the Carvel Orphanage from big city lawyers who want to defund it. Andy’s friend, Betsy (Judy Garland), tries to help him, but Andy suffers a series of shocks to his ego as he attempts to meet Daphne, and even Judge Hardy becomes concerned about the implications of Andy’s behavior.

Part of Andy Hardy’s appeal is his penchant for getting into scrapes; neither an angel nor a complete reprobate, he’s a twentieth-century Tom Sawyer with a waggish sense of fun and a lively eye for the ladies. Wherever Andy goes, girl trouble follows, and in this outing he has Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford), Betsy, and Daphne to juggle. Andy thinks he’s too sophisticated for Polly, and he treats Betsy like a kid, but he soon finds out that the wealthy Daphne is out of his league. “There are millions of nice people in the world,” Daphne’s mother tells him, “and Daphne can’t be friends with all of them.” The irony of his comeuppance never seems to dawn on Andy, but the audience sees quite clearly that he reaps as he has sown. His taste in girls needs adjusting, anyway, if he can favor Daphne over her more available competition. Polly, the hometown favorite, wins our approval thanks to Ann Rutherford’s flashing eyes and bold manner, while Judy Garland makes Betsy so sweet and sadly lovestruck that we root for her even though we know that Polly has already staked her claim. Garland’s performance of “Alone,” which starts as a gag and ends with tears, is an emotional highlight of the picture that showcases the young star’s tremendous talent.

Comedy tempered with sentiment is the Andy Hardy formula, and the threat to the orphanage provides a counterweight to Andy’s romantic hijinks. Judge Hardy proves his faith in the system, lectures Andy on American ideals, and wins over a courtroom with the assistance of an adorable orphan, all of which will strike modern viewers as terribly naive. Still, with the Depression in the rearview mirror and the war directly ahead, Americans in 1940 must have wanted very much to believe in the benevolent paternal authority that Judge Hardy embodies. Andy’s relationship with his father gets a great deal of play, while his mother, aunt, and sister hardly make appearances at all. The serious part of Andy Hardy Meets Debutante has nothing to do with women but concerns itself with Andy’s emerging identity as a man with a particular place in the world.

The Andy Hardy series continued until 1958, when Mickey Rooney made his final bow as the character in Andy Hardy Comes Home. George B. Seitz directed most of the Andy Hardy pictures, beginning with A Family Affair (1937), You’re Only Young Once (1937), and Judge Hardy’s Children (1938). For more of Mickey Rooney’s youthful roles, see A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), Captains Courageous (1937), and Boys Town (1938). Diana Lewis, who was married to William Powell for more than forty years, retired from acting in the early 1940s after roles in Bitter Sweet (1940), Go West (1940), and Johnny Eager (1941). If you enjoy the collaborative work of Rooney and Garland, be sure to see their musicals together, particularly Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), and Babes on Broadway (1941).

Andy Hardy Meets Debutante is currently available for streaming on Warner Archive Instant.

Monday, April 7, 2014

Classic Films in Focus: CAT BALLOU (1965)

Director Elliot Silverstein’s 1965 Western comedy turned out to be an important moment in movie history, and not only because Cat Ballou became a box office hit and made Jane Fonda a star. It would provide Lee Marvin with the only Oscar of his exceptional career, and it would be the final screen appearance of the legendary Nat King Cole, who died before the movie was released. Cat Ballou also paved the way for later pictures like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Blazing Saddles (1974), and even The Villain (1979) and Rustler’s Rhapsody (1985), all of which kept the Western alive by subverting its familiar tropes. Its legacy, however, is not the picture’s only attraction; Cat Ballou is first and foremost a rollicking good time, with lively performances from its stars and a loving, if irreverent, attitude toward the genre it parodies.

Jane Fonda plays the title character, who returns home after finishing her education only to find her father, Frankie Ballou (John Marley), under pressure to sell out to developers. After Frankie is murdered by the notorious gunman Tim Strawn (Lee Marvin), Cat and her band of misfits turn to crime to avenge his death. Drunken gunfighter Kid Shelleen (also Lee Marvin) dries out for a final showdown with Strawn, while Clay (Michael Callan), Jed (Dwayne Hickman), and Jackson (Tom Nardini) agree to rob trains to prove their devotion to the determined Cat.