Southern Gothic is all about collapse, moral, physical, and psychological, but it clings to its faded charms. It's a painted blush on a corpse's cheek, a courtly bow from the Grim Reaper, a wrinkled hag in a debutante gown. We understand the connection between decadence and decay in this sort of tale, dripping with Spanish moss and smiling cruelty. In Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), director Robert Aldrich brings all of these elements into play to create an intelligent horror movie for adults, those who can understand that the real terror lies as much in the sagging lines of Bette Davis' aging face as it does in the gruesome shadows of the summer house.

Davis plays Charlotte Hollis, the last remnant of a wealthy Louisiana family, who is stubbornly rotting away in her ancestral mansion, despite the fact that the government is about to tear the house down in order to build a bridge. She has her own reasons for clinging to her home, all stemming from the brutal murder of her lover (Bruce Dern) that took place there nearly forty years before. Everyone in town thinks that Charlotte did it, but of course there's a lot more to the story than that, and all of the long hidden details begin to seep out with the arrival of Charlotte's cousin, Miriam Deering (Olivia de Havilland). Soon the house is full of strange sights and sounds. Is Charlotte finally losing her mind, or is something sinister at work in the dark rooms of Hollis House?

The film brings Bette Davis full circle from Jezebel (1938), an idea hinted at in the portrait of a young Davis that decorates Hollis House in the later film. It is actually a painting of the star in her earlier role as Julie Marsden, and, indeed, Charlotte is a lot like what Julie might have become, brittle, stormy and willful, a difficult woman aging badly and at war with the world. The movie was meant to capitalize on the success of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) by reuniting stars Davis and Joan Crawford, but Crawford left just a few days into filming and was eventually replaced by Olivia de Havilland. The change was a boon to the film, since de Havilland makes for a much more interesting counterpoint to Davis, and it makes a wonderful ironic statement to have the angelic martyr of Gone with the Wind (1939) play Jezebel's duplicitous foil.

The other players hold their own against the two leading ladies. We get Joseph Cotten drawling away as the scheming Drew Bayliss, Agnes Moorehead feisty and hard-faced as Velma, Mary Astor as the dying Jewel Mayhew, and Cecil Kellaway as the kindly insurance agent, Harry. Bruce Dern looks suitably tragic and troubled as Charlotte's lover, John Mayhew, and Victor Buono is terrific as her overbearing father, Big Sam. Moorehead won a Golden Globe and was nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her part. Watch the studied lethargy she adopts whenever prying outsiders come around, the way she shifts her body language and facial expression between secret humane energy and assumed assumed insolent sloth.

Stunning visual compositions make full use of the black and white medium and suggest the themes and subtexts of the narrative. We see many instances of characters looking through windows or framed by windows and doors; the camera also emphasizes the opening and closing of doors in several key scenes. These images remind us how trapped Charlotte feels in Hollis House, but they also symbolize her imprisonment within her own mind; her antagonists make use of both of her prisons in their efforts to destroy her. Charlotte wanders through the faded rooms of the house at night, calling out for her murdered lover, herself a mere specter of the tragic girlish heroine she once had been. This house is definitely haunted, and the camera work builds our sense of dread beautifully, until we are fully prepared to be drawn into Charlotte's dreamlike vision of the ghostly party, where faceless revelers await the lovers' dance.

Nominated for seven Academy Awards, Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte is a rarity among horror films, although it has its peers in the likes of Gaslight (1944), Dragonwyck (1946), and The Night of the Hunter (1955). All of these Gothic thrillers have more in common with early horror than they do with the genre's modern incarnation. If you like goosebumps without gore, then these are the films for you. Try the sadly overlooked Lady in White (1988) for a modern revival of the classic Gothic style.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Classic Horror for Halloween

Halloween is the perfect time to enjoy classic horror from cinema's early days. These movies make great ambience enhancers during your annual costume party, but they're also good choices for an October evening's main entertainment. Here are ten horror classics to get you in the spirit for Halloween. Look for them on streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Instant Video, or Hulu.

Nosferatu (1922) - F.W. Murnau's silent and unofficial adaptation of Stoker's famous novel packs plenty of visual thrills. Max Schreck's hideous Count Orlok is still considered the scariest movie vampire by many film fans.

Dracula (1931) - Bela Lugosi stars as the iconic count in Tod Browning's very loose adaptation, but Dwight Frye steals the movie as the doomed madman Renfield. Edward Van Sloan also creates a definitive interpretation of the Van Helsing character.

Frankenstein (1931) - Boris Karloff creates the popular face of the man-made monster in James Whale's stylish treatment of Shelley's classic novel. Be sure to follow up with The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), featuring Elsa Lanchester as the iconic monster's mate.

The Mummy (1932) - Karl Freund directs as Karloff once again establishes an icon in this tragic story of eternal love. Fans of the 1999 treatment by Stephen Sommers absolutely need to see this original version to appreciate the later director's love for his source material.

The Wolf Man (1941) - George Waggner helms this production with Lon Chaney, Jr., as the title character; Bela Lugosi also appears as the gypsy werewolf who passes his curse to the unlucky Larry Talbot. Don't miss excellent performances from Claude Rains and Maria Ouspenskaya in the supporting roles.

Cat People (1942) - Under the auspices of Val Lewton, Jacques Tourneur directs this elegant variation on the werewolf theme, with Simone Simon as the tortured heroine. The swimming pool scene is justly regarded as one of the finest moments in classic horror history.

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) - This screwball comedy from Frank Capra is a Halloween staple for those who prefer lighter fare; Cary Grant stars as a newlywed whose dotty old aunts turn out to be homicidal maniacs. Look for Peter Lorre in a hilarious turn as the plastic surgeon who makes Mortimer Brewster's murderous brother (Raymond Massey) look like Boris Karloff!

Night of the Demon (1957) - Another Jacques Tourneur outing, this British horror classic stars Dana Andrews as a scientist who doubts the existence of the supernatural, even when he himself becomes its target. Peggy Cummins also stars, but Niall MacGinnis steals the picture as the sinister Dr. Karswell.

Eyes Without a Face (1960) - This French masterpiece from Georges Franju delivers dreamlike horror as a guilt-ridden surgeon tries to replace his daughter's hideously disfigured face by stealing replacements from other young women. Edith Scob stars as the disfigured heroine, with Pierre Brasseur as her obsessed father and Alida Valli as his faithful accomplice.

The Haunting (1963) - Robert Wise's terrifying adaptation of Shirley Jackson's novel offers plenty of thrills without the gore for those who like their horror on the psychological side. Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, and Russ Tamblyn star as the unfortunate visitors who rouse the house's malevolent spirit.

Looking for even more classic horror? Check out all of the posts under the "horror" label, including full-length reviews of most of these films. You'll also find plenty of classic horror films in my book, Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching, now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.com.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Nosferatu (1922) - F.W. Murnau's silent and unofficial adaptation of Stoker's famous novel packs plenty of visual thrills. Max Schreck's hideous Count Orlok is still considered the scariest movie vampire by many film fans.

Dracula (1931) - Bela Lugosi stars as the iconic count in Tod Browning's very loose adaptation, but Dwight Frye steals the movie as the doomed madman Renfield. Edward Van Sloan also creates a definitive interpretation of the Van Helsing character.

Frankenstein (1931) - Boris Karloff creates the popular face of the man-made monster in James Whale's stylish treatment of Shelley's classic novel. Be sure to follow up with The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), featuring Elsa Lanchester as the iconic monster's mate.

The Mummy (1932) - Karl Freund directs as Karloff once again establishes an icon in this tragic story of eternal love. Fans of the 1999 treatment by Stephen Sommers absolutely need to see this original version to appreciate the later director's love for his source material.

The Wolf Man (1941) - George Waggner helms this production with Lon Chaney, Jr., as the title character; Bela Lugosi also appears as the gypsy werewolf who passes his curse to the unlucky Larry Talbot. Don't miss excellent performances from Claude Rains and Maria Ouspenskaya in the supporting roles.

