As wild as its plot and characters are, Doctor X (1932) is quite a thrill for fans of classic horror and the old dark house genre, especially those who can’t resist a mad scientist type. Directed by Michael Curtiz in the earlier years of his Hollywood career, the film makes use of both laughs and chills as it sends its cast careening through spooky rooms and strange laboratories, all rendered even more surreal by the use of an early form of Technicolor. The marvelous Lionel Atwill, a stalwart of classic horror, heads up a cast of creepy, colorful characters, each one stranger and more sinister than the last, while Fay Wray provides the sex appeal and Lee Tracy supplies the wise-cracking comic relief.

The story begins when a full moon inspires a series of gruesome murders, and the evidence points to one of the scientists in the employ of Dr. Xavier (Lionel Atwill). The doctor conducts his own investigation by experimenting on the scientists at a remote and ominous mansion, but his plans are intruded upon by persistent reporter Lee Taylor (Lee Tracy). Soon more corpses are piling up, and the the killer might not be discovered in time to save Dr. Xavier’s beautiful daughter, Joanne (Fay Wray), from a similar fate.

The plot revels in macabre elements, including the killer’s cannibalistic urges and strong hints about one scientist’s sadistic tendencies, and there are moments of pure horror scattered throughout the film. Lee Tracy’s snarky reporter, however, dispels most of the dread with his doggedly pragmatic pursuit of his story. In one scene he even disguises himself as a corpse in the morgue, and later he manages to get trapped in a closet full of skeletons, but his reactions to these situations are meant to provoke laughter instead of fear. More comic relief is provided by Mamie (Leila Bennett), a stereotypical maid character who shakes and screams at every shadow. The mixture of comedy and horror is typical of the old dark house genre, and here it works well to create the feeling of riding through a haunted house in a spinning car, laughing and screaming in equal measure as spooks jump out from every corner.

The most bizarre aspect of Doctor X is its wealth of crazed scientists, any one of whom might be the ghoulish Moon Killer. Early in the film, Doctor Xavier introduces the police to each of his employees in turn, and the audience shares the cops’ awe at the staggering assortment of suspects. Preston Foster, John Wray, Harry Beresford, and Arthur Edmund Carewe play the wild-eyed crew of researchers with great enthusiasm, and half the fun of the movie is picking one as the most likely suspect. Atwill’s Doctor Xavier also has a sinister edge, and the servant, Otto (George Rosener), is certainly creepy enough to warrant a spot on the list of potential cannibalistic killers.

See more of Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray in The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), which Michael Curtiz also directed. Best known today for high-profile classics like Casablanca (1942), Curtiz headed a handful of horror productions in the 1930s, including The Mad Genius (1931) and The Walking Dead (1936). Look for Lionel Atwill in Mark of the Vampire (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). Fay Wray screamed her way to lasting fame in King Kong (1933), but you’ll also find her in The Most Dangerous Game (1932). Catch fast-talking Pre-Code star Lee Tracy in Dinner at Eight (1933) and Bombshell (1933).

Friday, May 31, 2013

Tuesday, May 28, 2013

Event Report: Alabama Phoenix Festival 2013

Memorial Day weekend saw the arrival of the second annual Alabama Phoenix Festival in Birmingham, with three days of science fiction, fantasy, and general geekery for those inclined to enjoy such things. This is the kind of event that covers a lot of my interests, from classic sci-fi and horror films to popular culture icons, but this time I attended the convention in my LEGO fan guise, helping the Magic City LEGO Club with a large display that drew a lot of attention over the weekend.

Given that the convention is only in its second year, it managed to host an impressive guest list. Gil Gerard (BUCK ROGERS), Ernie Hudson (GHOSTBUSTERS), Colin Ferguson (EUREKA), and Janina Gavankar (TRUE BLOOD) were all on hand for panels and autographs, along with a bevy of authors, artists, and other professional guests. I was thrilled to find my popular culture colleagues, Dale Koontz and Ensley Guffey, at the convention to talk about the works of Joss Whedon. (Note to self: start going to cons as an author/scholar guest and geek out for free.) It turns out that Janina Gavankar is a huge LEGO fan, which made the weekend especially fun for our club folks.

A vendor area offered all kinds of goodies for sale, including toys, comics, jewelry, and books. In the author section, you could meet Allen Bellman, the Timely/Marvel comic book artist who worked on CAPTAIN AMERICA and other popular titles during the 1940s. Bellman had signed art for sale and was a big draw for classic comic book fans. Other fun attractions included a BACK TO THE FUTURE DeLorean, a large TARDIS replica, and a balloon artist who spent his weekend making elaborate versions of Slimer, Twiki, K-9, and even a huge balloon Dalek.

So what did I take to Phoenix Festival for the LEGO display? Digging deep into my childhood obsessions, I went with a Doctor Who themed LEGO creation. My "Whovian Holiday" layout featured classic Doctors like Patrick Troughton and Tom Baker as well as the new incarnations, their companions, and lots of enemies, including a small army of custom-built Daleks. I loved being able to build something like that for an audience that would actually recognize it; I usually hide the TARDIS in my show layouts, but only a few people pick up on the reference at our regular LEGO shows. (Note to self: start going to cons with the LEGO Doctor Who display and watch other people geek out.)

Overall, the convention was a great experience, and my daughter had an especially good time costume-watching and meeting other kids who share her peculiar set of interests (including a truly obsessive love for My Little Pony). One thing I would like to see at Phoenix Festival in the future is more attention to classic science fiction. Admittedly, GHOSTBUSTERS can be called a classic in certain circles, but it would have been nice to see some panels and events that celebrated the genre's long and glorious past. A lot of the youngsters in attendance could use the education. I did meet a lovely older man who was sporting a FRANKENSTEIN t-shirt the same day that I was wearing my Bela Lugosi DRACULA shirt, so I know there are some fans already built into the crowd. (Note to self: start going to cons to do panels on classic science fiction films and geek out while being attacked by giant leeches.)

If you're in the region and find Dragon Con too crowded these days, I do recommend a weekend at Alabama Phoenix Festival. I'll definitely be going back next year!

|

| Gil Gerard at Alabama Phoenix Festival |

|

| Balloon Dalek and K-9 by Doctor Osborn |

So what did I take to Phoenix Festival for the LEGO display? Digging deep into my childhood obsessions, I went with a Doctor Who themed LEGO creation. My "Whovian Holiday" layout featured classic Doctors like Patrick Troughton and Tom Baker as well as the new incarnations, their companions, and lots of enemies, including a small army of custom-built Daleks. I loved being able to build something like that for an audience that would actually recognize it; I usually hide the TARDIS in my show layouts, but only a few people pick up on the reference at our regular LEGO shows. (Note to self: start going to cons with the LEGO Doctor Who display and watch other people geek out.)

Overall, the convention was a great experience, and my daughter had an especially good time costume-watching and meeting other kids who share her peculiar set of interests (including a truly obsessive love for My Little Pony). One thing I would like to see at Phoenix Festival in the future is more attention to classic science fiction. Admittedly, GHOSTBUSTERS can be called a classic in certain circles, but it would have been nice to see some panels and events that celebrated the genre's long and glorious past. A lot of the youngsters in attendance could use the education. I did meet a lovely older man who was sporting a FRANKENSTEIN t-shirt the same day that I was wearing my Bela Lugosi DRACULA shirt, so I know there are some fans already built into the crowd. (Note to self: start going to cons to do panels on classic science fiction films and geek out while being attacked by giant leeches.)

If you're in the region and find Dragon Con too crowded these days, I do recommend a weekend at Alabama Phoenix Festival. I'll definitely be going back next year!

Monday, May 27, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: SUSANNAH OF THE MOUNTIES (1939)

Loosely adapted from a 1936 novel , Susannah of the Mounties (1939) is one of Shirley Temple's lesser films, particularly in comparison with her other 1939 film, The Little Princess. Both pictures came late in Temple's career as a child star and were directed by Walter Lang and William A. Seiter, but The Little Princess remains a favorite with her fans, while Susannah of the Mounties shows how thin the standard Temple plot had worn after so many similar pictures. Moreover, the film's insensitive, stereotyped depiction of the First Nations people of Canada makes it problematic for a modern audience, and children who see the movie will need to have an adult present to discuss its racial issues.

Temple stars as Susannah Sheldon, the only survivor of an Indian attack on a wagon train crossing the Canadian frontier. Taken in by a Mountie called Monty (Randolph Scott), Sue adapts to life with the Mounties and even makes friends with a chief's son (Martin Good Rider), but her new home is threatened by the outbreak of renewed hostilities.

The faults of the film do not lie with Temple, who gives a perfectly good performance as feisty Sue. In fact, Sue proves a rather interesting departure from some of the star's sugary sweet heroines; she is jealously attached to Monty and resents his budding romance with Vicky Standing (Margaret Lockwood). She also has a scrappy relationship with Little Chief, and her scenes with kindly old Pat (J. Farrell MacDonald) are fun, especially when she helps him keep his hairpiece on during an attack. She doesn't sing or dance much this time out, but her acting measures up to her usual standard.

The treatment of the native characters bears a lot in common with that seen in Peter Pan (1953), with a lot of stilted dialogue about "palefaces" with "forked tongues" punctuated with grunts. The chief, Big Eagle, is played by Jewish actor Maurice Moscovitch as a living cigar store statue, while swarthy Victor Jory, who was, at least, actually Canadian, plays the villainous Wolf Pelt. The film depicts native resistance to the settlers and the railroad as unreasonable, and the peace treaty reached at the end is really more a voluntary surrender on the part of the chief, a tacit acknowledgement that the whole conflict was just a foolish mistake on the part of the Indians. Cultural and racial problems of this kind pop up in many classic movies, of course, and they're even present in a lot of Temple's better films, but here there's little else going on to rescue the story from its dated imperialism. Canadians might also find fault with the film's version of the story as an American Western; there's really nothing about the movie that reflects its ostensible setting in a meaningful way.

For a more enjoyable Temple outing with cowboy star Randolph Scott, try Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1938). Margaret Lockwood appears in the Hitchcock thriller, The Lady Vanishes (1938), and in Carol Reed's Night Train to Munich (1940). You'll find character actor J. Farrell MacDonald in hundreds of small or uncredited roles; here at least he gets a number of good scenes. Walter Lang also directed Temple in The Blue Bird (1940), while William A. Seiter directed two of her 1936 films, Dimples and Stowaway. For more (and better) Shirley Temple pictures, try Heidi (1937), Wee Willie Winkie (1937), The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947), and Fort Apache (1948).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Temple stars as Susannah Sheldon, the only survivor of an Indian attack on a wagon train crossing the Canadian frontier. Taken in by a Mountie called Monty (Randolph Scott), Sue adapts to life with the Mounties and even makes friends with a chief's son (Martin Good Rider), but her new home is threatened by the outbreak of renewed hostilities.

The faults of the film do not lie with Temple, who gives a perfectly good performance as feisty Sue. In fact, Sue proves a rather interesting departure from some of the star's sugary sweet heroines; she is jealously attached to Monty and resents his budding romance with Vicky Standing (Margaret Lockwood). She also has a scrappy relationship with Little Chief, and her scenes with kindly old Pat (J. Farrell MacDonald) are fun, especially when she helps him keep his hairpiece on during an attack. She doesn't sing or dance much this time out, but her acting measures up to her usual standard.

The treatment of the native characters bears a lot in common with that seen in Peter Pan (1953), with a lot of stilted dialogue about "palefaces" with "forked tongues" punctuated with grunts. The chief, Big Eagle, is played by Jewish actor Maurice Moscovitch as a living cigar store statue, while swarthy Victor Jory, who was, at least, actually Canadian, plays the villainous Wolf Pelt. The film depicts native resistance to the settlers and the railroad as unreasonable, and the peace treaty reached at the end is really more a voluntary surrender on the part of the chief, a tacit acknowledgement that the whole conflict was just a foolish mistake on the part of the Indians. Cultural and racial problems of this kind pop up in many classic movies, of course, and they're even present in a lot of Temple's better films, but here there's little else going on to rescue the story from its dated imperialism. Canadians might also find fault with the film's version of the story as an American Western; there's really nothing about the movie that reflects its ostensible setting in a meaningful way.

For a more enjoyable Temple outing with cowboy star Randolph Scott, try Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1938). Margaret Lockwood appears in the Hitchcock thriller, The Lady Vanishes (1938), and in Carol Reed's Night Train to Munich (1940). You'll find character actor J. Farrell MacDonald in hundreds of small or uncredited roles; here at least he gets a number of good scenes. Walter Lang also directed Temple in The Blue Bird (1940), while William A. Seiter directed two of her 1936 films, Dimples and Stowaway. For more (and better) Shirley Temple pictures, try Heidi (1937), Wee Willie Winkie (1937), The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947), and Fort Apache (1948).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Monday, May 20, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: THE CHEYENNE SOCIAL CLUB (1970)

The names attached to The Cheyenne Social Club (1970) might reasonably give a viewer certain expectations of greatness, but director Gene Kelly's easy-going Western is content to let its stars, Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda, amble companionably through its mildly interesting plot, which takes the pair off the Texas range and into the well-appointed - if morally suspect - rooms of the title location. What we get as a result is a cowboy buddy movie compounded with a fish-out-of-water plot, nothing revolutionary or particularly ambitious, but amusing enough thanks to the two stars' natural camaraderie and the bustling good humor of the supporting actresses who play the social club's attractive commodities. This is by no means the best Western ever made by either actor, but those who appreciate the oaters Stewart and Fonda made earlier in their careers will probably enjoy this one, too, and those who know something about the stars' real-life friendship will like it even more.

Stewart plays John O'Hanlan, an aging Texas cowboy who unexpectedly inherits his dead brother's business in Cheyenne. Little suspecting the nature of his brother's establishment, John and his talkative sidekick, Harley Sullivan (Fonda), ride to Cheyenne to claim the inheritance. John is dismayed when The Cheyenne Social Club turns out to be a brothel, stocked with a bevy of attractive young women and headed up by Jenny (Shirley Jones) in the absence of the actual owner. Unfortunately, John finds it difficult to shut the place down, and he becomes embroiled in a series of deadly encounters when a local tough (Robert J. Wilke) beats Jenny.