Cat People (1942) - Under the auspices of Val Lewton, Jacques Tourneur directs this elegant variation on the werewolf theme, with Simone Simon as the tortured heroine. The swimming pool scene is justly regarded as one of the finest moments in classic horror history.

|

| Edith Scob stars in Eyes without a Face (1960). |

Night of the Demon (1957) - Another Jacques Tourneur outing, this British horror classic stars Dana Andrews as a scientist who doubts the existence of the supernatural, even when he himself becomes its target. Peggy Cummins also stars, but Niall MacGinnis steals the picture as the sinister Dr. Karswell.

Eyes Without a Face (1960) - This French masterpiece from Georges Franju delivers dreamlike horror as a guilt-ridden surgeon tries to replace his daughter's hideously disfigured face by stealing replacements from other young women. Edith Scob stars as the disfigured heroine, with Pierre Brasseur as her obsessed father and Alida Valli as his faithful accomplice.

The Haunting (1963) - Robert Wise's terrifying adaptation of Shirley Jackson's novel offers plenty of thrills without the gore for those who like their horror on the psychological side. Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, and Russ Tamblyn star as the unfortunate visitors who rouse the house's malevolent spirit.

Looking for even more classic horror? Check out all of the posts under the "horror" label, including full-length reviews of most of these films. You'll also find plenty of classic horror films in my book, Beyond Casablanca: 100 Classic Movies Worth Watching, now available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.com.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

The Gothic Influences of Disney's Haunted Mansion

My good friend, James Graham, presented this paper at the Popular Culture Association in the South conference in September, and I thought it was much too interesting to be confined to that small audience. I asked him to share the paper here at Virtual Virago because I know a lot of people will enjoy reading about the beloved ride's history and its connections to a number of iconic horror films.

Without further prelude, here is "Welcome Foolish Mortals." Enjoy!

Welcome Foolish Mortals: The Gothic Influences of Disney's Haunted Mansion

Guest Post by James Graham

A brief for the uninitiated: The Haunted Mansion is a dark ride, a “haunted house”-style attraction at Disney theme parks. Guests board ride vehicles (termed “doom buggies”) and travel through creepy, kooky, and campy vignettes loosely organized into a three-act structure. First built over forty years ago and periodically renovated to take advantage of emerging special-effects technology, versions of the attraction exist in Disneyland, Walt Disney World, Tokyo, and Paris.

In 1948 Walt Disney began to envision his first theme park, a modest 8-acre plot he called “Mickey Park.” The heart and entrance to the park was to be the brightly lit Main Street U.S.A., with a city hall, fire and police stations, opera house, music store, encircling train, and one aspect he felt no American town should be without, ghosts. Over the next few years his ideas grew and the project moved from the Burbank studio lot to a spacious 160 acres in Anaheim he would later dub “the happiest place on earth.” The name had changed to Disneyland, but Main Street remained the entrance and many of Walt’s original ideas grew to become the four themed “lands” within the larger park: Adventure, Frontier, Fantasy, and Tomorrow.

Disney’s plans, however, full of light and fantasy and wonder, still also included a sketch of a lonely and foreboding ruin on the outskirts of the park. Walt believed that every proper American town should have at least one haunted house. Nevertheless, the park opened in 1955 without its ghosts, and Walt did not live to see the attraction completed. More years passed before the mansion would open its doors to the public, during which time the Disney imagineers disagreed as to the direction Walt would have taken had he lived.

Walt Disney’s management strategy for the design of his haunted house was both acquisitive and hands-off: he would rob other departments of their best artists and idea men, throw them into a partnership with a few other like-minded conscripts, and set them loose with an unlimited budget, infinite space, and no definite calendar. Each group, seemingly regardless of their beliefs regarding the direction the ride should finally take, was told they were doing well and that Disney himself saw the merit in their approach.

The teams would visit each other and work on similar concepts, but would pull projects from other teams at will and reedit them into new directions. Because of the encouragement from above, each crew believed that they and they alone had Disney’s master goal in mind.

One such group was led by the original concept artists: Harper Goff, Ken Anderson, Marvin Davis, and Sam McKim. Responsible for the original concept sketches in 1951, these men worked on the project when it was still thought of as a walk-thru attraction, a large manor with regularly guided tours like the real-life Sara Winchester house or Hearst Castle at San Simeon. Nevertheless, many of the features they envisioned still found a home in the finished attraction twenty years later.

A second group was led by special-effects wizard and imagineer Yale Gracey and his collaborator, artist Rolly Crump. To achieve the most frightening tour they could imagine, they tirelessly worked and reworked a detailed script involving a ship’s captain, his murdered bride, and the ghosts of multiple violent homicides. A combination of cutting-edge 1960’s hardware and 19th century stagecraft, less than a quarter of what they worked on for a decade accounted for 90% of the special effects of the completed ride.

Imagineer and former animator Marc Davis (largely responsible for the success of Pirates of the Carribean) produced hundreds of watercolor sketches for the decidedly ride-thru attraction. His volumes of concept art include nearly all of the character-driven gags that make up the last two thirds of the ride. Davis and David Schweninger (who built all the audio-animatronic figures) worked hard to make their contribution a light-hearted collection of scenes that would be funny, not frightening. Davis always felt that the end product was still much too dark for Disney.

Team four consisted of former background artists Claude Coates and Collin Campbell. Coates’ atmospheric and frightening concept paintings ultimately became the settings for Davis’ silly spooks, while Collin Campbell retouched Davis’s art and merged the two portfolios, one daffy, one dreary, into creepy room-by-room images.

While still more imagineers hammered out the mechanics of the complicated new ride vehicles, occupancy, loading times, architecture, and scenery, one very crucial team hit upon a unifying solution. Xavier Atencio and Buddy Baker created a script that was a true compromise in that it pleased no one. Too silly for some and too terrifying for others, their plan was to introduce the guests to an indifferent host and unseen, uncanny threats, then gradually introduce the spirits and lighten the mood, until the finale in a ghost-a-palooza graveyard scene that is all whacky fun.

Tying it all together is Buddy Baker’s score—as a slow dirge, a waltz, or with X. Atencio’s lyrics as the swinging “Grim Grinning Ghosts.” The melody follows the guests through the ride, giving a sense of unity and swooping all around the musical scale but deliberately avoiding what Baker and Atencio saw as a musical “cliché” in 1960’s films of using tritones or the “Devil’s interval” to jar or scare the listener with a musical cue.

Books and fan websites like doombuggies.com devote a great deal of space to the individual efforts of these and other imagineers, documenting which man or woman was responsible for which aspect of the finished product and speaking to the lasting influence of The Haunted Mansion upon our popular culture.

What has intrigued me, however, is the question “What sorts of media influenced them in their creation of the ride?” In some cases the sources are readily apparent, others require digging to identify, and at least one example is (so far) purely conjectural, as we shall see.

What follows is a partial list of Gothic influences upon the creators of The Haunted Mansion, not to pick apart the masterwork attraction as an unoriginal work, but to use the ride as a lens or time-capsule to see what was popular in the Gothic during the decade of the rides’ construction, between 1960 and 1970.

Edgar Allan Poe

“The Raven”—talking raven guide

Evident in some of the unused early recordings and a talking character in the “story and song” album, a squawking (but nonverbal) raven (or his shadow) still follows guests through several scenes. One abandoned concept featured the cat or raven as a wicked familiar working against the ghost host to either save or doom the guests.

“The Black Cat”—talking one-eyed cat guide

Evident in some of the unused early recordings, the cat can be seen in many early concept sketches and his caterwauling can still be heard in the background of several scenes. One abandoned concept featured the cat or raven as a wicked familiar working against the ghost host to either save or doom the guests.

“The Pit and the Pendulum”

The story features an escape-proof room whose shape and dimensions silently change on the narrator to force him into the pit.

Anticipates the stretching portrait gallery with “no windows and no doors,” where suicide is the suggested “exit.”

The aforementioned chamber in the story has devils literally painted on the walls that are not visible until the chamber is heated/the lighting changes.