O'Hanlan provides the fish-out-of-water theme, constantly stymied by the women, the townspeople, and the very idea of the brothel. His laconic, conservative nature contrasts with that of garrulous, free-wheeling Harley, who samples the ladies' wares with enthusiasm but balks at being drawn into O'Hanlan's fights. Stewart and Fonda invest these characters with completely credible cowhand personalities; both had made many Westerns in the earlier decades of their careers, and they know exactly the right way to ride a horse, handle a rifle, and chew or spit a line like a plug of tobacco. Their banter draws attention to the actors' long-standing friendship and the differences between them, especially in the realm of politics, but it does so without undermining the characters they're playing. Like Stewart and Fonda, John and Harley have a relationship that transcends their disagreements, even if they themselves don't always understand why.

The movie is technically a comedy, but it's not an uproarious one. The humor relies mostly on John's initial discomfort about the brothel and then his paternal attitude toward its denizens, with Harley's randy adventures with the girls providing some sense of a romp. Like other Westerns of its era, The Cheyenne Social Club reflects a genre in flux, trying to be several things at once in the wake of the traditional Western's slow demise. It falls back on a lot of classic Western motifs, but the brothel plot winks at the rise of the sex comedy and tries to make the picture hip for a younger and more sexually liberated audience. It doesn't necessarily succeed, but it has enough good nature to make up for many of its faults.

Gene Kelly is best remembered today as a song-and-dance actor, but in addition to The Cheyenne Social Club he also directed The Tunnel of Love (1958), A Guide for the Married Man (1967), and Hello, Dolly! (1969). His most successful films, however, were those he co-directed with Stanley Donen, including Singin' in the Rain (1952). Jimmy Stewart's first Western was Destry Rides Again (1939), but you'll also find him starring in a series of excellent oaters from Anthony Mann, particularly Winchester '73 (1950) and The Man from Laramie (1955). See The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and The Shootist (1976) for Stewart's late-career performances with cowboy icon John Wayne. Henry Fonda's early Westerns include Jesse James (1939), The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), and My Darling Clementine (1946), but he also makes an unusual foray into villainy in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). For more of Shirley Jones, see Oklahoma! (1955), Carousel (1956), and The Music Man (1962), as well as the television series, The Partridge Family. You can also see her with Jimmy Stewart in another Western, Two Rode Together (1961).

The Cheyenne Social Club is currently available on Warner Archive Instant and for $2.99 on Amazon Instant Video.

Stewart plays John O'Hanlan, an aging Texas cowboy who unexpectedly inherits his dead brother's business in Cheyenne. Little suspecting the nature of his brother's establishment, John and his talkative sidekick, Harley Sullivan (Fonda), ride to Cheyenne to claim the inheritance. John is dismayed when The Cheyenne Social Club turns out to be a brothel, stocked with a bevy of attractive young women and headed up by Jenny (Shirley Jones) in the absence of the actual owner. Unfortunately, John finds it difficult to shut the place down, and he becomes embroiled in a series of deadly encounters when a local tough (Robert J. Wilke) beats Jenny.

O'Hanlan provides the fish-out-of-water theme, constantly stymied by the women, the townspeople, and the very idea of the brothel. His laconic, conservative nature contrasts with that of garrulous, free-wheeling Harley, who samples the ladies' wares with enthusiasm but balks at being drawn into O'Hanlan's fights. Stewart and Fonda invest these characters with completely credible cowhand personalities; both had made many Westerns in the earlier decades of their careers, and they know exactly the right way to ride a horse, handle a rifle, and chew or spit a line like a plug of tobacco. Their banter draws attention to the actors' long-standing friendship and the differences between them, especially in the realm of politics, but it does so without undermining the characters they're playing. Like Stewart and Fonda, John and Harley have a relationship that transcends their disagreements, even if they themselves don't always understand why.

The movie is technically a comedy, but it's not an uproarious one. The humor relies mostly on John's initial discomfort about the brothel and then his paternal attitude toward its denizens, with Harley's randy adventures with the girls providing some sense of a romp. Like other Westerns of its era, The Cheyenne Social Club reflects a genre in flux, trying to be several things at once in the wake of the traditional Western's slow demise. It falls back on a lot of classic Western motifs, but the brothel plot winks at the rise of the sex comedy and tries to make the picture hip for a younger and more sexually liberated audience. It doesn't necessarily succeed, but it has enough good nature to make up for many of its faults.

Gene Kelly is best remembered today as a song-and-dance actor, but in addition to The Cheyenne Social Club he also directed The Tunnel of Love (1958), A Guide for the Married Man (1967), and Hello, Dolly! (1969). His most successful films, however, were those he co-directed with Stanley Donen, including Singin' in the Rain (1952). Jimmy Stewart's first Western was Destry Rides Again (1939), but you'll also find him starring in a series of excellent oaters from Anthony Mann, particularly Winchester '73 (1950) and The Man from Laramie (1955). See The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and The Shootist (1976) for Stewart's late-career performances with cowboy icon John Wayne. Henry Fonda's early Westerns include Jesse James (1939), The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), and My Darling Clementine (1946), but he also makes an unusual foray into villainy in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). For more of Shirley Jones, see Oklahoma! (1955), Carousel (1956), and The Music Man (1962), as well as the television series, The Partridge Family. You can also see her with Jimmy Stewart in another Western, Two Rode Together (1961).

The Cheyenne Social Club is currently available on Warner Archive Instant and for $2.99 on Amazon Instant Video.

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: THE BRIDE CAME C.O.D. (1941)

One does not generally think of Bette Davis as a comedienne, but The Bride Came C.O.D. (1941) provides a rare glimpse of the actress as a screwball heroine of the type more frequently played by Katharine Hepburn or Claudette Colbert. Directed by William Keighley and co-starring James Cagney, The Bride Came C.O.D. is not one of Davis' better known films or one of her best, but it's still a fun picture, especially because it offers such a different perspective on its two stars.

Davis plays oil heiress Joan Winfield, a spoiled rich girl whose whirlwind romance with a publicity-hungry band leader (Jack Carson) leads to an elopement. Joan's father (Eugene Pallette) opposes the match and accepts a deal with the couple's hired pilot, Steve Collins (James Cagney), to thwart the wedding. In order to keep Joan from tying the knot, Steve kidnaps her in his plane, but the two end up stranded in a desert ghost town where the only resident is an eccentric old man called Pop (Harry Davenport). Stuck with each other, Joan and Steve bicker their way toward romance, much to the amusement of Pop, but a widely publicized search for the missing bride makes Steve a wanted man.

In Dark Victory: The Life of Bette Davis, biographer Ed Sikov writes this movie off as "the worst screwball comedy ever made," but that's really an unfair assessment of the film. Davis looks great and seems to be having a wonderful time, and Cagney's own tremendous personality perfectly matches hers. It's a shame that they didn't make more films together. Admittedly, some of the gags wear thin by the movie's end; Bette Davis' rear seems magnetically attracted to every cactus in the desert, and the jokes about her weight won't get laughs from many female viewers. Davis does, however, get to cut loose for a change, and she and Cagney have the right chemistry for screwball romance. Cagney, of course, had more experience with comedy than his leading lady, and he also looks like he's enjoying himself quite a bit. He and Davis are both experts at salty, derisive dialogue and a well-timed, mocking laugh, and the relationship between Joan and Steve builds on these shared aspects of their temperaments.

Look for reliable character actors Eugene Pallette and William Frawley in supporting roles. Harry Davenport is very funny as Pop Tolliver, the crusty loner whose dilapidated hotel serves as a refuge for Joan and Steve. Davis and Cagney also star together in the 1934 film Jimmy the Gent, directed by Michael Curtiz. Contrast Davis' performance here with her better-known performances in Jezebel (1938), Dark Victory (1939), and All About Eve (1950). See classic Cagney in The Public Enemy (1931), Footlight Parade (1933), and Angels with Dirty Faces (1938). For more from director William Keighley, try The Prince and the Pauper (1937) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Davis plays oil heiress Joan Winfield, a spoiled rich girl whose whirlwind romance with a publicity-hungry band leader (Jack Carson) leads to an elopement. Joan's father (Eugene Pallette) opposes the match and accepts a deal with the couple's hired pilot, Steve Collins (James Cagney), to thwart the wedding. In order to keep Joan from tying the knot, Steve kidnaps her in his plane, but the two end up stranded in a desert ghost town where the only resident is an eccentric old man called Pop (Harry Davenport). Stuck with each other, Joan and Steve bicker their way toward romance, much to the amusement of Pop, but a widely publicized search for the missing bride makes Steve a wanted man.

In Dark Victory: The Life of Bette Davis, biographer Ed Sikov writes this movie off as "the worst screwball comedy ever made," but that's really an unfair assessment of the film. Davis looks great and seems to be having a wonderful time, and Cagney's own tremendous personality perfectly matches hers. It's a shame that they didn't make more films together. Admittedly, some of the gags wear thin by the movie's end; Bette Davis' rear seems magnetically attracted to every cactus in the desert, and the jokes about her weight won't get laughs from many female viewers. Davis does, however, get to cut loose for a change, and she and Cagney have the right chemistry for screwball romance. Cagney, of course, had more experience with comedy than his leading lady, and he also looks like he's enjoying himself quite a bit. He and Davis are both experts at salty, derisive dialogue and a well-timed, mocking laugh, and the relationship between Joan and Steve builds on these shared aspects of their temperaments.

Look for reliable character actors Eugene Pallette and William Frawley in supporting roles. Harry Davenport is very funny as Pop Tolliver, the crusty loner whose dilapidated hotel serves as a refuge for Joan and Steve. Davis and Cagney also star together in the 1934 film Jimmy the Gent, directed by Michael Curtiz. Contrast Davis' performance here with her better-known performances in Jezebel (1938), Dark Victory (1939), and All About Eve (1950). See classic Cagney in The Public Enemy (1931), Footlight Parade (1933), and Angels with Dirty Faces (1938). For more from director William Keighley, try The Prince and the Pauper (1937) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Seeing New York from the Outside: Woody Allen, THE GREAT GATSBY, and ON THE TOWN

I've had New York on my mind quite a bit lately. It started, I think, with a viewing of Woody Allen's Manhattan (1979), a movie in which the protagonist is more in love with the city than he is with any of the women in his life. Shot in black-and-white, the picture idealizes New York scenery (set against the inevitable strains of Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue"), and it seems as though its characters could never exist any place else. Mariel Hemingway's Tracy might depart for London at the end, but she remains a very New York sort of young woman, a product of liberal city life and the privileged halls of the Dalton School. Allen's own character is his typical, quintessential New Yorker, dubious about cars, apartments, and life outside the confines of the city. As the title of the film implies, it's really only and all about Manhattan.

Then I picked up the book my reading group had chosen for this month: The Great Gatsby. That carried me back into the fabled metropolis, this time as imagined by F. Scott Fitzgerald and his narrator, Nick Carraway. Of course the reading selection segued into a trip to see Baz Luhrmann's splashy new film adaptation, with its own gin-soaked vision of the Jazz Age city. Speakeasies and house parties, pollution and corruption - decadence sparkles in her ill-gotten goods, and New York is the place where the rise and fall happens. Nick, too, falls under the spell of the city; he hopes to make his own fortune there, even as he becomes drawn into the complicated fever dreams of Jay Gatsby. Near the end, Nick wonders if he and his peers are deficient in some way because they are "Westerners," but by "East" he means only New York and its environs. They are not New Yorkers, Nick and Gatsby, Daisy and Tom, and no amount of being there can erase their origins, no matter how much Gatsby tries to reinvent himself.

I am not a New Yorker, either, and I have only lately begun to ponder what Nick Carraway imagines as the "deficiency" of being from someplace else. As a child of the deep South I never even thought about New York, except perhaps as a place where movie stories are set, like L.A., only with more weather and no palm trees. They were both wholly imaginary places as far as I was concerned. My grandmother had lived there during World War II, and she gave birth to my uncle there, but her stories about wartime New York were about lonely apartments, illness, and the sympathetic neighbor women who worked in the munitions factories. They were not about "the city." I have spent more time in Paris, London, and Montreal than in New York. To date, my experience with NYC amounts to a single day when I was in college, with a morning spent having bagels with Bella Abzug and an afternoon in SoHo with northeastern friends who only wanted to buy drinks in tony bars.

This last year we started getting the Sunday edition of The New York Times, and reading it each week inspired the first glimmer of Nick Carraway's question in my own mind. What is New York to a non-New Yorker? What is a non-New Yorker to New York? The places I know so intimately - rural Southern towns and small cities, and sprawling, reborn Atlanta - don't appear much in the Times, except occasionally as the backdrops of seedy good ol' boy politics, shocking crimes, and cultural backwardness. Once in a while there's a play or an indie film filled with overdone accents and "local color." New York itself, on the other hand, shines like a star in the pages of the newspaper. It is a wonderland of film screenings, art galleries, museums, high fashion, and people who know how to appreciate them. It is awash in the contradictions of urban life - going on about environmental footprints and the smug superiority of not owning a car while planning fabulous vacations to Fiji and Sweden and shopping for swanky apartments that cost millions of dollars and involve small armies of "staff" to run. Nannies are a popular topic, as are the fears of parents desperate to get their children into the all-important Ivy League schools.

Once again, the city seems imaginary to me, mired as I am in a small Southern city where nobody I know has ever had a nanny and even poor people who live in trailer parks own cars of some sort or other. I could walk through the neighborhood and past the cow pasture to Target, I guess, but people would give me funny looks for it, and it would pretty much kill the afternoon. I'll be happy if my kid manages to go farther than Auburn or Alabama, but Yale? You might as well tell me she could move to the moon.