Anticipates some of the basic “shifting” effects in the Haunted Mansion

“The Premature Burial”

The conservatory includes a coffin whose occupant is trying to leave.

“The Black Cat” and “The Cask of Amontillado”

A crypt in the cemetery has a the arm of a skeleton attempting to finish walling himself in.

“The Tell-Tale Heart”

The effects in the attic were originally syncopated to the beating of the bride’s heart, including the appearance and disappearance of the “hat-box ghost’s” head.

The WDW attraction is described specifically in promotional material for its’ 1971 opening as “the Edgar Allan Poe-style 'Haunted Mansion'”.

Oscar Wilde - The Picture of Dorian Gray

The portrait in the foyer rapidly ages to a decaying skeleton before the eyes of guests.

Félicien Rops

Friend and part of a mutual admiration society with Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, Rops’ 1883 black and white illustration “The Supreme Vice” seems a partial inspiration for the popular (but rarely seen) pair of original attic occupants, the “hat-box ghost” and his bride.

Roger Corman

Corman is partly known for the popular cycle of six Poe-inspired films he directed (1960-1964), most starring Vincent Price:

1960 House of Usher

1961 The Pit and the Pendulum

1962 The Premature Burial

1963 The Raven

1964 The Masque of the Red Death

1964 The Tomb of Ligeia

The Raven (1963)

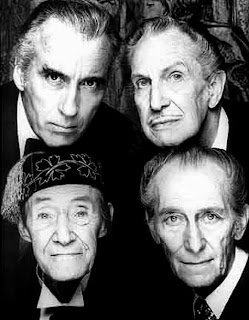

The film stars Boris Karloff, Vincent Price, and Peter Lorre as a wizard transformed into a talking raven.

Of unused ideas and paths not taken on the RedDot album, one is a piece of “ghost-host” narration done in imitation of Peter Lorre. [Another is as Bela Lugosi]

In the “Grim Grinning Ghosts” sequence at the end of the finished ride, a ten-second verse (on one loop of the spiel) is still sung in imitation of Boris Karloff.

[Coincidentally, not long before his death Vincent Price was hired to record an (unused) unique narration for Phantom Manor, the Disneyland Paris analogue to the Haunted Mansion]

(also on the RedDot album)

The Haunting (1963)

Robert Wise film, based on Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

a very similar "breathing" door terrorizes guests

also like the “door corridor,” menacing, pounding sounds intimidate the visitors to Hill House

A compromise, The Haunted Mansion still shows traces of the conflicting pulls of the disparate teams. By reflecting the varied interests of each squabbling group, the ride can be read as a snapshot of what was big in the Gothic during the early 1960’s.

Some found inspiration in the macabre tales of Poe and Wilde, designing premature burials and portraits that aged before the viewer’s eyes. Some thought the public needed the pounding, breathing mansion of Shirley Jackson’s novel of contemporary terror The Haunting of Hill House (and its film adaptation). Others thought the ride should be campy fun, with tongue-in-cheek horror and talking ravens as in the Poe-inspired films of Roger Corman. A fourth and final camp had naturally assumed the attraction was derived from Disney’s 1937 Animated short “Lonesome Ghosts,” and thought it should be limited to the all-ages fun of a Mickey Mouse cartoon.

While some of the imagineers drew upon older Gothic literary sources or the Disney animated archives, it is clear that several idea men were influenced by the modern Gothic films in the cinemas at the time. It is these still-visible Gothic influences that make The Haunted Mansion a uniquely chilling and amusing entertainment.

Without further prelude, here is "Welcome Foolish Mortals." Enjoy!

Welcome Foolish Mortals: The Gothic Influences of Disney's Haunted Mansion

Guest Post by James Graham

A brief for the uninitiated: The Haunted Mansion is a dark ride, a “haunted house”-style attraction at Disney theme parks. Guests board ride vehicles (termed “doom buggies”) and travel through creepy, kooky, and campy vignettes loosely organized into a three-act structure. First built over forty years ago and periodically renovated to take advantage of emerging special-effects technology, versions of the attraction exist in Disneyland, Walt Disney World, Tokyo, and Paris.

In 1948 Walt Disney began to envision his first theme park, a modest 8-acre plot he called “Mickey Park.” The heart and entrance to the park was to be the brightly lit Main Street U.S.A., with a city hall, fire and police stations, opera house, music store, encircling train, and one aspect he felt no American town should be without, ghosts. Over the next few years his ideas grew and the project moved from the Burbank studio lot to a spacious 160 acres in Anaheim he would later dub “the happiest place on earth.” The name had changed to Disneyland, but Main Street remained the entrance and many of Walt’s original ideas grew to become the four themed “lands” within the larger park: Adventure, Frontier, Fantasy, and Tomorrow.

Disney’s plans, however, full of light and fantasy and wonder, still also included a sketch of a lonely and foreboding ruin on the outskirts of the park. Walt believed that every proper American town should have at least one haunted house. Nevertheless, the park opened in 1955 without its ghosts, and Walt did not live to see the attraction completed. More years passed before the mansion would open its doors to the public, during which time the Disney imagineers disagreed as to the direction Walt would have taken had he lived.

Walt Disney’s management strategy for the design of his haunted house was both acquisitive and hands-off: he would rob other departments of their best artists and idea men, throw them into a partnership with a few other like-minded conscripts, and set them loose with an unlimited budget, infinite space, and no definite calendar. Each group, seemingly regardless of their beliefs regarding the direction the ride should finally take, was told they were doing well and that Disney himself saw the merit in their approach.

The teams would visit each other and work on similar concepts, but would pull projects from other teams at will and reedit them into new directions. Because of the encouragement from above, each crew believed that they and they alone had Disney’s master goal in mind.

One such group was led by the original concept artists: Harper Goff, Ken Anderson, Marvin Davis, and Sam McKim. Responsible for the original concept sketches in 1951, these men worked on the project when it was still thought of as a walk-thru attraction, a large manor with regularly guided tours like the real-life Sara Winchester house or Hearst Castle at San Simeon. Nevertheless, many of the features they envisioned still found a home in the finished attraction twenty years later.

A second group was led by special-effects wizard and imagineer Yale Gracey and his collaborator, artist Rolly Crump. To achieve the most frightening tour they could imagine, they tirelessly worked and reworked a detailed script involving a ship’s captain, his murdered bride, and the ghosts of multiple violent homicides. A combination of cutting-edge 1960’s hardware and 19th century stagecraft, less than a quarter of what they worked on for a decade accounted for 90% of the special effects of the completed ride.

Imagineer and former animator Marc Davis (largely responsible for the success of Pirates of the Carribean) produced hundreds of watercolor sketches for the decidedly ride-thru attraction. His volumes of concept art include nearly all of the character-driven gags that make up the last two thirds of the ride. Davis and David Schweninger (who built all the audio-animatronic figures) worked hard to make their contribution a light-hearted collection of scenes that would be funny, not frightening. Davis always felt that the end product was still much too dark for Disney.

Team four consisted of former background artists Claude Coates and Collin Campbell. Coates’ atmospheric and frightening concept paintings ultimately became the settings for Davis’ silly spooks, while Collin Campbell retouched Davis’s art and merged the two portfolios, one daffy, one dreary, into creepy room-by-room images.

While still more imagineers hammered out the mechanics of the complicated new ride vehicles, occupancy, loading times, architecture, and scenery, one very crucial team hit upon a unifying solution. Xavier Atencio and Buddy Baker created a script that was a true compromise in that it pleased no one. Too silly for some and too terrifying for others, their plan was to introduce the guests to an indifferent host and unseen, uncanny threats, then gradually introduce the spirits and lighten the mood, until the finale in a ghost-a-palooza graveyard scene that is all whacky fun.

Tying it all together is Buddy Baker’s score—as a slow dirge, a waltz, or with X. Atencio’s lyrics as the swinging “Grim Grinning Ghosts.” The melody follows the guests through the ride, giving a sense of unity and swooping all around the musical scale but deliberately avoiding what Baker and Atencio saw as a musical “cliché” in 1960’s films of using tritones or the “Devil’s interval” to jar or scare the listener with a musical cue.