All of this contemplation brings me back around to the movies and my earlier question. What is New York to a non-New Yorker? To me, it's the city of On the Town (1949). That's a tourist's vision of a shining metropolis, a place to spend "just one day," as I did some 20 years ago. Hit the highlights, see the sights, and have a memorable experience in a place where you could never imagine yourself living, any more than you might live at Disneyland. (I did see a Hare Krishna parade, complete with an enormous brahma bull, in Washington Square Park.) On the Town is a non-New Yorker's movie about New York, which is why I like it so much. It's a postcard to America of a city most Americans never actually see. The insider movies, the Woody Allen films and the gritty dramas, like Taxi Driver and Do the Right Thing, mean less to me and speak of characters and lives that are alien, unfamiliar, unknowable. Often I actively dislike them. My favorite Allen films are the movie-obsessed fantasies - The Purple Rose of Cairo and Play It Again, Sam - because those are stories I understand from the inside.

America is so often reduced in our cultural imagination to just two cities - New York and Los Angeles. Sometimes San Francisco gets a nod. Most of us look at them from the outside, even though literature and film seem obsessed with an inward gaze. No wonder Nick feels deficient for being from the Midwest. Read The New York Times long enough and you might start to agree with him. I might go back to New York one day. I might not. I wonder how many visits it would take for On the Town to lose its charm and for Manhattan to make more sense. For now, the city remains a faraway place, a Neverland that sends me a newspaper once a week. It is a place, as Nick Carraway says, where "Anything can happen... even Gatsby could happen, without any particular wonder." Somebody cue "Rhapsody in Blue."

Then I picked up the book my reading group had chosen for this month: The Great Gatsby. That carried me back into the fabled metropolis, this time as imagined by F. Scott Fitzgerald and his narrator, Nick Carraway. Of course the reading selection segued into a trip to see Baz Luhrmann's splashy new film adaptation, with its own gin-soaked vision of the Jazz Age city. Speakeasies and house parties, pollution and corruption - decadence sparkles in her ill-gotten goods, and New York is the place where the rise and fall happens. Nick, too, falls under the spell of the city; he hopes to make his own fortune there, even as he becomes drawn into the complicated fever dreams of Jay Gatsby. Near the end, Nick wonders if he and his peers are deficient in some way because they are "Westerners," but by "East" he means only New York and its environs. They are not New Yorkers, Nick and Gatsby, Daisy and Tom, and no amount of being there can erase their origins, no matter how much Gatsby tries to reinvent himself.

I am not a New Yorker, either, and I have only lately begun to ponder what Nick Carraway imagines as the "deficiency" of being from someplace else. As a child of the deep South I never even thought about New York, except perhaps as a place where movie stories are set, like L.A., only with more weather and no palm trees. They were both wholly imaginary places as far as I was concerned. My grandmother had lived there during World War II, and she gave birth to my uncle there, but her stories about wartime New York were about lonely apartments, illness, and the sympathetic neighbor women who worked in the munitions factories. They were not about "the city." I have spent more time in Paris, London, and Montreal than in New York. To date, my experience with NYC amounts to a single day when I was in college, with a morning spent having bagels with Bella Abzug and an afternoon in SoHo with northeastern friends who only wanted to buy drinks in tony bars.

This last year we started getting the Sunday edition of The New York Times, and reading it each week inspired the first glimmer of Nick Carraway's question in my own mind. What is New York to a non-New Yorker? What is a non-New Yorker to New York? The places I know so intimately - rural Southern towns and small cities, and sprawling, reborn Atlanta - don't appear much in the Times, except occasionally as the backdrops of seedy good ol' boy politics, shocking crimes, and cultural backwardness. Once in a while there's a play or an indie film filled with overdone accents and "local color." New York itself, on the other hand, shines like a star in the pages of the newspaper. It is a wonderland of film screenings, art galleries, museums, high fashion, and people who know how to appreciate them. It is awash in the contradictions of urban life - going on about environmental footprints and the smug superiority of not owning a car while planning fabulous vacations to Fiji and Sweden and shopping for swanky apartments that cost millions of dollars and involve small armies of "staff" to run. Nannies are a popular topic, as are the fears of parents desperate to get their children into the all-important Ivy League schools.

Once again, the city seems imaginary to me, mired as I am in a small Southern city where nobody I know has ever had a nanny and even poor people who live in trailer parks own cars of some sort or other. I could walk through the neighborhood and past the cow pasture to Target, I guess, but people would give me funny looks for it, and it would pretty much kill the afternoon. I'll be happy if my kid manages to go farther than Auburn or Alabama, but Yale? You might as well tell me she could move to the moon.

All of this contemplation brings me back around to the movies and my earlier question. What is New York to a non-New Yorker? To me, it's the city of On the Town (1949). That's a tourist's vision of a shining metropolis, a place to spend "just one day," as I did some 20 years ago. Hit the highlights, see the sights, and have a memorable experience in a place where you could never imagine yourself living, any more than you might live at Disneyland. (I did see a Hare Krishna parade, complete with an enormous brahma bull, in Washington Square Park.) On the Town is a non-New Yorker's movie about New York, which is why I like it so much. It's a postcard to America of a city most Americans never actually see. The insider movies, the Woody Allen films and the gritty dramas, like Taxi Driver and Do the Right Thing, mean less to me and speak of characters and lives that are alien, unfamiliar, unknowable. Often I actively dislike them. My favorite Allen films are the movie-obsessed fantasies - The Purple Rose of Cairo and Play It Again, Sam - because those are stories I understand from the inside.

America is so often reduced in our cultural imagination to just two cities - New York and Los Angeles. Sometimes San Francisco gets a nod. Most of us look at them from the outside, even though literature and film seem obsessed with an inward gaze. No wonder Nick feels deficient for being from the Midwest. Read The New York Times long enough and you might start to agree with him. I might go back to New York one day. I might not. I wonder how many visits it would take for On the Town to lose its charm and for Manhattan to make more sense. For now, the city remains a faraway place, a Neverland that sends me a newspaper once a week. It is a place, as Nick Carraway says, where "Anything can happen... even Gatsby could happen, without any particular wonder." Somebody cue "Rhapsody in Blue."

Friday, May 10, 2013

Movie Lines We Live By

People love movie quotes in general, but sometimes lines from films become more than mere trivia items and evolve into part of the viewers' vocabulary, especially in groups where people have the same viewing history. In fan communities these lines become part of a code that denotes membership in the "inner circle" - people who can endlessly trade lines from Firefly, Doctor Who, or Star Trek recognize one another by the level of their knowledge. In more personal settings, however, the quoted lines can actually serve as a kind of shorthand communication between speakers: knowledge of both the source and the context is a given, and speakers are able to express a number of things at once, reinforcing the power and nuance of their shared experience.

I sometimes wonder what outsiders make of the conversations my husband and I have, since they are loaded with movie quotes that mean very particular things to us, and perhaps to us alone. We have been watching movies together for 22 years, more than 16 of those as a married couple. Along the way, we have collected enough movie lines that we could probably have an entire conversation composed of nothing else. The lines that become part of our vocabulary - a sort of cinematic "twin language" - reflect shared experience and interests, both personal and generational. In other words, we're a pair of Gen X geeks, and it definitely shows in the movies we quote to one another.

Here are some of the movie lines we live by, along with a little commentary about where they come from and what they mean to us.