Books and fan websites like doombuggies.com devote a great deal of space to the individual efforts of these and other imagineers, documenting which man or woman was responsible for which aspect of the finished product and speaking to the lasting influence of The Haunted Mansion upon our popular culture.

What has intrigued me, however, is the question “What sorts of media influenced them in their creation of the ride?” In some cases the sources are readily apparent, others require digging to identify, and at least one example is (so far) purely conjectural, as we shall see.

What follows is a partial list of Gothic influences upon the creators of The Haunted Mansion, not to pick apart the masterwork attraction as an unoriginal work, but to use the ride as a lens or time-capsule to see what was popular in the Gothic during the decade of the rides’ construction, between 1960 and 1970.

Edgar Allan Poe

“The Raven”—talking raven guide

Evident in some of the unused early recordings and a talking character in the “story and song” album, a squawking (but nonverbal) raven (or his shadow) still follows guests through several scenes. One abandoned concept featured the cat or raven as a wicked familiar working against the ghost host to either save or doom the guests.

“The Black Cat”—talking one-eyed cat guide

Evident in some of the unused early recordings, the cat can be seen in many early concept sketches and his caterwauling can still be heard in the background of several scenes. One abandoned concept featured the cat or raven as a wicked familiar working against the ghost host to either save or doom the guests.

“The Pit and the Pendulum”

The story features an escape-proof room whose shape and dimensions silently change on the narrator to force him into the pit.

Anticipates the stretching portrait gallery with “no windows and no doors,” where suicide is the suggested “exit.”

The aforementioned chamber in the story has devils literally painted on the walls that are not visible until the chamber is heated/the lighting changes.

Anticipates some of the basic “shifting” effects in the Haunted Mansion

“The Premature Burial”

The conservatory includes a coffin whose occupant is trying to leave.

“The Black Cat” and “The Cask of Amontillado”

A crypt in the cemetery has a the arm of a skeleton attempting to finish walling himself in.

“The Tell-Tale Heart”

The effects in the attic were originally syncopated to the beating of the bride’s heart, including the appearance and disappearance of the “hat-box ghost’s” head.

The WDW attraction is described specifically in promotional material for its’ 1971 opening as “the Edgar Allan Poe-style 'Haunted Mansion'”.

Oscar Wilde - The Picture of Dorian Gray

The portrait in the foyer rapidly ages to a decaying skeleton before the eyes of guests.

Félicien Rops

Friend and part of a mutual admiration society with Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, Rops’ 1883 black and white illustration “The Supreme Vice” seems a partial inspiration for the popular (but rarely seen) pair of original attic occupants, the “hat-box ghost” and his bride.

Roger Corman

Corman is partly known for the popular cycle of six Poe-inspired films he directed (1960-1964), most starring Vincent Price:

1960 House of Usher

1961 The Pit and the Pendulum

1962 The Premature Burial

1963 The Raven

1964 The Masque of the Red Death

1964 The Tomb of Ligeia

The Raven (1963)

The film stars Boris Karloff, Vincent Price, and Peter Lorre as a wizard transformed into a talking raven.

Of unused ideas and paths not taken on the RedDot album, one is a piece of “ghost-host” narration done in imitation of Peter Lorre. [Another is as Bela Lugosi]

In the “Grim Grinning Ghosts” sequence at the end of the finished ride, a ten-second verse (on one loop of the spiel) is still sung in imitation of Boris Karloff.

[Coincidentally, not long before his death Vincent Price was hired to record an (unused) unique narration for Phantom Manor, the Disneyland Paris analogue to the Haunted Mansion]

(also on the RedDot album)

The Haunting (1963)

Robert Wise film, based on Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

a very similar "breathing" door terrorizes guests

also like the “door corridor,” menacing, pounding sounds intimidate the visitors to Hill House

A compromise, The Haunted Mansion still shows traces of the conflicting pulls of the disparate teams. By reflecting the varied interests of each squabbling group, the ride can be read as a snapshot of what was big in the Gothic during the early 1960’s.

Some found inspiration in the macabre tales of Poe and Wilde, designing premature burials and portraits that aged before the viewer’s eyes. Some thought the public needed the pounding, breathing mansion of Shirley Jackson’s novel of contemporary terror The Haunting of Hill House (and its film adaptation). Others thought the ride should be campy fun, with tongue-in-cheek horror and talking ravens as in the Poe-inspired films of Roger Corman. A fourth and final camp had naturally assumed the attraction was derived from Disney’s 1937 Animated short “Lonesome Ghosts,” and thought it should be limited to the all-ages fun of a Mickey Mouse cartoon.

While some of the imagineers drew upon older Gothic literary sources or the Disney animated archives, it is clear that several idea men were influenced by the modern Gothic films in the cinemas at the time. It is these still-visible Gothic influences that make The Haunted Mansion a uniquely chilling and amusing entertainment.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Classic Films in Focus: DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1941)

Like Dracula and Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde serves as a touchstone for literary and cinematic horror. Directed by Victor Fleming, the 1941 film is one of many screen adaptations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic tale of the id unleashed, and like most movies it takes certain liberties with its source material. Although it is not generally regarded as the best film version to tackle the text, the 1941 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde remains worth watching today primarily for its impressive A-list cast, which includes not only Spencer Tracy in the dual title role but Ingrid Bergman and Lana Turner as two love interests who attract both the monster and the man.

Tracy leads as Dr. Henry Jekyll, whose engagement to the angelic Beatrix (Lana Turner) is jeopardized by his obsessive efforts to separate the good and evil sides of human nature. Determined to pursue his research, Jekyll becomes his own test subject and thereby sets loose his darker half, Hyde, on the city of London. Sadistically cruel and unfettered by Jekyll’s better nature, Hyde ensnares a barmaid named Ivy (Ingrid Bergman) as his unwilling mistress and soon threatens everyone whom his alter ego holds dear.

Tracy’s performance as both Jekyll and Hyde is interesting if not great. The Oscar-winning actor certainly had better roles over the course of his career, but his intense, burning eyes and hard-edged mouth suggest the powerful beast within even when he’s playing the more humane doctor. Film buffs more frequently note the performances of his lovely costars, largely because the two actresses swapped roles before filming began. Bergman was originally chosen to play the saintly Bea, while Turner was to have the bad girl role. Having claimed the the more compelling part, Bergman’s performance is perhaps the most nuanced and moving of the entire film, although you won’t buy her attempt at an English accent for a second.

The sexual themes of the film don’t lurk beneath the surface; they burst out at the seams, charging every interaction between the central characters. Jekyll’s relationship with Beatrix mixes barely repressed desire with utter disregard for her feelings and expectations; he already loves his research more than he loves her as the story begins, and his transformation into the more openly selfish and destructive Hyde is anything but a surprise after that. In one particularly memorable scene, a hallucinating Hyde lashes a pair of horses, one light and the other dark, while the horses transform into the tormented figures of Ivy and Bea.

It’s a tribute to Stevenson’s creative influence that so many other film treatments of this tale have been done over the decades. See the 1931 version with Fredric March to compare the two casts and their approaches to the major characters; the consensus is that March gives the superior performance in the dual title roles. John Barrymore also offers an interpretation of the man and monster in the silent 1920 adaptation. For a different take on the story, try Mary Reilly (1996) or even The Nutty Professor (1963). The duality of the Jekyll/Hyde character continues to fascinate audiences and filmmakers; we see new versions of the story every few years, but the Tracy and March adaptations do much to help shape these later productions.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde earned three Oscar nominations but went home empty-handed from the 1942 awards. See Captains Courageous (1937) and Boys Town (1938) for Spencer Tracy’s Oscar-winning roles; he was nominated a total of nine times for Best Actor. Ingrid Bergman earned seven nominations with three wins, although she was not nominated for her most famous role as Humphrey Bogart’s lost love in Casablanca (1942). Lana Turner earned her only Oscar nomination for Peyton Place (1957), but she is best remembered today for her femme fatale role in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). Don’t miss veteran actor Donald Crisp as Bea’s worried father; a silent film star who played Ulysses S. Grant in D.W. Griffith’s landmark film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), Crisp weathered the transition to talkies and won his own Best Supporting Actor award for How Green Was My Valley (1941).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Tracy leads as Dr. Henry Jekyll, whose engagement to the angelic Beatrix (Lana Turner) is jeopardized by his obsessive efforts to separate the good and evil sides of human nature. Determined to pursue his research, Jekyll becomes his own test subject and thereby sets loose his darker half, Hyde, on the city of London. Sadistically cruel and unfettered by Jekyll’s better nature, Hyde ensnares a barmaid named Ivy (Ingrid Bergman) as his unwilling mistress and soon threatens everyone whom his alter ego holds dear.

Tracy’s performance as both Jekyll and Hyde is interesting if not great. The Oscar-winning actor certainly had better roles over the course of his career, but his intense, burning eyes and hard-edged mouth suggest the powerful beast within even when he’s playing the more humane doctor. Film buffs more frequently note the performances of his lovely costars, largely because the two actresses swapped roles before filming began. Bergman was originally chosen to play the saintly Bea, while Turner was to have the bad girl role. Having claimed the the more compelling part, Bergman’s performance is perhaps the most nuanced and moving of the entire film, although you won’t buy her attempt at an English accent for a second.

The sexual themes of the film don’t lurk beneath the surface; they burst out at the seams, charging every interaction between the central characters. Jekyll’s relationship with Beatrix mixes barely repressed desire with utter disregard for her feelings and expectations; he already loves his research more than he loves her as the story begins, and his transformation into the more openly selfish and destructive Hyde is anything but a surprise after that. In one particularly memorable scene, a hallucinating Hyde lashes a pair of horses, one light and the other dark, while the horses transform into the tormented figures of Ivy and Bea.

It’s a tribute to Stevenson’s creative influence that so many other film treatments of this tale have been done over the decades. See the 1931 version with Fredric March to compare the two casts and their approaches to the major characters; the consensus is that March gives the superior performance in the dual title roles. John Barrymore also offers an interpretation of the man and monster in the silent 1920 adaptation. For a different take on the story, try Mary Reilly (1996) or even The Nutty Professor (1963). The duality of the Jekyll/Hyde character continues to fascinate audiences and filmmakers; we see new versions of the story every few years, but the Tracy and March adaptations do much to help shape these later productions.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde earned three Oscar nominations but went home empty-handed from the 1942 awards. See Captains Courageous (1937) and Boys Town (1938) for Spencer Tracy’s Oscar-winning roles; he was nominated a total of nine times for Best Actor. Ingrid Bergman earned seven nominations with three wins, although she was not nominated for her most famous role as Humphrey Bogart’s lost love in Casablanca (1942). Lana Turner earned her only Oscar nomination for Peyton Place (1957), but she is best remembered today for her femme fatale role in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). Don’t miss veteran actor Donald Crisp as Bea’s worried father; a silent film star who played Ulysses S. Grant in D.W. Griffith’s landmark film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), Crisp weathered the transition to talkies and won his own Best Supporting Actor award for How Green Was My Valley (1941).

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Classic Films in Focus: MARK OF THE VAMPIRE (1935)

Like Dracula's Daughter (1936), Mark of the Vampire (1935) plays out as a kind of semi-sequel to Dracula (1931), even though this Tod Browning picture was made for MGM rather than Universal. The movie reunites Browning with his Dracula star, Bela Lugosi, but it also stocks the screen with a bevy of other memorable stars, including Lionel Barrymore, Jean Hersholt, Lionel Atwill, and Donald Meek. The film suffers from plot holes made worse by the studio's decision to cut several scenes, and today it is not nearly as well known as its iconic predecessor, but fans of the horror genre and classic star watchers will find Mark of the Vampire interesting enough because of its cast and the ways in which it looks back at the 1931 original.

The story revolves around the murder of Sir Karell (Holmes Herbert), who is found drained of blood with two small marks on his neck. The locals blame two vampires, Count Mora (Bela Lugosi) and Luna (Carroll Borland), who are said to haunt the neighborhood castle. When Sir Karell's daughter, Irena (Elizabeth Allan), and her suitor, Fedor (Henry Wadsworth), are also attacked, an occult expert (Lionel Barrymore) is called in to hunt down the undead creatures, but the truth is both stranger and more earthly than it first appears.

Top-billed Lionel Barrymore doesn't actually make his appearance in the film until twenty minutes in, but his Professor Zelen takes over the Van Helsing role, played by Barrymore as a sort of old time politician with lots of posturing and self-conscious gestures. If he hams it up a bit too much, at least it helps him hold the screen against Hersholt, Atwill, and Lugosi, all of whom are far more interesting than the story's dull romantic leads. The scene stealer of the bunch, however, is newcomer Carroll Borland, who looks terrific with her pale face, staring eyes, and flowing white shroud. Her attacks on Irena recall J. Sheridan Le Fanu's predatory Carmilla and provide some of the best images of the picture.

Despite the effective Gothic atmosphere and unusual vampire effects that Browning builds up in the first part of the film, he ultimately opts for a Radcliffean model of Gothic narrative that reveals the appearance of the supernatural as mere facade. While that allows for a smirking coda of comedy with Lugosi and Borland, it also creates huge problems with the logic of the events that have already occurred. Viewers will end up asking a lot of questions that simply have no answers, although some of them, perhaps, were addressed in the missing scenes that MGM cut out. Why, for example, does Count Mora sport a ghastly wound on his temple? How do the vampires fly in and out of second story rooms? At least the ending does help us understand why a household under attack from supposed vampires keeps opening all of its windows and doors at night.

Mark of the Vampire is no masterpiece, certainly, but at only 60 minutes long it repays the time spent on it with an entertaining look at some truly iconic Hollywood stars. For more of Browning's work with Lionel Barrymore, see The Devil-Doll (1936). You'll find Barrymore and Hersholt in both Grand Hotel (1932) and Dinner at Eight (1933). Lionel Atwill, a genre regular, turns up in horror classics like The Vampire Bat (1933), Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). See more of Bela himself in White Zombie (1932), The Wolf Man (1941), and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

The story revolves around the murder of Sir Karell (Holmes Herbert), who is found drained of blood with two small marks on his neck. The locals blame two vampires, Count Mora (Bela Lugosi) and Luna (Carroll Borland), who are said to haunt the neighborhood castle. When Sir Karell's daughter, Irena (Elizabeth Allan), and her suitor, Fedor (Henry Wadsworth), are also attacked, an occult expert (Lionel Barrymore) is called in to hunt down the undead creatures, but the truth is both stranger and more earthly than it first appears.

Top-billed Lionel Barrymore doesn't actually make his appearance in the film until twenty minutes in, but his Professor Zelen takes over the Van Helsing role, played by Barrymore as a sort of old time politician with lots of posturing and self-conscious gestures. If he hams it up a bit too much, at least it helps him hold the screen against Hersholt, Atwill, and Lugosi, all of whom are far more interesting than the story's dull romantic leads. The scene stealer of the bunch, however, is newcomer Carroll Borland, who looks terrific with her pale face, staring eyes, and flowing white shroud. Her attacks on Irena recall J. Sheridan Le Fanu's predatory Carmilla and provide some of the best images of the picture.

Despite the effective Gothic atmosphere and unusual vampire effects that Browning builds up in the first part of the film, he ultimately opts for a Radcliffean model of Gothic narrative that reveals the appearance of the supernatural as mere facade. While that allows for a smirking coda of comedy with Lugosi and Borland, it also creates huge problems with the logic of the events that have already occurred. Viewers will end up asking a lot of questions that simply have no answers, although some of them, perhaps, were addressed in the missing scenes that MGM cut out. Why, for example, does Count Mora sport a ghastly wound on his temple? How do the vampires fly in and out of second story rooms? At least the ending does help us understand why a household under attack from supposed vampires keeps opening all of its windows and doors at night.