"Chefs do that." - The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996)

Renny Harlin's noirish action picture stars Geena Davis as an assassin with amnesia; early in the picture she begins to recover some of her memories and forgotten skills, including some radical knife wielding abilities. My husband simply cannot pick up a knife in the kitchen without this line coming into play, but we also use it when one of us does something unexpected while cooking. Accidentally drop a plate and then catch it in mid-air? "Chefs do that." Almost lost a finger chopping broccoli? Ditto.

"Honestly... Who throws a shoe?" - Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997)

The actual line in the original Mike Myers spy spoof is reversed, but if either of us says "Honestly!" we are compelled by a deep-rooted psychological force to follow it with "Who throws a shoe?" It's a perfect expression of disbelief at a ridiculous event. The first Austin Powers movie is really quite a goldmine of domestic quotes, including "One MILLION dollars!" and "An EVIL petting zoo?"

"They told me they fixed it!... It's not my fault!" - The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

No self-respecting Gen X geek could get by without quoting Star Wars a couple of times a day, but in a domestic setting this line from Lando Calrissian proves especially handy. My husband tends to employ it most often whenever plumbers, carpenters, or car repairmen are involved, but computer technicians also inspire the line. When you expect something to work and it doesn't, it's time for the Lando line.

Other household favorites from the original trilogy include "I am not a committee!", "Would it help if I got out and pushed?", "I've got a bad feeling about this," "Would someone get this walking carpet out of my way?" and "I have altered the agreement. Pray I do not alter it further." We don't quote the prequel trilogy because that stuff is heresy. It would be like Baptists quoting the Book of Mormon.

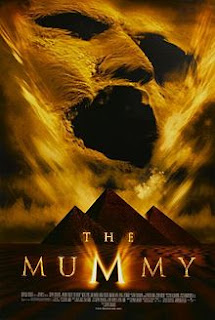

"You must not read from the book!" - The Mummy (1999)

I really couldn't tell you how many times we have watched Stephen Sommers' remake of the classic mummy movie, but it's enough that the dialogue has permanently embedded itself in our brains. Being a family of avid readers, we find a lot of use for this line about The Book of the Dead, but the film is full of gems that pop up regularly in our conversation. An icky corpse on a murder show often prompts, "Looks like you boys found yourselves a nice gooey mummy."

"She's a gasper!" - Rising Sun (1993)

My husband quotes this line, in a terrible Sean Connery impression, every time kinky sex is part of a plot on a TV show or film (or in the news). He can't help himself. In the original reference, the dead woman engaged in choking as part of bedroom play. For us, the line stands in for any crazy sex quirk, but of course the Connery impression only cements the idea of the act as ridiculous. At this point, I really don't remember that much about the movie, aside from it not being an especially good film, but this line will live on in our household vocabulary.

"Jesus, Grandpa! What did you read me this thing for?" - The Princess Bride (1987)

Of all the quotable lines in The Princess Bride - and there are dozens of them - this is the one that gets the most play at our house, primarily when one of us has suggested a film, TV show, or book that is a lot more violent or horrible than we expected. All one of us has to say is "Jesus, Grandpa!" and we know it's time to hit the stop button on the DVD player. It's also a handy line to communicate the inappropriate nature of a film or show for our kid - "No, I think that would end up being a 'Jesus Grandpa' experience. Let's skip it."

Runners-up from The Princess Bride include "Remember, this is for posterity, so be honest," often used when talking about how sick or injured one of us is, and "Get some rest. If you haven't got your health, you haven't got anything," which is a particular favorite in my conversations with my over-taxed BFF.

This list could go on for a long time, but I think you get the idea. I'll leave you with ten more of our favorite lines and their sources. In the comments section, feel free to tell me about some of the movie lines you live by!

"Cats and dogs living together...!" - Ghostbusters (1984)

"Cute plan, though." - Heist (2001)

"I like you, Clarence. Always have. Always will." - True Romance (1993)

"There's a snake in my boot!" - Toy Story (1995)

"The stars at night are big and bright - *clap clap clap* - deep in the heart of Texas!" - Pee-Wee's Big Adventure (1985)

"Two girls with green eyes!" - Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

"Snake Plissken... I heard you were dead!" - Escape from New York (1981)

"It's not a tumor!" - Kindergarten Cop (1999) *NB - We didn't even see this movie, and the line still stuck! Probably tied with "Consider this a divorce!" - Total Recall (1990) Both have to be uttered in the worst Arnold Schwarzenegger impression possible.

"Damn! We're in a tight spot!" - O Brother Where Art Thou?" (2000)

I sometimes wonder what outsiders make of the conversations my husband and I have, since they are loaded with movie quotes that mean very particular things to us, and perhaps to us alone. We have been watching movies together for 22 years, more than 16 of those as a married couple. Along the way, we have collected enough movie lines that we could probably have an entire conversation composed of nothing else. The lines that become part of our vocabulary - a sort of cinematic "twin language" - reflect shared experience and interests, both personal and generational. In other words, we're a pair of Gen X geeks, and it definitely shows in the movies we quote to one another.

Here are some of the movie lines we live by, along with a little commentary about where they come from and what they mean to us.

"Chefs do that." - The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996)

Renny Harlin's noirish action picture stars Geena Davis as an assassin with amnesia; early in the picture she begins to recover some of her memories and forgotten skills, including some radical knife wielding abilities. My husband simply cannot pick up a knife in the kitchen without this line coming into play, but we also use it when one of us does something unexpected while cooking. Accidentally drop a plate and then catch it in mid-air? "Chefs do that." Almost lost a finger chopping broccoli? Ditto.

"Honestly... Who throws a shoe?" - Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997)

The actual line in the original Mike Myers spy spoof is reversed, but if either of us says "Honestly!" we are compelled by a deep-rooted psychological force to follow it with "Who throws a shoe?" It's a perfect expression of disbelief at a ridiculous event. The first Austin Powers movie is really quite a goldmine of domestic quotes, including "One MILLION dollars!" and "An EVIL petting zoo?"

"They told me they fixed it!... It's not my fault!" - The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

No self-respecting Gen X geek could get by without quoting Star Wars a couple of times a day, but in a domestic setting this line from Lando Calrissian proves especially handy. My husband tends to employ it most often whenever plumbers, carpenters, or car repairmen are involved, but computer technicians also inspire the line. When you expect something to work and it doesn't, it's time for the Lando line.

Other household favorites from the original trilogy include "I am not a committee!", "Would it help if I got out and pushed?", "I've got a bad feeling about this," "Would someone get this walking carpet out of my way?" and "I have altered the agreement. Pray I do not alter it further." We don't quote the prequel trilogy because that stuff is heresy. It would be like Baptists quoting the Book of Mormon.

"You must not read from the book!" - The Mummy (1999)

I really couldn't tell you how many times we have watched Stephen Sommers' remake of the classic mummy movie, but it's enough that the dialogue has permanently embedded itself in our brains. Being a family of avid readers, we find a lot of use for this line about The Book of the Dead, but the film is full of gems that pop up regularly in our conversation. An icky corpse on a murder show often prompts, "Looks like you boys found yourselves a nice gooey mummy."