Mark of the Vampire is no masterpiece, certainly, but at only 60 minutes long it repays the time spent on it with an entertaining look at some truly iconic Hollywood stars. For more of Browning's work with Lionel Barrymore, see The Devil-Doll (1936). You'll find Barrymore and Hersholt in both Grand Hotel (1932) and Dinner at Eight (1933). Lionel Atwill, a genre regular, turns up in horror classics like The Vampire Bat (1933), Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). See more of Bela himself in White Zombie (1932), The Wolf Man (1941), and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

Friday, October 26, 2012

Classic Films in Focus: THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1957)

Although Mary Shelley's novel has been filmed many times, every adaptation of Frankenstein is unique, a point that The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) helps to prove. Director Terence Fisher's version of the Frankenstein story offers a different take than the iconic 1931 picture from James Whale; it brings in more Gothic atmosphere and revels in an early opportunity for full color gore. With Hammer stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee in the roles of the scientist and his monster, The Curse of Frankenstein has great appeal for fans of classic horror, and its deviations from the source material offer some fascinating commentary on the cultural evolution of Shelley's modern Prometheus.

Cushing plays Baron Victor Frankenstein, who comes into his title and his wealth at an early age and uses the opportunity to hire himself a tutor with expert qualifications in science. His chosen mentor is Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), who teaches the younger man everything he knows but eventually grows uncomfortable with the direction of Victor's research. Consumed by his desire to create life, Victor ignores his intended bride, Elizabeth (Hazel Court), although he does find time to carry on a callous affair with the resident maid, Justine (Valerie Gaunt). Eventually, Victor's efforts bring the Monster (Christopher Lee) into being, but the master cannot control his creation, despite numerous operations to alter the creature's brain.

Peter Cushing makes an excellent Frankenstein; he perfectly conveys the sneering narcissism of the aristocracy and looks both incredibly intelligent and insufferably aware of it. The character of Paul is created as a foil to Victor, and Robert Urquhart has an open, sincere expression that marks him as Victor's opposite; both men are technically scientists, but Paul imagines science as a way to help humanity, while Victor sees it as a path to godlike power. The two women also function as foils to one another; Hazel Court's Elizabeth is utterly innocent, unable to imagine that Victor might be capable of wrong, while Valerie Gaunt's Justine is a jealous schemer who attempts to blackmail Victor into marrying her. Both women mistake the character of their man, but Justine pays the steeper price for the error. There's a terrible irony in Victor's decision to let the monster destroy Justine after she reveals that she is pregnant with his child; he is choosing one kind of offspring over another, an act that symbolizes his rejection of the entire natural world. This is not the death that Justine suffered in Shelley's novel, but it fits with the film's interpretation of Victor's character and drives home the point that Shelley makes about the protagonist as a figure of paternal failure.

When he finally appears, Christopher Lee's creature reveals an appearance more zombie than golem, with a green, decayed face and one pale, clouded eye, but like Karloff's character he lacks the powers of thought and speech. An early scene in which Victor describes the beautiful hands he has stolen for his creature helps to explain why Lee's own elegant, tapered fingers extend from his sleeves while his heavily made-up face presents such a mockery of human expression. He's certainly harder to look at than Karloff, but he's also more fragile and pathetic, especially after Victor resurrects him for a second time and begins carving up his already damaged brain. The lion's share of the story belongs to Cushing's amoral, ambitious Victor, but Lee does his best with his limited role, although it would have been interesting for Hammer to hew more closely to Shelley's novel and let Lee's tremendously eloquent intelligence inhabit that patchwork frame. A year later, Horror of Dracula (1958) would offer the pair more evenly matched opponents with Cushing as Van Helsing and Lee as the bloodthirsty count.

For more of classic Cushing and Lee, go on to Horror of Dracula and then to The Mummy (1959). Both enjoyed long careers with particularly good roles late in life; look for Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977) and Lee as Saruman in The Lord of the Rings trilogy and as Count Dooku in the Star Wars prequels. You'll find Robert Urquhart as Gawaine in Knights of the Round Table (1953), but he had better success with television than he did in films. Scream queen Hazel Court appears in The Raven (1962) and several other Roger Corman horror films. Hammer fans might appreciate the Turner Classic Movies DVD set that includes The Curse of Frankenstein as well as Horror of Dracula, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Cushing plays Baron Victor Frankenstein, who comes into his title and his wealth at an early age and uses the opportunity to hire himself a tutor with expert qualifications in science. His chosen mentor is Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), who teaches the younger man everything he knows but eventually grows uncomfortable with the direction of Victor's research. Consumed by his desire to create life, Victor ignores his intended bride, Elizabeth (Hazel Court), although he does find time to carry on a callous affair with the resident maid, Justine (Valerie Gaunt). Eventually, Victor's efforts bring the Monster (Christopher Lee) into being, but the master cannot control his creation, despite numerous operations to alter the creature's brain.

Peter Cushing makes an excellent Frankenstein; he perfectly conveys the sneering narcissism of the aristocracy and looks both incredibly intelligent and insufferably aware of it. The character of Paul is created as a foil to Victor, and Robert Urquhart has an open, sincere expression that marks him as Victor's opposite; both men are technically scientists, but Paul imagines science as a way to help humanity, while Victor sees it as a path to godlike power. The two women also function as foils to one another; Hazel Court's Elizabeth is utterly innocent, unable to imagine that Victor might be capable of wrong, while Valerie Gaunt's Justine is a jealous schemer who attempts to blackmail Victor into marrying her. Both women mistake the character of their man, but Justine pays the steeper price for the error. There's a terrible irony in Victor's decision to let the monster destroy Justine after she reveals that she is pregnant with his child; he is choosing one kind of offspring over another, an act that symbolizes his rejection of the entire natural world. This is not the death that Justine suffered in Shelley's novel, but it fits with the film's interpretation of Victor's character and drives home the point that Shelley makes about the protagonist as a figure of paternal failure.

When he finally appears, Christopher Lee's creature reveals an appearance more zombie than golem, with a green, decayed face and one pale, clouded eye, but like Karloff's character he lacks the powers of thought and speech. An early scene in which Victor describes the beautiful hands he has stolen for his creature helps to explain why Lee's own elegant, tapered fingers extend from his sleeves while his heavily made-up face presents such a mockery of human expression. He's certainly harder to look at than Karloff, but he's also more fragile and pathetic, especially after Victor resurrects him for a second time and begins carving up his already damaged brain. The lion's share of the story belongs to Cushing's amoral, ambitious Victor, but Lee does his best with his limited role, although it would have been interesting for Hammer to hew more closely to Shelley's novel and let Lee's tremendously eloquent intelligence inhabit that patchwork frame. A year later, Horror of Dracula (1958) would offer the pair more evenly matched opponents with Cushing as Van Helsing and Lee as the bloodthirsty count.

For more of classic Cushing and Lee, go on to Horror of Dracula and then to The Mummy (1959). Both enjoyed long careers with particularly good roles late in life; look for Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977) and Lee as Saruman in The Lord of the Rings trilogy and as Count Dooku in the Star Wars prequels. You'll find Robert Urquhart as Gawaine in Knights of the Round Table (1953), but he had better success with television than he did in films. Scream queen Hazel Court appears in The Raven (1962) and several other Roger Corman horror films. Hammer fans might appreciate the Turner Classic Movies DVD set that includes The Curse of Frankenstein as well as Horror of Dracula, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Reflections on Classic Horror

Years ago, I attempted to teach a unit on horror to a class of college freshmen. It was an unmitigated disaster. We watched the 1941 Universal horror classic, The Wolf Man, in class, and the students complained as though they had all been scheduled with lengthy dentist appointments. Their objections were endless: it wasn't scary, it was too slow, it was in (gasp!) black and white! After the movie they suggested that their primitive ancestors might have found The Wolf Man scary because people didn't know anything about good special effects then, or because, way back in 1941, people still believed in werewolves.

Yes, they actually said that, and, yes, I wept for the future. The anecdote suggests the need to answer some questions about classic horror movies. Are they supposed to be scary? What did the people who saw them when they were new think about them? Why don't we find them scary today?