"She's a gasper!" - Rising Sun (1993)

My husband quotes this line, in a terrible Sean Connery impression, every time kinky sex is part of a plot on a TV show or film (or in the news). He can't help himself. In the original reference, the dead woman engaged in choking as part of bedroom play. For us, the line stands in for any crazy sex quirk, but of course the Connery impression only cements the idea of the act as ridiculous. At this point, I really don't remember that much about the movie, aside from it not being an especially good film, but this line will live on in our household vocabulary.

"Jesus, Grandpa! What did you read me this thing for?" - The Princess Bride (1987)

Of all the quotable lines in The Princess Bride - and there are dozens of them - this is the one that gets the most play at our house, primarily when one of us has suggested a film, TV show, or book that is a lot more violent or horrible than we expected. All one of us has to say is "Jesus, Grandpa!" and we know it's time to hit the stop button on the DVD player. It's also a handy line to communicate the inappropriate nature of a film or show for our kid - "No, I think that would end up being a 'Jesus Grandpa' experience. Let's skip it."

Runners-up from The Princess Bride include "Remember, this is for posterity, so be honest," often used when talking about how sick or injured one of us is, and "Get some rest. If you haven't got your health, you haven't got anything," which is a particular favorite in my conversations with my over-taxed BFF.

This list could go on for a long time, but I think you get the idea. I'll leave you with ten more of our favorite lines and their sources. In the comments section, feel free to tell me about some of the movie lines you live by!

"Cats and dogs living together...!" - Ghostbusters (1984)

"Cute plan, though." - Heist (2001)

"I like you, Clarence. Always have. Always will." - True Romance (1993)

"There's a snake in my boot!" - Toy Story (1995)

"The stars at night are big and bright - *clap clap clap* - deep in the heart of Texas!" - Pee-Wee's Big Adventure (1985)

"Two girls with green eyes!" - Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

"Snake Plissken... I heard you were dead!" - Escape from New York (1981)

"It's not a tumor!" - Kindergarten Cop (1999) *NB - We didn't even see this movie, and the line still stuck! Probably tied with "Consider this a divorce!" - Total Recall (1990) Both have to be uttered in the worst Arnold Schwarzenegger impression possible.

"Damn! We're in a tight spot!" - O Brother Where Art Thou?" (2000)

Monday, May 6, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: TORCH SONG (1953)

Television viewers of a certain age might remember Torch Song (1953) primarily as the butt of a spot-on parody on The Carol Burnett Show, in which Burnett offers a hilarious spin on Joan Crawford's performance in the classic melodrama. It's true that Torch Song, directed by Charles Walters, operates at a pitch that invites such skewering; women's pictures typically favor emotional excess, and Crawford has a particular talent for it, which is why she became such a huge star in that genre in the first place. If, however, you have a taste for weepies, there's a lot to enjoy in this film, not only in the troubled romance between the two leads but also in a number of solid supporting performances, including appearances by Harry Morgan, Gig Young, and Marjorie Rambeau.

Crawford stars as Broadway success Jenny Stewart, whose wealth and fame fail to protect her from years of bitter loneliness. Relentlessly demanding of everyone around her, Jenny finds herself in conflict with her new accompanist, a blind war veteran named Tye Graham (Michael Wilding). As she learns more about him, Jenny's feelings evolve, but his repressed anguish about his blindness keeps him from telling her how long he has loved her from afar.

As the plot summary suggests, there are untold stories that lurk behind the main plot of the film, and these stir the viewer's imagination and build sympathy with the central characters. We don't know how Tye Graham was blinded in the war, and we don't know what he has been doing all these years, although it was obviously enough to afford a very nice apartment. We only get a feeling about the toll that those same years have taken on Jenny; our idea of her as a young newcomer, fresh and lovely, flits around the edges of the story like a beautiful ghost of Broadway past. That idea lives primarily in the memory of Tye, who cannot see the older Jenny but can hear the strain in her voice and the deep-rooted unhappiness that inspires her harsh words. We also only get glimpses of Jenny's rocky relationship with her boyfriend, Cliff (Gig Young), but it's enough to convince us that neither of them is doing the other any real good.

Crawford's intensity fits perfectly with her character, who is so driven that she worries over every aspect of her play, from the costumes and the dance steps to the songs and the lights. The actress does not do her own singing in most of the picture, but her dancing, though somewhat limited, is more graceful and attractive than that seen in earlier work like Dancing Lady (1933). Her hair color at first seems an unfortunate choice, but, as it turns out, the color of her hair is an important plot point, and the less flattering shade functions as a provocative commentary on the way in which the aging Jenny resists the march of the years. Michael Wilding's mildness and blind stare as Tye contrast with Jenny's fierce temper and flashing eyes, and the two stars work well together, particularly in the climactic scene when their characters' roles are finally reversed.

Of the supporting players, Marjorie Rambeau merits special attention; she earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her performance as Jenny's blue-collar mother, who really loves her famous daughter even though she's not above pumping her for cash. Gig Young makes a likable if useless leech as Jenny's drunken playboy beau, and Harry Morgan reveals stores of long-suffering patience as the theater director who has to put up with Jenny's constant demands. Maidie Norman also puts in a fine performance as Jenny's household manager, who is not so much a maid as a personal assistant, and, apparently, one of the few people with whom Jenny actually behaves herself.

Charles Walters also directed Easter Parade (1948), High Society (1956), and The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964). For more of Joan Crawford's later roles, try The Damned Don't Cry (1950), Sudden Fear (1952), and Johnny Guitar (1954). By the end of the 1950s she was mostly doing television and hagsploitation horror like Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). See Michael Wilding in In Which We Serve (1942), Under Capricorn (1949), and Stage Fright (1950). Marjorie Rambeau also earned a Best Supporting Actress nomination for Primrose Path (1940), but she turns up in films going all the way back to 1917. You'll find Gig Young in Old Acquaintance (1943), The Three Musketeers (1948), and Desk Set (1957). Harry Morgan, best remembered for his role on M*A*S*H, has particularly memorable roles in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), High Noon (1952), and Inherit the Wind (1960), but he worked as a supporting player in many other films, especially Westerns.

Crawford stars as Broadway success Jenny Stewart, whose wealth and fame fail to protect her from years of bitter loneliness. Relentlessly demanding of everyone around her, Jenny finds herself in conflict with her new accompanist, a blind war veteran named Tye Graham (Michael Wilding). As she learns more about him, Jenny's feelings evolve, but his repressed anguish about his blindness keeps him from telling her how long he has loved her from afar.

As the plot summary suggests, there are untold stories that lurk behind the main plot of the film, and these stir the viewer's imagination and build sympathy with the central characters. We don't know how Tye Graham was blinded in the war, and we don't know what he has been doing all these years, although it was obviously enough to afford a very nice apartment. We only get a feeling about the toll that those same years have taken on Jenny; our idea of her as a young newcomer, fresh and lovely, flits around the edges of the story like a beautiful ghost of Broadway past. That idea lives primarily in the memory of Tye, who cannot see the older Jenny but can hear the strain in her voice and the deep-rooted unhappiness that inspires her harsh words. We also only get glimpses of Jenny's rocky relationship with her boyfriend, Cliff (Gig Young), but it's enough to convince us that neither of them is doing the other any real good.