It's important to dispel the whole "ignorance of good special effects" myth right away. Early filmmakers saw their medium as a bold frontier, and anything was possible. They were capable of creating dazzling effects without a single computer. I can think of no better example than the winged monkeys of The Wizard of Oz (1939). They have continued to terrify children and disturb adults for seventy years. Margaret Hamilton's Wicked Witch of the West is pretty darn scary, too, but those monkeys just give people the chills.

Granted, The Wizard of Oz is not technically a horror film, but what about Nosferatu (1922), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and Freaks (1932)? The first two films use incredible make-up effects to create unparalleled spectacles of deformity, while the third one skips the whole idea of artifice and shows us the real thing. One can certainly argue that some films have not fared as well, and their effects can look dated to the sophisticated twenty-first century eye, but many early films reveal a level of creativity rarely seen in movies today, and it's clear that they could and did put make-up, costuming, and effects of all kinds to very good use.

What did the original viewers think? People passed out in droves at the first screenings of Eyes Without a Face (1960), much to the director's delight, and the makers of Freaks were sued by one woman who claimed that the film had caused her to have a miscarriage. As a whole, people enjoyed horror movies, but certainly not because they believed that Dracula, the Mummy, the Wolf Man, and Frankenstein's monster were real. Partly they loved the actors who disappeared into those fascinating roles, and partly they loved the fun of a harmless thrill.

They wanted to be pleasurably frightened, but they did not want to be traumatized or assaulted by what they saw. With World War II and plenty of visceral horror out in the real world, people of that era didn't seem to feel any need to see the minutiae of human anatomy dissected for them on screen. There's a now famous scene in Frankenstein (1931), in which the monster drowns a little girl, that was cut from the final release version of the film. It was considered too awful for people to see; it represented a line that the film could not cross without losing its original audience. Clearly, the threshold for what constituted the horrific was much lower then than it is today.

Even more important is the fact that early horror films simply rely on a different aesthetic and dramatic foundation than most modern examples of the genre. The roots of these films lie in the nineteenth century, in the Romantic and Gothic literary movements, where the idea of terror exists in tandem with beauty and awe. It's no accident that both Frankenstein and Dracula were novels from this period long before they were films, and other movies drew their material from works by Edgar Allan Poe, Victor Hugo, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

The key concept here is that of the "sublime," in which subjects are drawn to things that evoke both terror and awe, like mountains, oceans, and vast deserts. In early horror, the monsters and supernatural events become the embodiments of the sublime; they both fascinate and terrify, attract and repel. It's this understanding of the sublime and its psychological force that makes The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) so brilliant.

Furthermore, the early films borrow psychological complexity from their literary forebears; characters struggle against their monstrosity, grappling with destiny itself, and in doing so they symbolize the universal experience of inner conflict. William Godwin had done a very good job illustrating this struggle in Caleb Williams way back in 1794, but we see it worked out beautifully in horror classics like Dracula's Daughter (1936), The Wolf Man (1941), and Cat People (1942), just to name a few.

Classic horror films do not, in general, bludgeon the viewer with their terrors; they brush against the psyche with the subtlety of a moth's wing. They are less scary, perhaps, but they are more elegant and thoughtful. I am very fond of quite a few modern horror films, but the ones I like take their cues from the classics. True horror fans appreciate those early films as well as their descendants, and they understand that terror can take many different forms, not merely that of a disfigured maniac wielding a large, sharp weapon. Those old movies reveal their macabre charms to the viewer who is wise enough to see them.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Yes, they actually said that, and, yes, I wept for the future. The anecdote suggests the need to answer some questions about classic horror movies. Are they supposed to be scary? What did the people who saw them when they were new think about them? Why don't we find them scary today?

It's important to dispel the whole "ignorance of good special effects" myth right away. Early filmmakers saw their medium as a bold frontier, and anything was possible. They were capable of creating dazzling effects without a single computer. I can think of no better example than the winged monkeys of The Wizard of Oz (1939). They have continued to terrify children and disturb adults for seventy years. Margaret Hamilton's Wicked Witch of the West is pretty darn scary, too, but those monkeys just give people the chills.

Granted, The Wizard of Oz is not technically a horror film, but what about Nosferatu (1922), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and Freaks (1932)? The first two films use incredible make-up effects to create unparalleled spectacles of deformity, while the third one skips the whole idea of artifice and shows us the real thing. One can certainly argue that some films have not fared as well, and their effects can look dated to the sophisticated twenty-first century eye, but many early films reveal a level of creativity rarely seen in movies today, and it's clear that they could and did put make-up, costuming, and effects of all kinds to very good use.

What did the original viewers think? People passed out in droves at the first screenings of Eyes Without a Face (1960), much to the director's delight, and the makers of Freaks were sued by one woman who claimed that the film had caused her to have a miscarriage. As a whole, people enjoyed horror movies, but certainly not because they believed that Dracula, the Mummy, the Wolf Man, and Frankenstein's monster were real. Partly they loved the actors who disappeared into those fascinating roles, and partly they loved the fun of a harmless thrill.

They wanted to be pleasurably frightened, but they did not want to be traumatized or assaulted by what they saw. With World War II and plenty of visceral horror out in the real world, people of that era didn't seem to feel any need to see the minutiae of human anatomy dissected for them on screen. There's a now famous scene in Frankenstein (1931), in which the monster drowns a little girl, that was cut from the final release version of the film. It was considered too awful for people to see; it represented a line that the film could not cross without losing its original audience. Clearly, the threshold for what constituted the horrific was much lower then than it is today.

Even more important is the fact that early horror films simply rely on a different aesthetic and dramatic foundation than most modern examples of the genre. The roots of these films lie in the nineteenth century, in the Romantic and Gothic literary movements, where the idea of terror exists in tandem with beauty and awe. It's no accident that both Frankenstein and Dracula were novels from this period long before they were films, and other movies drew their material from works by Edgar Allan Poe, Victor Hugo, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

The key concept here is that of the "sublime," in which subjects are drawn to things that evoke both terror and awe, like mountains, oceans, and vast deserts. In early horror, the monsters and supernatural events become the embodiments of the sublime; they both fascinate and terrify, attract and repel. It's this understanding of the sublime and its psychological force that makes The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) so brilliant.

Furthermore, the early films borrow psychological complexity from their literary forebears; characters struggle against their monstrosity, grappling with destiny itself, and in doing so they symbolize the universal experience of inner conflict. William Godwin had done a very good job illustrating this struggle in Caleb Williams way back in 1794, but we see it worked out beautifully in horror classics like Dracula's Daughter (1936), The Wolf Man (1941), and Cat People (1942), just to name a few.

Classic horror films do not, in general, bludgeon the viewer with their terrors; they brush against the psyche with the subtlety of a moth's wing. They are less scary, perhaps, but they are more elegant and thoughtful. I am very fond of quite a few modern horror films, but the ones I like take their cues from the classics. True horror fans appreciate those early films as well as their descendants, and they understand that terror can take many different forms, not merely that of a disfigured maniac wielding a large, sharp weapon. Those old movies reveal their macabre charms to the viewer who is wise enough to see them.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Classic Films in Focus: THE RAVEN (1963)

The Raven is certainly one of the most famous poems ever written in the English language, and it has earned a particular place of honor in the realm of popular culture, where everyone from John Carradine and James Earl Jones to John De Lancie and Christopher Walken has recorded a version of its irresistible lines. Roger Corman's loose adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's iconic poem is more a lark than an "ominous bird of yore," but that won't stop fans of the poem or the horror director's work from enjoying this funny, star-studded horror-comedy.

Vincent Price stars as Dr. Erasmus Craven, a scholarly magician whose nightly studies are interrupted when a large raven seeks admittance to his home. The bird turns out to be Dr. Bedlo (Peter Lorre), another practitioner of the dark arts. Along with their respective offspring, Bedlo and Craven make a journey to the castle of a rival sorcerer, Dr. Scarabus (Boris Karloff), where the magicians enter into a deadly contest of supernatural skill.