Crawford's intensity fits perfectly with her character, who is so driven that she worries over every aspect of her play, from the costumes and the dance steps to the songs and the lights. The actress does not do her own singing in most of the picture, but her dancing, though somewhat limited, is more graceful and attractive than that seen in earlier work like Dancing Lady (1933). Her hair color at first seems an unfortunate choice, but, as it turns out, the color of her hair is an important plot point, and the less flattering shade functions as a provocative commentary on the way in which the aging Jenny resists the march of the years. Michael Wilding's mildness and blind stare as Tye contrast with Jenny's fierce temper and flashing eyes, and the two stars work well together, particularly in the climactic scene when their characters' roles are finally reversed.

Of the supporting players, Marjorie Rambeau merits special attention; she earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her performance as Jenny's blue-collar mother, who really loves her famous daughter even though she's not above pumping her for cash. Gig Young makes a likable if useless leech as Jenny's drunken playboy beau, and Harry Morgan reveals stores of long-suffering patience as the theater director who has to put up with Jenny's constant demands. Maidie Norman also puts in a fine performance as Jenny's household manager, who is not so much a maid as a personal assistant, and, apparently, one of the few people with whom Jenny actually behaves herself.

Charles Walters also directed Easter Parade (1948), High Society (1956), and The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964). For more of Joan Crawford's later roles, try The Damned Don't Cry (1950), Sudden Fear (1952), and Johnny Guitar (1954). By the end of the 1950s she was mostly doing television and hagsploitation horror like Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). See Michael Wilding in In Which We Serve (1942), Under Capricorn (1949), and Stage Fright (1950). Marjorie Rambeau also earned a Best Supporting Actress nomination for Primrose Path (1940), but she turns up in films going all the way back to 1917. You'll find Gig Young in Old Acquaintance (1943), The Three Musketeers (1948), and Desk Set (1957). Harry Morgan, best remembered for his role on M*A*S*H, has particularly memorable roles in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), High Noon (1952), and Inherit the Wind (1960), but he worked as a supporting player in many other films, especially Westerns.

Friday, May 3, 2013

Classic Films in Focus: REBECCA OF SUNNYBROOK FARM (1938)

For family friendly classic movies, it's hard to beat Shirley Temple's pictures. Admittedly, they follow a certain formula, but they're short, sweet, and often spiced with interesting supporting players. Directed by Allan Dwan, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm is an excellent example of the usual Temple set-up, although fans of the 1903 novel by Kate Douglas Wiggin will be disappointed by the movie's mere lip service to the original text. Even classic movie buffs who aren't particularly wild about Shirley Temple can enjoy Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm for its star-studded cast, which includes not only Randolph Scott and Gloria Stuart but also Jack Haley, Bill Robinson, and William Demarest.

Temple, of course, plays a sweet little girl in need of a home. This time she's Rebecca Winstead, initially under the suspect care of her stepfather, Uncle Harry (William Demarest), who tries to sell the kid into a show business contract during a radio contest. Harry pawns Rebecca off onto her aunt Miranda (Helen Westley) when he thinks his plans have failed, although radio executive Tony Kent (Randolph Scott) is really interested in having Rebecca on the air. Luckily, Tony's country retreat happens to be next door to Aunt Miranda's farm, which allows Rebecca to pursue her chance at stardom and promote a romance between Tony and her cousin, Gwen (Gloria Stuart).

Temple gives a reliably spunky, cute performance, with several song numbers and a nice dance routine with Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who appeared with her in several films. Jack Haley, best remembered today for his role as the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz (1939), doesn't dance this time but makes great use of his comic talent as Kent's bumbling assistant, and he does get to sing a bit. Gloria Stuart and Randolph Scott make fine romantic leads and prospective parents for the pint-sized heroine, and Scott has an especially affable charm once we move to the country scenes. Some romantic squabbling between Temple regular Helen Westley and lanky character actor Slim Summerville provides additional comic relief. The most surprising member of the cast might be William Demarest as Rebecca's oily, shiftless stepfather; he's not a very terrible villain, just a cupcake compared to some of Temple's female adversaries in other pictures, but his skill at the pratfall comes in handy, and he's certainly believable as a two-bit grifter.

For more films from Temple's heyday, try Stowaway (1936), Heidi (1937), and The Little Princess (1939). Cowboy star Randolph Scott played mostly in Westerns, including Jesse James (1939), The Tall T (1957) and Ride the High Country (1962), but he also appears with Temple in Susannah of the Mounties (1939). Gloria Stuart gained early fame for roles in films like The Invisible Man (1933) and then earned an Oscar nomination near the very end of her life for Titanic (1997). Look for William Demarest in celebrated classics like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Sullivan's Travels (1941), and The Lady Eve (1941). He earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor for The Jolson Story (1946) but gained more lasting fame for his role on the television series, My Three Sons. Director Allan Dwan, who had started out back in the silent era, also directed Heidi and the John Wayne war picture, Sands of Iwo Jima (1949).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Temple, of course, plays a sweet little girl in need of a home. This time she's Rebecca Winstead, initially under the suspect care of her stepfather, Uncle Harry (William Demarest), who tries to sell the kid into a show business contract during a radio contest. Harry pawns Rebecca off onto her aunt Miranda (Helen Westley) when he thinks his plans have failed, although radio executive Tony Kent (Randolph Scott) is really interested in having Rebecca on the air. Luckily, Tony's country retreat happens to be next door to Aunt Miranda's farm, which allows Rebecca to pursue her chance at stardom and promote a romance between Tony and her cousin, Gwen (Gloria Stuart).

Temple gives a reliably spunky, cute performance, with several song numbers and a nice dance routine with Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who appeared with her in several films. Jack Haley, best remembered today for his role as the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz (1939), doesn't dance this time but makes great use of his comic talent as Kent's bumbling assistant, and he does get to sing a bit. Gloria Stuart and Randolph Scott make fine romantic leads and prospective parents for the pint-sized heroine, and Scott has an especially affable charm once we move to the country scenes. Some romantic squabbling between Temple regular Helen Westley and lanky character actor Slim Summerville provides additional comic relief. The most surprising member of the cast might be William Demarest as Rebecca's oily, shiftless stepfather; he's not a very terrible villain, just a cupcake compared to some of Temple's female adversaries in other pictures, but his skill at the pratfall comes in handy, and he's certainly believable as a two-bit grifter.

For more films from Temple's heyday, try Stowaway (1936), Heidi (1937), and The Little Princess (1939). Cowboy star Randolph Scott played mostly in Westerns, including Jesse James (1939), The Tall T (1957) and Ride the High Country (1962), but he also appears with Temple in Susannah of the Mounties (1939). Gloria Stuart gained early fame for roles in films like The Invisible Man (1933) and then earned an Oscar nomination near the very end of her life for Titanic (1997). Look for William Demarest in celebrated classics like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Sullivan's Travels (1941), and The Lady Eve (1941). He earned an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor for The Jolson Story (1946) but gained more lasting fame for his role on the television series, My Three Sons. Director Allan Dwan, who had started out back in the silent era, also directed Heidi and the John Wayne war picture, Sands of Iwo Jima (1949).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.