While the stars of the film are some of horror's most prolific masters, The Raven relies primarily on comedy for its effect. The performers all seem to be having a good time, although Peter Lorre's hangdog looks and hilarious dialogue make him a real scene-stealer. Any viewer with an affection for Price, Lorre, and Karloff will enjoy this romp, although it's best to come at the picture with an expectation of campy pleasures rather than credible thrills. Scream queen Hazel Court plays Craven's supposedly dead wife, Lenore, but one of the most interesting casting choices in the film is the appearance of a very young Jack Nicholson as Lorre's son, Rexford. Nicholson had worked with Corman before in the original film version of The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), but seeing the three time Oscar winner as a handsome young fellow in tights is an opportunity not to be missed.

Fans of horror-comedy who enjoy The Raven might move on to other examples of the genre, including The Ghostbreakers (1940) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). If Corman's Poe pictures suit your tastes, try House of Usher (1960), Tales of Terror (1962), and The Masque of the Red Death (1964). You'll find Price, Lorre, and Karloff joined by the elegant Basil Rathbone in another delightfully macabre horror-comedy, The Comedy of Terrors (1963), directed by Jacques Tourneur. Richard Matheson, best known today for his often filmed novel, I Am Legend, wrote the screenplays for both The Raven and The Comedy of Terrors.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Vincent Price stars as Dr. Erasmus Craven, a scholarly magician whose nightly studies are interrupted when a large raven seeks admittance to his home. The bird turns out to be Dr. Bedlo (Peter Lorre), another practitioner of the dark arts. Along with their respective offspring, Bedlo and Craven make a journey to the castle of a rival sorcerer, Dr. Scarabus (Boris Karloff), where the magicians enter into a deadly contest of supernatural skill.

While the stars of the film are some of horror's most prolific masters, The Raven relies primarily on comedy for its effect. The performers all seem to be having a good time, although Peter Lorre's hangdog looks and hilarious dialogue make him a real scene-stealer. Any viewer with an affection for Price, Lorre, and Karloff will enjoy this romp, although it's best to come at the picture with an expectation of campy pleasures rather than credible thrills. Scream queen Hazel Court plays Craven's supposedly dead wife, Lenore, but one of the most interesting casting choices in the film is the appearance of a very young Jack Nicholson as Lorre's son, Rexford. Nicholson had worked with Corman before in the original film version of The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), but seeing the three time Oscar winner as a handsome young fellow in tights is an opportunity not to be missed.

Fans of horror-comedy who enjoy The Raven might move on to other examples of the genre, including The Ghostbreakers (1940) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). If Corman's Poe pictures suit your tastes, try House of Usher (1960), Tales of Terror (1962), and The Masque of the Red Death (1964). You'll find Price, Lorre, and Karloff joined by the elegant Basil Rathbone in another delightfully macabre horror-comedy, The Comedy of Terrors (1963), directed by Jacques Tourneur. Richard Matheson, best known today for his often filmed novel, I Am Legend, wrote the screenplays for both The Raven and The Comedy of Terrors.

An earlier version of this review originally appeared on Examiner.com. The author retains all rights to this content.

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Classic Films in Focus: MAD LOVE (1935)

Also known as The Hands of Orlac, Mad Love (1935) offers an unusually literate and even lyrical take on the mad doctor motif, a staple of the classic horror genre. This MGM production from director Karl Freund features well-known horror stars like Peter Lorre and Colin Clive in the leading roles, and it retains its creepy charms thanks to their performances and a number of startling flourishes that modern viewers will still find unsettling more than 75 years after the film's original release. Mad Love is an especially good place to enjoy the peculiar talents of genre icon Peter Lorre, here cast as a strangely sympathetic monster whose worst actions stem from passionate but unrequited love.

Lorre plays the brilliant but unhinged surgeon Dr. Gogol, who spends his days curing lame children and his evenings obsessing over the beautiful actress, Yvonne (Frances Drake). When Yvonne's pianist husband, Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive), loses his hands in a train wreck, Gogol secretly replaces them with the hands of Rollo (Edward Brophy), a knife-throwing murderer recently sent to the guillotine. Stephen soon becomes disturbed by his hands' predilection for hurling sharp objects, while Gogol hatches a plan to drive Stephen mad in order to claim Yvonne for himself.

In addition to his bald head and unnerving expression, Dr. Gogol possesses a curiously poetic soul. He seizes upon a wax figure of Yvonne as his personal Galatea, hoping that his love for the original will make him another Pygmalion. Later, having decided with Oscar Wilde that "each man kills the thing he loves," Gogol tries to strangle Yvonne with her own hair while reciting "Porphyria's Lover," the Robert Browning poem about a similarly homicidal lover. The literary connections underline Gogol's dual identity as a man who might give life or take it away. We see these opposing sides of him in various scenes throughout the film, as he operates on crippled children but also compulsively attends executions. Because he has the capacity to do good and appreciate beauty, Gogol demands our sympathy even as we recoil from his madness. He evokes the same conflicted response in Yvonne, a dangerous reaction given its results.

Colin Clive might seem an odd choice for the romantic lead, for he is not at all handsome, but there's great poetic justice in having the former Dr. Frankenstein fitted with a dead man's hands. The dead man, Rollo, is himself a character from Tod Browning's 1932 film, Freaks, with Edward Brophy reprising the role. Frances Drake makes a lovely heroine, especially in her costume from the theater of horrors where she performs, although some of her transitions with the wax figure can be jarring.

Don't miss the scene in which Gogol impersonates a resurrected Rollo, definitely one of Lorre's scariest and most hysterical performance highlights. Karl Freund is best remembered today as the director of The Mummy (1932). For more of Peter Lorre's villains, see M (1931), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), and The Maltese Falcon (1941). Colin Clive plays Dr. Frankenstein in both the 1931 film and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), but you'll also find him in Christopher Strong (1933) and Jane Eyre (1934).

Lorre plays the brilliant but unhinged surgeon Dr. Gogol, who spends his days curing lame children and his evenings obsessing over the beautiful actress, Yvonne (Frances Drake). When Yvonne's pianist husband, Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive), loses his hands in a train wreck, Gogol secretly replaces them with the hands of Rollo (Edward Brophy), a knife-throwing murderer recently sent to the guillotine. Stephen soon becomes disturbed by his hands' predilection for hurling sharp objects, while Gogol hatches a plan to drive Stephen mad in order to claim Yvonne for himself.

In addition to his bald head and unnerving expression, Dr. Gogol possesses a curiously poetic soul. He seizes upon a wax figure of Yvonne as his personal Galatea, hoping that his love for the original will make him another Pygmalion. Later, having decided with Oscar Wilde that "each man kills the thing he loves," Gogol tries to strangle Yvonne with her own hair while reciting "Porphyria's Lover," the Robert Browning poem about a similarly homicidal lover. The literary connections underline Gogol's dual identity as a man who might give life or take it away. We see these opposing sides of him in various scenes throughout the film, as he operates on crippled children but also compulsively attends executions. Because he has the capacity to do good and appreciate beauty, Gogol demands our sympathy even as we recoil from his madness. He evokes the same conflicted response in Yvonne, a dangerous reaction given its results.

Colin Clive might seem an odd choice for the romantic lead, for he is not at all handsome, but there's great poetic justice in having the former Dr. Frankenstein fitted with a dead man's hands. The dead man, Rollo, is himself a character from Tod Browning's 1932 film, Freaks, with Edward Brophy reprising the role. Frances Drake makes a lovely heroine, especially in her costume from the theater of horrors where she performs, although some of her transitions with the wax figure can be jarring.

Don't miss the scene in which Gogol impersonates a resurrected Rollo, definitely one of Lorre's scariest and most hysterical performance highlights. Karl Freund is best remembered today as the director of The Mummy (1932). For more of Peter Lorre's villains, see M (1931), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), and The Maltese Falcon (1941). Colin Clive plays Dr. Frankenstein in both the 1931 film and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), but you'll also find him in Christopher Strong (1933) and Jane Eyre (1934).

Classic Films in Focus: THE DEVIL-DOLL (1936)